Otis gives notice!

Writer Ginger Adams Otis discusses her book ‘Firefight’

Ginger Adams Otis is a staff writer with the New York Daily News and a longtime reporter in New York City. For more than 10 years, she followed the landmark civil rights discrimination lawsuit brought by a group of black firefighters against the Fire Department of New York. “Firefight: The Century-Long Battle to Integrate New York’s Bravest” dips into the behind-the-scenes struggles inside the city firehouses and inside City Hall as the lawsuit unfolded. It also flashed back to tell the stirring tale of survival of the city’s first black firefighters a century ago.

Did you notice that your book made my annual list of the Top Ten Black Books of the year?

Ginger Adams Otis: I did not! But I am thrilled to hear it. Thank you. It’s always a particular honor to be singled out by someone who is a serious reader.

What interested you in writing about the integration of the FDNY?

GAO: It was a story that I covered closely for more than 10 years and I was always very … intrigued, I suppose you could say, by the wide variety of reactions the lawsuit engendered and the tremendous amount of misinformation that surfaced around it. It’s a battle to get the cold hard facts out there, regardless of how you feel about the suit on its merits. I looked at all the wrong information, misleading information about the suit and the claims made by the black firefighters, and I thought that it was really important to set the record straight, in some way at least.

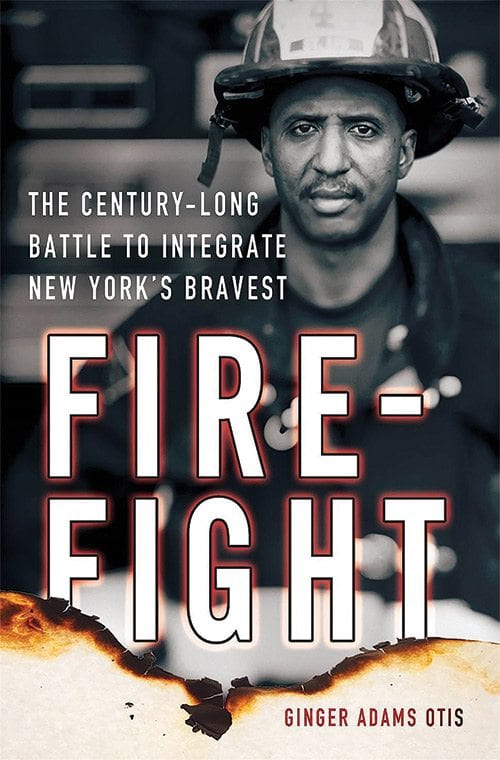

Author: Photo courtesy Amazon“Firefight” by Ginger Adams Otis

Would you describe this project as a labor of love?

GAO: I am not sure it was a labor of love, exactly. … More like a labor of compulsion! It was really hard to pull together all the elements of the story, very challenging to try to bring the people to life and put their arguments and claims in a real-world context. But I couldn’t let it go once I got started — it was like an obsession to get it all out. However, I’d say I definitely fell in love with Wesley Williams’ history. The chapters about the earliest pioneering black firefighters were a joy to research and write.

What was the most surprising thing you learned while researching the book?

GAO: Wow, that’s a good question. I would say that even though I was a reporter covering this topic for years, and though I knew most of the major elements of this story, I was very surprised to learn how many times the city could have solved this problem long before it came to a lawsuit, and yet did not. It’s something I wish I stressed even more in “Firefight,” because the black firefighters still, to this day, take a lot of heat for bringing the lawsuit. In reality, the city could have and should have solved this problem decades ago, but they let opportunity after opportunity go by — and then when it wound up in court, they blamed everyone else. But the chances were there, right in front of them, for a long, long time.

I noticed that you dedicated the book to Captain John Ruffins. Why was that?

GAO: Captain John Ruffins was a New York City firefighter and a Vulcan member, the association of black firefighters who brought the lawsuit against the FDNY. He joined in the 1940s and he was a dedicated and ardent supporter of civil rights, human rights and improving economic opportunities for all the city’s underprivileged communities. He was also an amateur historian and his writing and early research was invaluable for “Firefight.” The most wonderful discovery I made during my journey was a tape recording of an interview he made with Wesley Williams in the 1980s. It’s fascinating to hear Williams describe his own career and I used a lot of it with Captain Ruffins’ blessing in “Firefight.” Sadly, Capt. Ruffins died just before my book went to print and I wanted to dedicate it to him.

How long do you think it would have taken someone else to break the department’s color barrier, if Wesley Williams hadn’t come along in 1919? Did he need to have a special combination of character, skills and force of will, in the same way that Jackie Robinson had when he integrated Major League Baseball?

GAO: Wesley Williams wasn’t actually the first black firefighter in the city – but he was the one that got the most attention and caused the biggest ruckus. Blacks were fighting fires in the city in colonial times, of course. Every able-bodied person — man or woman — had to chip in then, and if you didn’t there were stiff punishments. But as the communal service became more of an actual job — with prestige and community standing, and then later money and benefits – it became for men only. By the late 1800s, when there were about 60,000 blacks in the city, a black man from Virginia joined the FDNY in Brooklyn — at that time Brooklyn was its own department. William Nicholson joined in 1898 and was sent to work in the FDNY’s veterinary unit. Not long after, John Woodson joined in 1912, again in Brooklyn, the product of political maneuvering within Tammany Hall. Neither of their appointments got a lot of attention. But when Williams joined in 1919, two things were different: Brooklyn and Manhattan had become one department and African-Americans were starting their long march toward the Civil Rights movement. Unlike Nicholson and Woodson, Williams’ appointment was a big deal — it was reported in all the papers, especially the black papers. It made huge waves and it was a harbinger of change — and it created tremendous fear, resentment and backlash among the immigrant workforce in the FDNY that was worried about the emerging black workforce.

Why has the FDNY been so much slower to integrate than the city’s other municipal unions?

GAO: It’s a combination of problems. The first being that the FDNY is slow to hire, only once every four or more years. The second problem is that it’s tremendously competitive: upwards of 20,000 to 30,000 people apply for roughly 2,000 to 3,000 positions. And the biggest factor is that within the FDNY, it’s a family job, so for centuries those already on the job encouraged their relatives to apply. Blacks, who were never included in its early years, had a serious stumbling block to overcome just to get a few dozen members on the department.

What is your impression of the Vulcan Society’s decades-long efforts to increase the number of African-Americans in the FDNY?

GAO: Well, it’s tremendously unpopular in many quarters, but it was a legitimate and organized effort to force the city and the FDNY into compliance with local, state and federal civil rights law. The Vulcans were smart, well-organized and ran a stellar grassroots campaign and a lot of people resent them for it, but to my mind, it’s really unfair to blame them for holding the city to task. And they outsmarted a lot of people who drastically underestimated them.

Do you think most people would be surprised to learn how Mayor Bloomberg ignored court orders to increase the number of minorities in the FDNY?

GAO: Oh yes, most people will be very surprised at the actions of all the mayors involved, not just Bloomberg, although he certainly could have done much more to avoid a lawsuit. But it goes all the way back to the Koch era.

How has Mayor Bill De Blasio compared in that regard?

GAO: Mayor de Blasio settled the last remaining leg of the lawsuit within three months of taking office. So, in March 2014, he ended the litigation that had been ongoing since 2007, when Bloomberg forced it to the courts. But change is glacial in the FDNY and it’s not easy to change hearts and minds. There’s a lot more work to be done but it’s coming in small incremental steps.

What message do you want people will take away from the book?

GAO: Knowledge is power. To truly make change, you have to know what your goal is, and have a strategy to get there. Also, institutional racism is hard to see, hard to confront and even harder to explain to the white majority that has benefited from it for so many years. Many don’t see it, don’t want to see it and prefer to hide behind accusations of “special treatment” for people of color.