Body camera hearing leaves questions

Attendees raise concerns over BPD’s stance, program timelines

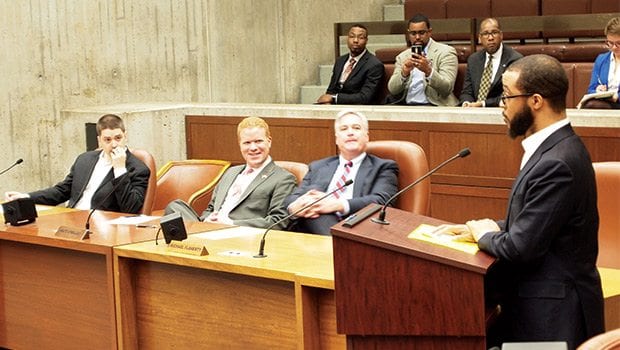

The first hearing on the anticipated police body camera pilot program was held last week, convened by City Councilor Andrea Campbell, chair of the Committee Public Safety and Criminal Justice. It followed on three evening community meetings held during the previous week, and some anticipated this would be a chance for a deeper dive into the issue.

Call for details

The hearing — like the prior Monday’s community meeting — largely served as an open forum for attendees to present councilors with concerns and questions. But regular advocates in the body camera debate seemed itching to move discussion forward.

“There are many model policies that exist,” said Carl Williams, staff attorney of the ACLU of Massachusetts. “Many — if not every single one — of the questions that have been raised in forum are answered in the policies.”

Both Williams and Segun Idowu, co-founder of the Boston Police Camera Action Team, urged councilors not to reinvent the wheel and said that discussing specific proposed policy items would make for a more productive and grounded meeting. For instance, Williams suggested, councilors could focus discussion by soliciting feedback on whether footage should be retained for three months, nine months, or another period of time and what concerns residents have about the different options. Shorter storage times are less costly, while longer ones allow for reviewing incidents further in the past.

Campbell, however, is following a different timeline than the ACLU and BPCAT, which presented their jointly-drafted policy before the city council in August 2015. Campbell said she is still in the stage of gathering community feedback so as to better inform pilot program policy development. Drafting and presenting the proposed policy for public comment will be stage two of the process.

Campbell said the committee will continue to solicit more community voices.

“The intention behind the community meetings was get more of those voices and make sure they, too, were a part of the policy discussions,” Campbell said at the hearing. “We will continue in that regard.”

Her office was not able to tell the Banner how she will determine when she has gathered enough feedback.

The body camera pilot program, initially scheduled to debut this month, has been postponed. Leila Quinn, Campbell’s director of policy and performance, told the Banner that the pilot program definitely will start this summer. She could not confirm that a usage policy will be made public or completed before the pilot begins.

Missing voices

Boston Police Department Commissioner William Evans, along with members of the BPD and members of the Social Justice Task Force originally were expected at the Tuesday hearing. That would have marked the first time Evans has appeared to answer public questions on the pilot. But due to a wake for a BPD officer taking place on the same day, Campbell said she asked BPD and task force members not to attend the hearing.

The absence of key decision makers left some questions lingering.

“We are here in an echo chamber, speaking to ourselves,” Idowu said, adding that the hearing should have been postponed until they could join.

Alex Marthews is the president of Digital 4th, a coalition that advocates for electronic communication privacy and currently promotes a bill for statewide adoption of body cameras. At the hearing, Marthews expressed concerns about Evans’ abilities to impartially structure and assess the pilot.

“Commissioner Evans seems like he’s had to be dragged into this,” Marthews said. “Someone who thinks [body cameras] are really not needed is not going to create a good policy.”

He charged that Evans has exaggerated the difficulty of crafting policy and that the BPD has not been as open in engaging with the community on this as police in other cities have been.

“He’s conveying to the press that this is all terribly complicated … but whether or not he’s willing to think these things out, other people have,” Marthews said.

In April, Evans told the Boston Herald that he did not see body cameras as necessary, a statement that many supporters of such a program took as a red flag.

“I know the momentum is for everyone having them, although I don’t really think we need them,” Evans said. “I think we’ve shown what kind of a class-act department we are, but we are going to give them a try and see if the results are positive.”

Lt. Detective Mike McCarthy, BPD’s director of media relations, said in a statement to the Banner that Evans does not oppose cameras. An independent third party, Anthony Braga, will perform the analysis and interpretation of the pilot, McCarthy added. Braga is a professor of evidence-based criminology at Rutgers University and the soon-to-be director of the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Northeastern University.

“The commissioner has never opposed the program. He has been supportive of it from day one,” McCarthy said, adding that, “The commissioner is confident that Dr. Braga will provide an unbiased review of the program.”

Additionally, McCarthy pointed out that the policy’s development is influenced by the Social Justice Task Force, which comprises six members of BPD command staff, including Evans, as well as 17 community members invited by him. At the hearing, Campbell promised that the names of the task force members will be made public and assured attendees that not all members have the same view point as Evans.

Throughout the hearing, Campbell promised attendees that there will be another hearing this month with the BPD present, although she noted it will have to be fit into a schedule already packed with budget meetings.

Campbell also urged attendees not to criticize Evans for his absence at the prior week’s three community meetings. She said the meetings were not organized by the BPD, but by the Committee on Public Safety and Criminal Justice and the Social Justice Task Force.

Officer benefit

The call for police-worn body cameras originated out of public demand for greater police accountability following the August 2014 fatal shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri by Officer Darren Wilson. At the hearing and community meetings some presented cameras not just as a ward against misconduct but also an asset to all officers.

At the Roslindale community meeting, Jack McDevitt, member of the Social Justice Task Force, said that footage is a valuable training tool. For instance, video of traffic stops can reveal ways that the officers conducting them sometimes put their bodies in front of the car, in danger. And while videos of contested incidents sometimes show officer misconduct, other times footage can also exonerate them.

McCarthy said the police are aware of the value of capturing interactions on film: “We have already seen the benefit of having video footage available for use in training and police community interactions.”

One example, he said, occurred in March 2015 when gang unit officer John Moynihan was shot in the face while conducting a traffic stop. In the ensuing shootout, the suspect was killed. The incident was captured by a nearby business’s surveillance video.

During an April 2015 press conference Suffolk County District Attorney Daniel Conley said releasing the footage to the public helped quash rumors and provide context for the officers’ actions in the shootout.

“In those instances in which video evidence can inform the public as to what happened and why, it is in everyone’s best interest to share that information as soon as possible in order to tamp down speculation and rumors meant to inflame and not to inform,” Conley said.