King and the color line

King’s civil rights struggle broke resistance to black progress, paved way for future success

“The problem of the 20th Century is the problem of the color line.”

W.E.B. DuBois in 1918.

It was 1906 when W.E.B. DuBois posited his idea in a short essay in Colliers Weekly that the color line — the division between people of color and whites — would be the defining issue of the 20th century.

In the ensuing 96 years, other issues left their mark on the century — advances in technology and communications, the civil rights movement, colonialism and decolonization, the rise and fall of communism, the emergence of a global economy.

Yet throughout the century, and into the 21st, the color line remained entrenched — looming over America as this country’s unfinished business.

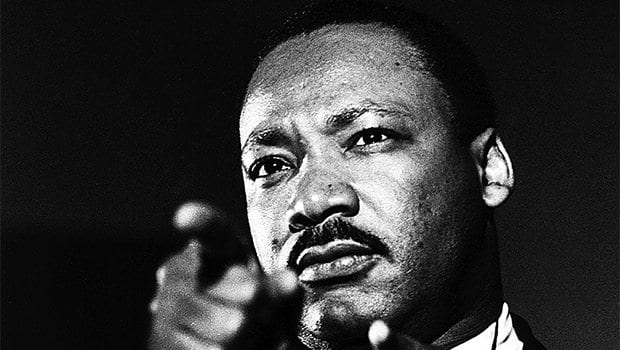

In the middle of the 20th century, one man more than anyone else pricked the conscience of the American people with his call for a colorblind society. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King’s vision of a land where “all men are judged, not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character,” resounded in the ’50s and ’60s, setting the tone for the conscience of the nation.

The fight for equality across racial lines was waged in the courts, the voting booths, lunch counters and schools with King’s non-violent principles serving as the guiding light for the struggle. His rhetoric of a color-blind society was adopted by liberals and conservatives alike in battles over affirmative action and integration of schools, municipal workforces and virtually every area of social interaction.

Race matters

When DuBois first advanced his prediction of the color line, race was the country’s obsession. It was in the waning days of reconstruction, when the Ku Klux Klan rose to prominence and white backlash reared its ugly head. DuBois and other black thinkers saw the gains blacks had won since the abolition of slavery slipping away as Jim Crow became the prominent ethos of the South.

Author: Peter Pettus/Library of Congress. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsA photo of Selma to Montgomery Marches protesters by Peter Pettus.

At the same time, Europe was consolidating its hold on the African continent. India was in the possession of the British, Indochina colonized by the French, and the Western Hemisphere was fast becoming the domain of the United States.

“The tendency of the great nations of the day is territorial, political and economic expansion, but in every case this has brought them in contact with darker peoples, so that we have to-day England, France, Holland, Belgium, Italy, Portugal and the United States in close contact with brown and black peoples and Russia and Australia in contact with the yellow. The older idea was that the whites would eventually displace the native races and inherit their lands, but this idea has been rudely shaken in the increase of American Negroes, the experience of the English in Africa, India and the West Indies, and the development of South America. The problem of expansion, then, simply means world problems of the Color Line.”

In his analysis of the geo-political dimensions of race, DuBois was accurate in his predictions. World War I, according to some historical theories, resulted from Germany’s having been cut out of the division of Africa among European nations. And the Second World War was a result of the first.

While communism played a major role in the wars of the latter half of the century, race was the subtext in many. Take, for instance, France’s loss of Indochina and Algeria, and the resulting bruise to that nation’s standing among its colonizer-equals in Europe.

And America’s ill-fated attempt to keep Vietnam in Western hands met with similar results, and resulted in an even greater loss of life.

In America, color has for most of this century loomed as a major dividing line between the haves and have-nots. Whites dominated blacks, denying them their basic human rights in every facet of life —the color line stood as the major barrier to black advancement.

Dr. King speaks to a crowd.

As King’s life was nearing its end, he found himself in the midst of struggles that appeared to some to stray from the guiding principles of the Civil Rights Movement — advocating vocally against U.S. aggression in Vietnam. Little more than four years after DuBois shed his mortal coil, King was fighting to undo the divisions of colonialism the elder civil rights crusader had warned of.

Occupying the moral high ground in American civic life, King, perhaps more than any single figure in the 20th century, broke open the barriers to black progress. His 1968 assassination gave further impetus to the efforts of the movement to open the doors for blacks. Colleges and universities that previously admitted one or two blacks a year — if any — were suddenly admitting dozens. And black college graduates who in decades past were often relegated to service jobs and manual labor suddenly found the doors to white collar employment increasingly open.

While blacks often

fought long battles for access to municipal and state jobs, they now had the legal backing to break down those barriers, and began to do so.

Perhaps neither DuBois nor King could have predicted the whirlwind of changes that came in the wake of King’s 1968 assassination — the growing anti-war movement that helped put the nail in the coffin of colonial expansion, affirmative action, the expansion of black opportunity, the growth of black political and economic power that led, in this century, to the first black president of the United States.

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964.

A blurred line?

Undeniably the color line of the 21st century is no longer the solid, immutable barrier that for so long kept African Americans living in a permanent second class status. Nobody embodies the newfound opportunity available to blacks more than President Barack Obama, now in the last year of his second term. Indeed, his election prompted some pundits to proclaim that the United States has entered a “post-racial” era.

Yet despite transcendence of the color line, Obama’s time in office has highlighted the intractability of that line. He has suffered through small indignities — like being called a liar by a U.S. representative during a 2009 address from the floor of Congress. Or referred to as a “tar baby” by another Congressman in 2011. While Obama maintained a distance from his hecklers, from the “birthers” who sought to contest his very legitimacy as a U.S. citizen and scores of other indignities, on more than one occasion he used the oval office to highlight the disparate realities of black and white America.

In 2013, he interrupted a press conference to speak about the “not guilty” verdict in the shooting of Trayvon Martin. One simple sentence — “Trayvon Martin could have been me” — underscored the precarious plight all black men face in a nation where they are feared by well-armed whites. And last year, he shared with law enforcement officials gathered in Chicago his own experiences with racial profiling.

As Obama underscored, the color of one’s skin still often matters more than the content of one’s character. And DuBois’ color line, though far less visible, is still woven into the fabric of America.