When politicians fail, sometimes artists succeed.

Last month, when Colombians by a narrow margin vetoed a peace agreement to end their country’s 52-year civil war, artist Doris Salcedo drew thousands of citizens to a square in the center of the nation’s capital, Bogotá. Together, they wrote the names of war victims on acres of white fabric in a vigil that gave voice to the healing yet to come.

Salcedo’s sculptures, installations and public interventions give voice to victims of violence, from the tortured and slain in her own country to mothers in Chicago housing projects whose children were killed in gun violence.

“All art is political,” Salcedo, 58, said while in Cambridge to open an exhibition of her works at the Harvard Art Museums. “The expression ‘political art’ is redundant.”

In the wake of our own bruising election, it seems worth noting that the word “political” means power in a public sphere. In her works, Salcedo counters the annihilating force of political violence, which often mutes its victims, by making loss visible and evoking empathy across time and place.

Suffering presence

As a sculptor, Salcedo transforms matter into something beyond itself. With an alchemist’s drive, Salcedo pushes her chosen material to achieve what she describes as “the impossible:” an encounter with what has been lost and a requiem that the victim was denied by his or her assailant.

Instead of depicting individuals or events, her semi-abstract sculptures engage the viewer in reflection and remembrance. With poetic power, they conjure associations and memories in the viewer, who becomes an active participant in her work.

The strenuousness of Salcedo’s process, itself a ritual of mourning, begins with interviewing survivors and extends to exhaustive research into materials, often in collaboration with scientists.

An artist of international renown, Salcedo was awarded the Nasher Sculpture Center’s inaugural Nasher Prize in 2016 and also received the 2014 Hiroshima Art Prize.

Her influences include Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), a Luftwaffe pilot in World War II who after being shot down reinvented himself. As a sculptor, performer and teacher he probed the soul of post-war Germany and influenced many younger artists to do the same on their own turf.

Here at Harvard (and formerly MIT), Salcedo’s fellow Hiroshima Art Prize recipient, Krzysztof Wodiczko, expresses the suffering of marginalized communities through video projections on civic buildings. His 1998 installation commissioned by the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston screened videos on the Bunker Hill Monument of grieving parents as they broke their silence about gun violence in Charlestown.

Loss and change

On view through April 9, 2017, the spare and intense exhibition entitled “The Materiality of Mourning” and its catalog by the same name culminate a decade of research by the curator, Mary Schneider Enriquez, the museum’s Houghton Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art. Her catalog explores Salcedo’s work from the 1980s to the present, and includes essays by the artist and the museum’s conservation scientist, Narayan Khandekar, who writes about Salcedo’s use of fragile organic materials and the challenges of conserving her works.

The four galleries show nine works from 2001 to 2016 that progress from sculptures of great size and weight to ephemeral objects that appear as light as air.

In the first gallery, two hulking rectangular structures are on display. Viewed from the entrance, they interlock into an abstract composition that is a visualization of silence. The chalky white surface of one reflects the gallery’s pale grey light. Yet close up, the structures show signs of a history. Panels of fine burled wood in a warm, burnished tone and here and there, crown molding, reveal parts of an armoire and a slab that once topped a dining table. Yet this furniture has been rendered dysfunctional — taken apart, reassembled at jarring angles and sealed with concrete, a touch that adds a devastating note of permanence. They can never be restored to their former use, just as the life of their original owner is changed forever. A sense of gravity and dignity prevails as well as loss.

Terrible beauty

In the next gallery is an assembly of backless, skeletal chairs arranged in several loosely linear groups. Salcedo made a wax model of a wooden chair and fashioned these replicas in stainless steel, which she then hand-carved with cracks, dents and tears to evoke absence and violence.

This stark metallic installation remains partly visible as a viewer contemplates the works in two adjoining galleries, which in contrast, appear to be objects of fluid delicacy.

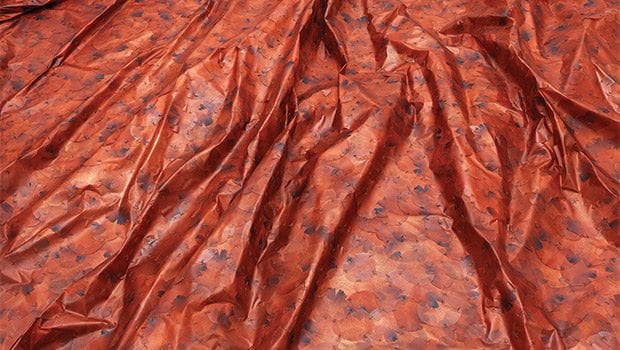

In one gallery, a tapestry is spread across the floor. Arranged at an angle, its puckered folds suggest a wave washing up on sand. Its burgundy and brown surface has a sheen, and close up, brims with organic life. The source of its rich earth tones is its material: thousands of red rose petals, hand-sutured to a fabric backing. Although Salcedo treated the petals to prevent withering, their slightly blackened imprints suggest a touch of decay. This effect increases the poignancy of the work, entitled “A flor de Piel” (2013). Striving to render the paradox of irretrievable loss and remembrance within the very fabric of her sculpture, Salcedo imagines her tapestry as a shroud for a nurse tortured to death in the Colombian war.

Four shimmering blouses hover like wraiths along the walls of the next gallery. Attached by hidden supports, they appear to float and cast diaphanous shadows. On close inspection, the material that glistens in these hand-woven pieces becomes visible: thousands of tiny needles. Salcedo composed these sculptures, part of a series she entitled “Disremembered” (2014-16), after visiting mothers in Chicago housing projects who had lost children to gun violence. Seen from a distance, they are objects of beauty. But they can inflict pain, like a penitent’s hair shirt—or a mother’s grief.