WGBH announced the end of “Basic Black” as a TV production in May along with “Greater Boston” and “Talking Politics.” Layoffs claimed 31 positions.

For some with experience inside Boston’s only public television station, the end was expected. WGBH’s commitment to local programs, they say, has been in retreat for decades.

A community committee charged with defending the longest running public TV show for Blacks was allowed to lapse. WGBH’s records of the group ended in 1993.

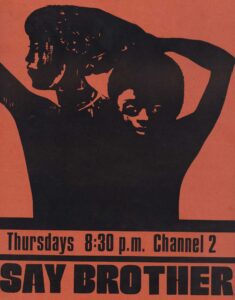

Originally called “Say Brother,” it often presented a counterpoint to the consensus. For most of its 56-year run, that eccentricity was a strength.

But during its “Basic Black” era, the show’s creative energy was replaced by a staid in-studio format. Without funds for camera crews, creating film or artistic inspiration, the production reverted to a common public affairs template: talking heads.

“Say Brother” was born of turmoil, for Barbara Barrow-Murray. “The country was already troubled” by the Vietnam War, she said. After Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in April 1968, a movement made gains. Broadcast, she said, was “just one element.”

“‘Say Brother’ came in with a roar,” the long-time producer explained. During her tenure, the community committee preserved that intensity.

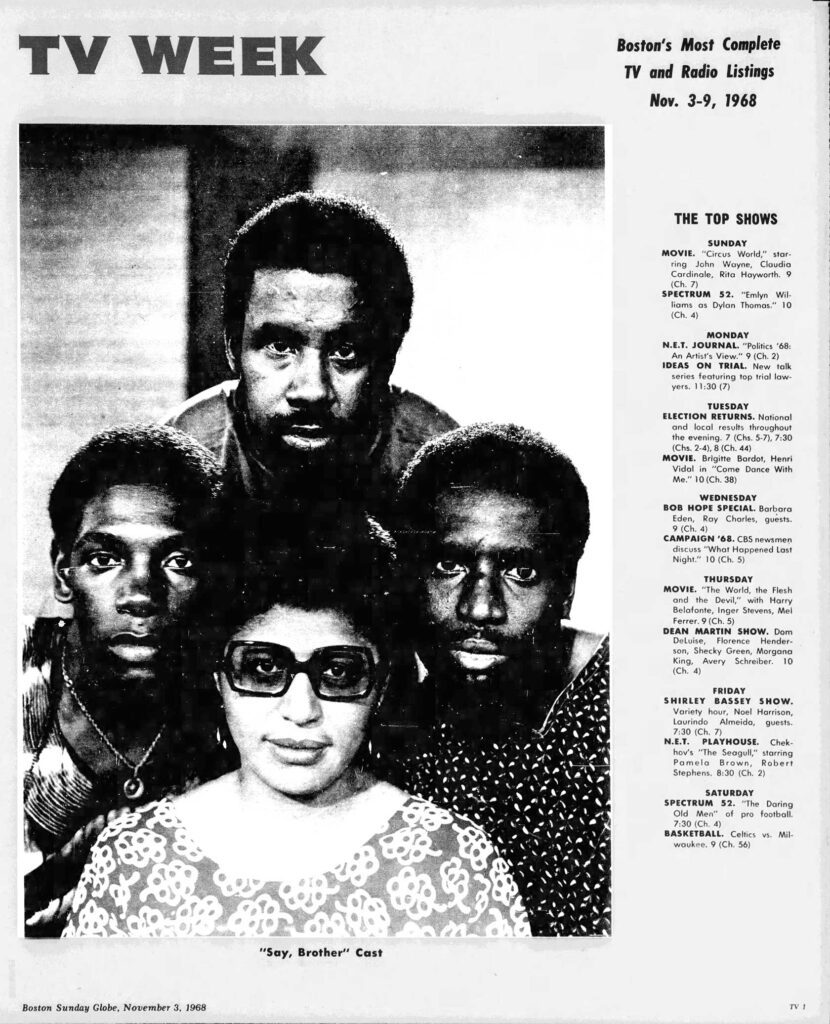

Juanita Anderson, the series producer from 1988 to 1993, said struggles for representation in media preceded Dr. King’s slaying. After, a national ecosystem of Black TV began with “Detroit Black Journal,” “Black Horizons” and “Say Brother.”

Next, said Marita Rivero, “came the New York Public television station with Black Journal and Soul Train.” Rivero produced the show starting in 1974. She continued, “Black people were really demanding space everywhere.”

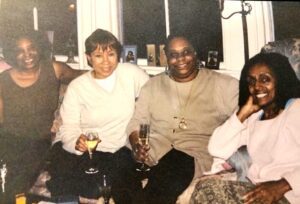

Say Brother Alumna, Beth DuVal Deare, Tanya Hart, Barbara Barrow Murray and Salem Mekuria. PHOTO: Courtesy of Barbara Barrow-Murray

These early programs expressed the complexity of Blackness in America at the time through variation. Art was an essential tool of self-representation.

Tanya Hart started on “Say Brother” around 1973. At the time, she said, “Black people were very hopeful.” Hart was the show’scorrespondent.

Even after the 1960s, “we were hopeful that this country would pay off on the promise that we knew it could be.” She urged us to remember “folks were really trying to tear Black folks down. They had just killed our leader.”

Without bitterness, Black Americans helped heal the wounds in our culture. “‘Say Brother’ helped America get to the point where it could fulfill its promise.”

The show almost ended in 1970 because “it went down to New Bedford with a film crew” and covered unrest, Rivero said. Airing “one of those seven words that the FCC does not allow,” it was put off the air.

The Community Committee to Save “Say Brother” was formed in 1970. WGBH filed its agreement, called guidelines, with the FCC in 1971.

Anderson described the community committee as a form of insurance, guaranteeing that “Say Brother” could continue as a television series.

In the mid-70s, “Pan-Africanism” was popular alongside post-Colonial independence efforts. Rivero said, “Say Brother” coincided with the Black Arts Movement. “Poets, dancers, performers of all kinds, writers, had our attention.”

Even though “Say Brother” had a small studio, they found ways to feature art, she said. “You could bring slides and film pieces.”

By the 1980s, a crack-cocaine infusion in Black communities undercut the sense of hope. “The powers that be start stomping you down again,” Hart said.

As the show’s art critic, Hart brought viewers into the basements of Boston’s major museums, revealing the King Tut mummy before it was exhibited publicly.

“That was the beauty of television: we provided visibility,” said Hart, to people and events that would have otherwise gone unnoticed.

“The caliber of people working at ‘Say Brother’ always remained high,” said Rivero. The resumes of young people were distinguished for having experience at WGBH.

“Say Brother’s” variety format continued for its first few decades. News, entertainment and culture formed an engaging combination.

Barrow-Murray said, “To learn a people, you need to understand their culture…. Everything is demonstrated about our lives in the arts.”

Elma Lewis’s arts programs earned attention through “Say Brother’s” airtime. When her program was threatened, she had a platform to speak out.

“There was a lot of Black talent in that town,” said Hart of Boston. “‘Say Brother’ was a great training ground,” she continued. “We always had the state-of-the-art equipment to work with.”

Carl O’Neal, a “Say Brother” producer, said WGBH had once been proud to put on the show. He traced the evolution of its format from one that informed, educated and entertained to “just basically a talk show.” The talk show format limited viewership, he said. “It just wasn’t given no love.”

For O’Neal, the decline began in the ‘90s, even though that decade hit high notes like Nelson Mandela’s visit to Boston and a film crew traveling to South Africa on the eve of his election.

Calvin Lindsay, another series producer from 1988 through 1993, said “Say Brother’s” community committee was “waning” a bit by the end of his tenure. He said the inevitable end of “Say Brother’s” TV-run was obvious from before he took over the show.

Lindsay recalled being asked to contort storylines to other perspectives, which he didn’t mind. But he felt his reasonable replies to such “editorial policing” should have been respected.

“We devoted a tremendous amount of coverage to Nelson Mandela’s visit” to Boston in June 1990, said Anderson. She was the series producer from 1988 through 1993. Never once was she provided a series budget.

“Say Brother” camera crews often recorded interviews other stations couldn’t, since the community knew their words wouldn’t be twisted. Lindsay said “Say Brother’s” skepticism was essential during the Carol Stuart murder investigation in Boston. He credited fearless reporters like Lovell Dyett and Elliot Francis for fighting to get good stories.

Through the early 2000s, Anderson said that the digital transformation weighed heavily on public media budgets.

O’Neal said, “Say Brother” and “Basic Black” eventually became a way for WGBH to get their FCC license. “We were always treated like second-class citizens there.” Instead of resources and commitment, he recalled cuts to everything from engineers to studio time.

Especially without the community committee, the show lost its accountability to local Black leaders. Empowered by a formal agreement, they had been able to argue “this is what you have to do. You have to honor it,” said Barrow-Murray.

“The FCC used to be concerned when it awarded licenses that the station promised to operate for the benefit of the community,” said Carmen Fields, a former WGBH host.

“Public media is designed to service our communities and we are the public. We are a vital part of this public,” said Anderson. When she started in public media, “the notion that you had the community in your coverage area” was explicit. Since then, she said, the language has changed.

Community issues covered on air are reported to the FCC quarterly. WGBH’s last filing exclusively cited national programming.

WGBH plans for a digital reboot. Rivero said the risk is losing the Black voice entirely. She said Black twitter showed that such a voice could survive online.

Anderson emphasized that incarcerated people are often reliant on public media, given the limits on their digital access and what television is allowed in prisons. She said the success of “Basic Black’s” digital reboot would be a factor of resources.

WGBH, said Barrow-Murray, “were the forefathers of” Black TV programming. She recommended they “recapture what they contributed in the first place.”

Hart was adamant that the “Say Brother” archive should be preserved as “the last bastion of early Black television history.” She argued, “everybody else is trying to wipe our history out.”

Sherylle Linton Jones worked on the show in the early 1990s. She credited “Say Brother” with heralding the organizers and activists who came before. She teared up talking about her colleagues’ efforts on “Say Brother.” Her own recollection was emotional too, “it was my life.”