‘Barbed’: A South African artist confronts the post-Apartheid world

Growing up in apartheid South Africa, artist Jocelyn Chemel was taught to keep quiet. Jail time was an ever-present threat, and as Chemel’s parents searched for an exit strategy, she took in the violence around her in silence. The image that haunts her mind and her work is the tight, menacing coils of the barbed wire that divided the country by race, class and physical distance. Her show “Barbed,” up at the Mayor’s Neighborhood Gallery in City Hall until Sunday, February 28, deals with the injustice she witnessed and the path to a safer tomorrow.

Chemel journeyed back to South Africa in 2013, just after the death of the country’s guiding force, Nelson Mandela.

“It gave me a chance to look at the country through different eyes, post-apartheid,” she says. Chemel was disturbed to find that much of the barbed wire she remembered from her childhood was still present. Though no longer used directly as a divisional system, the wire was on the side of the road, left forgotten in bunches, and littering street corners. The landscape continued to be cut up with the wire, just as it continued to be cut up by social strife.

Author: Photo courtesy Jocelyn Chemel“Yellow Flower,” a digital photograph mounted on wood panel with resin.

“I began to see barbed wire as a symbol of social, racial, and class segregation,” she says, “I want to draw attention to the violence that’s hiding in plain sight.”

Some of Chemel’s images of the wire are stark, aggressive photographs of the rough metal on concrete walls and lining fences. But many others soften the wire in unexpected ways, hiding the cruel history of the material.

“I wanted to evoke a feeling of guilt when you realize what it represents,” says Chemel. “Yellow Flower” is a striking composition on a smoke grey background. Buttercup yellow blossoms wind diagonally down the canvas, wrapped around brown vines. Blooming from the other end of the rectangular image are spirals of grey wire, their usual harsh angles muted by a computer-generated softness. The composition is beautiful, a perfect symmetry of the natural and the manmade. But with time, the image becomes unsettling. The inviting flowers are overshadowed by the violent undertones of the wire.

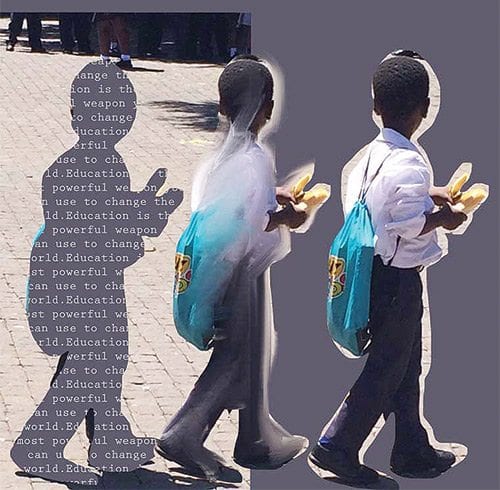

Nelson Mandela is one of Chemel’s greatest personal influences, and she often incorporates him into her work. His call for education as a path to peace resonated with her and inspired “School Boy.” The piece features three children; two are identical cutouts of a photograph, the third is a silhouette with Mandela’s writing running across it. According to Chemel’s website, only one in three children in South Africa is actively educated in school as of 2013. Political and social growth is at a standstill without more educated citizens to get behind it. “‘School Boy’ draws attention to what is still needed [in South Africa],” Chemel says.

Boston has long held ties to Nelson Mandela. In 1990 he came to visit schools in Roxbury, and spoke on the importance of education for young people. Many mayors, including current Mayor Marty Walsh, have cited Mandela as a source of personal inspiration. It seems fitting that an art series partially inspired by Mandela will hang in the walls of the building where change begins.

Despite the tragic source material, “Barbed” has an ultimately uplifting message: There is hope for a brighter future if we are able to educate ourselves and make positive choices. Just as the flowers grow over the barbed wire, bringing life and brightness to a cruel past, we can grow into a more tolerant and inclusive society.