Even from a distance, one painting stood out among the many iconic works on display at the 2015 reopening of Harvard Art Museums. In this supersized portrait, an artist with a towering Afro and a mask-like, ebony face gazes at the viewer from behind an enormous, multicolored artist’s palette that resembles a warrior’s shield. He holds his paintbrush like a royal scepter and dips it into a dollop of black pigment.

The 6-by-5-foot work, “Untitled (Painter)” 2008, is now among the 80 works by African-American artist Kerry James Marshall in a sensational retrospective on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City through Jan. 29. Spanning the artist’s 35-year career, the show fills 15 galleries on two floors at the Met Breuer on Madison Ave.

Entitled “Kerry James Marshall: Mastry,” the exhibition debuted at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, not far from the city’s South Side, where the artist has lived and worked since the late 1980s. The show will move in spring to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), 10 miles from Watts and the public housing project where Marshall and his family lived when they moved from Birmingham, Alabama.

All three museums organized the show. The editor of its superb catalog, which includes writings by Marshall, was MOCA’s chief curator, Helen Molesworth, formerly a curator at both Harvard and the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston.

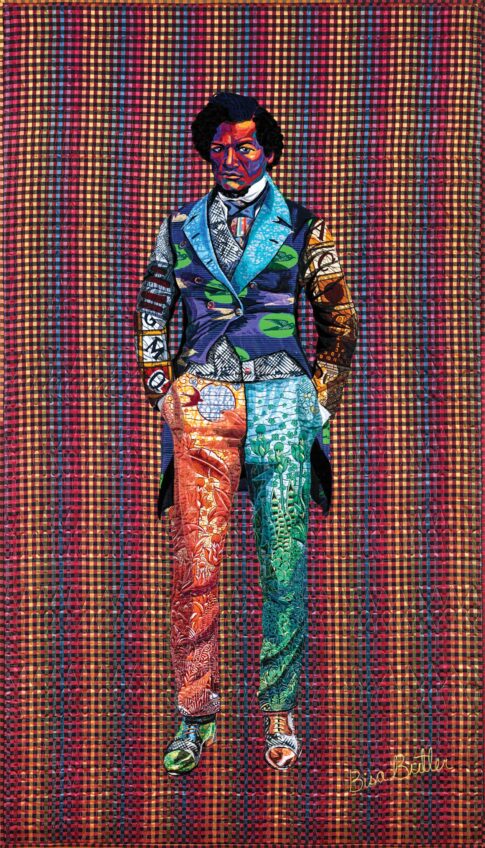

The word “Mastry” in the show’s title hints at slavery, southern slang, and mastery — the career-long aspiration of Marshall to summon the traditions and techniques of the Old Masters and render the black figure with prominence in the canon of Western painting. His mission has been to fill what he calls the “vacuum in the image bank” and correct the absence of black people as artists, audiences and subjects. His works rewrite both art history and social history.

“Things that we see actually do matter,” the artist said at the Met Breuer opening in late October, noting that images enable people “to imagine the world in the fullness of possibilities.”

Instead of depicting African Americans in scenes of trauma and violence, Marshall’s paintings tell stories of people living ordinary good lives. Some of his subjects, like the male and female artists he portrays in one series, also aspire to mastery, which he regards as a lifelong pursuit.

A recipient of a 1997 MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant, Marshall, 61, holds a BFA and honorary doctorate from the Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles. For many years, he was on the faculty of the School of Art and Design at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Early on, he embraced narrative painting instead of more fashionable trends such as concept-laden installations. He acquired a deep knowledge of western narrative painting traditions from the 16th century to the current day. Drawing on this knowledge, he quotes iconic images, not unlike a like jazz musician who riffs on a revered line and claims a place in a hallowed tradition by reinventing it.

Marshall often works in series that replicate the genres of Old Masters — history paintings, landscapes, romantic vignettes and portraiture — and populates his paintings almost entirely with black figures.

His subjects lack the varied hues natural to human faces of any race. Instead, their skin is deeply black. Using old school techniques, Marshall makes black pigments by grinding them out of ivory, tar and iron oxide.

“Extreme blackness plus grace equals power,” he says, in a 1999 interview quoted in the catalog.

Inspired by Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel, “Invisible Man,” the earliest painting in the show is a tiny study in black and white entitled “A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self” (1980). Executed in egg tempera, the jaunty, rough-hewn image shows a man’s face and fedora, black except for his eyes, gap-tooth grin and shirt collar.

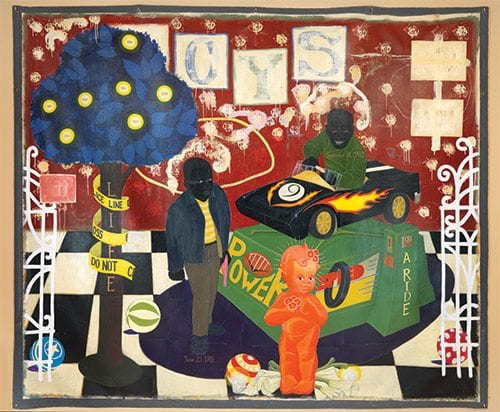

His paintings have since evolved in style and materials and expanded greatly in scale. Like the figures in Byzantine icons, Marshall’s subjects have become streamlined, elegant compositions of curves with sculpted facial features and bodies. Many paintings layer acrylic paint, glitter and other collaged materials on surfaces of unstretched canvas that exceed 8 feet by 10 feet.

These works include the monumental paintings on display at the entrance of the exhibition. Marshall’s memorial to children slain by gun violence, “The Lost Boys” (2003), juxtaposes such boyhood joys as a racing car and basketballs with a bullet-laden tree and the figures of two victims, one holding a toy gun.

Next to it, “De Style” (2003) turns the scene of a busy barbershop into a group portrait that evokes Old Master paintings of nobles posing for posterity. With its title, Marshall proclaims his riff on the Dutch modern art movement De Stijl and works in some signature elements of one of its stars, Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) — a red, yellow and blue palette and geometric grid.

A female version, even larger in size, is on display in another gallery. “School of Beauty, School of Culture” (2012) presents the patrons and staff of a hair salon as equal in grandeur to the ladies of the Spanish royal court immortalized by Diego Velazquez in his 17th century masterpiece “Las Meninas.” Like Velazquez, Marshall inserts himself into the scene, casting himself as a figure almost obscured by his flashing camera. Outfitted in exuberant urban fashions and crowns of ornate hair, Marshall’s royal ladies strike poses while a toddler looks with curiosity at the vanishing apparition of Sleeping Beauty, an ideal fading into thin air.

Marshall’s genre paintings include seaside idylls showing black families at leisure and landscapes that turn urban public housing towers and suburban neighborhoods into pastoral scenes inhabited by children at play and young people busy gardening and tending their yards. He portrays boys and girls in Boy Scout and Campfire Girl uniforms, and festoons images of young lovers with lines from R&B hits, hearts and bluebirds.

His paintings also give space to grief. In “Souvenir 1” (1997), a grandmotherly figure with gilded angel’s wings tends the treasures in her parlor, which include a poster honoring the Kennedys and Martin Luther King. Above it, the faces of other civil rights martyrs float like cherubim.

Marshall’s aspiration to reinvent the portrayal of black life extends to pop culture. Since 1999, he has been developing an action comic series, “Rhythm Mastr,” slated to become a graphic novel and animated film. A light box display shows prints from the series, which follows an athletic and articulate squad of teenagers as they fight crime in Chicago.

At the Met, the retrospective includes a companion exhibition of Marshall’s selections from the museum’s collections. Among the 40 works are power objects from West Africa, Japanese woodblock prints of warriors — kin to his teenage crime-fighting squad, and images by mid-century African American artists, his fellow trailblazers.

Marshall’s commanding portraits of male and female artists celebrate trailblazers to come, and each figure regards the viewer with the steady, unflinching gaze of inner power.