Editor’s Note

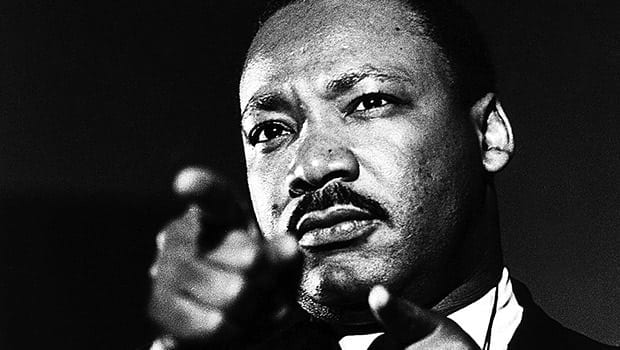

Fifty years ago, Martin Luther King Jr. turned the attention of the Civil Rights Movement to the North. The same year King and other civil rights leaders fought for voting rights in Selma, Alabama, King made high-profile appearances in Boston, New York, Chicago and other northern cities to highlight segregation and inequality. His Boston trip included a march to the Boston Common and an address before the Massachusetts Legislature.

“I want to join … what I consider a very significant struggle,” Martin Luther King Jr., declared on July 7, 1965, after announcing that he and SCLC staffers would spend three days in Chicago later in the month. The news thrilled Chicago civil rights advocates, who looked to King and SCLC to electrify their cause.

“Chicago needs all the help you can possibly give to us to rid ourselves of a system of segregation which throttles the life and growth of the city,” one Chicagoan wrote to King. “[The] people in Chicago,” another insisted, “are elated over the fact that you are coming to help us in our struggle.”

King’s decision to bring his civil rights workers to Chicago for a short visit was not surprising. The civil rights movement was in a state of flux. Even amid its greatest triumphs – the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — the venerable crusader for black freedom, A. Philip Randolph, warned of the dangers of a “crisis of victory.” As the Jim Crow South crumbled, questions followed. Where should the movement go next? What should be its targets? What tactics should be employed?

A new focus

Bayard Rustin, coordinator for the March on Washington and longtime advisor to King, contended that the age of protest was ending, and that civil rights forces should focus on building an expanded coalition of blacks, liberals, trade unionists, and religious groups to enact a sweeping agenda of social democratic legislation.

“What began as a protest movement is being challenged to translate itself into a political movement,” Rustin wrote in an influential essay in early 1965. Yet even as Rustin issued his appeal, SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) and CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality) were turning inward, away from interracialism and nonviolent direct action and toward developing power within black communities. Community organizing had become the watchword among young black activists. Nonetheless, out of this confusion and debate in movement circles a consensus was emerging that more attention had to be paid to the North.

By 1965, SNCC staffers were moving north to begin urban programs, and early the next year CORE targeted Baltimore as the site of a major project to assist inner-city blacks. Only a few years earlier, the notion of southern blacks traveling across the Mason-Dixon line to help northern blacks would have been dismissed as preposterous. Southern blacks had long considered the North something of a sanctuary, a region where black men and women could at least carve out a decent life. Before the Civil War, runaway slaves escaped to the North for freedom. In the twentieth century, hundreds of thousands of blacks migrated North in search of a brighter future. The South — the home of slavery, lynchings, and legalized segregation – had always been the great oppressor of blacks.

Not the promised land

Though a son of the South, King, even early in his career, recognized that the North was not a racial paradise. As a student in Pennsylvania and Boston, he had encountered the sting of northern prejudice firsthand. In one of his earliest speeches during the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955 and 1956, King warned against rosy views on the status of blacks throughout the country: “Let’s not fool ourselves, we are far from the promised land, both North and South,” he told his listeners.

Yet, however injurious northern racial discrimination practices were, in the 1950s and early 1960s they seemed less oppressive than the southern caste system that denied blacks even basic rights of citizenship. In its first years SCLC, founded in 1957 by King and fellow southern ministers, diagnosed the race problem in regional terms: the South was the target, and the North, though no interracial utopia, offered abundant resources that could be tapped to fuel the southern crusade against racial injustice. SCLC could cultivate financial assistance from northern liberals, encourage the federal judiciary to step up its assault on Jim Crow practices, and entice the federal government to intervene on behalf of southern blacks.

King’s diagnosis also highlighted the daily indignities that southern blacks endured under the Jim Crow regime. He sought to end the reign of violence designed to intimidate blacks and to abolish offensive practices such as public segregation on buses, at lunch counters, and in school systems. This was a natural, almost instinctive response. The career of nonviolent direct action after World War II correlates closely with blatant discrimination in public arenas. The first wave of protests struck against segregated northern lunch counters, restaurants, and other public accommodations. As glaring discrimination in public places receded in the North, segregated public facilities in the border states and then in the South became the target of nonviolent direct action.

To King and his followers in the 1950s and early 1960s, the enemy was clear — legalized segregation and discrimination. With the Jim Crow system so palpable and so seemingly intractable and with the assault upon it so consuming, there was little pressure for a more extensive examination of racism in America in civil rights circles. Yet as southern barriers fell and northern unrest mounted, civil rights advocates felt compelled to develop a more sophisticated analysis of America’s race problems, an analysis that doubted whether de facto segregation was generally a natural, rather than a contrived, phenomenon and that detected the blight of institutional racism — inequities grounded into the fabric of American life — everywhere.

Charles Silberman, a respected commentator on American race relations, wrote in 1964: “What we are discovering, in short, is that the United States — all of it, North as well as South, West as well as East — is a racist society in a sense and to a degree that we have refused so far to admit, much less face.”

Redefining racism

King was particularly vulnerable to mounting pressure for a more searching analysis of American racism. The Montgomery bus boycott had catapulted him into the national limelight and despite his focus on the South, he had become a spokesperson for all black Americans. Moreover, the underlying principles behind his civil rights ministry ensured that his social vision was not fixed but eminently expandable. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference might have been a regional organization, but from the beginning its aims reflected its Christian, universalistic spirit. It hoped not just to redeem the soul of the South but, in the words of its founding slogan, “to redeem the soul of America.” King and SCLC were moral voices whose domain could reach far beyond the Mason-Dixon line.

By 1963, King’s public remarks reflected his growing concern over the state of race relations in the North. Like many civil rights activists, he had anticipated that northern blacks “would benefit derivatively” from southern victories. But now, with the tide turning decisively against the Jim Crow South and with the outpouring of northern support for the southern black freedom struggle, he stressed that sympathetic northerners should neither be content with helping southern blacks nor be quietly reaping benefits from the southern struggle. In a series of speeches delivered across the country in the aftermath of SCLC’s Birmingham campaign, King called upon northerners to boost the freedom struggle directly by “getting rid of segregation and discrimination — such as de facto segregation” — in their own communities.

A surge of northern school boycotts in 1964 prompted King to assess further the damage produced by northern racial inequities. With hundreds of thousands of black students in Boston, New York and Chicago refusing to go to school because of alleged unequal education, the depth of northern black alienation could not be denied. King extended his “moral support and deepest sympathy” to the boycotters, commending black parents for “fighting for the deepest needs of grossly deprived children” and “trying to loosen the manacles of the ghetto from the hands of their children.”

Inspired by the northern insurgency, he told an interviewer in May that “while I have been working mainly in the South and my organization is a southern-based organization, more and more I feel that the problem is so national in its scope that will have to do more work in the North than I have in the past.”

Urban riots of ’64

The explosion of urban riots in the summer of 1964 served as the catalyst that drove King and SCLC to work in the North. The violent uprisings struck at the heart of King’s and SCLC’s vision of social change. Nonviolence was more than just a tactic for King – it was a way of life – and SCLC was more committed to nonviolence than any other civil rights organization. King and his SCLC lieutenants felt compelled to offer northern blacks an alternative to violence, and after receiving an emergency call from local ministers, Andrew Young and James Bevel led a team of seven organizers to riot-torn Rochester, New York. Drawing on their celebrity status and wearing overalls, the civil rights veterans reached out to disgruntled and disaffected blacks, stressing that violence would not solve their problems. Young thought the “group had amazing and almost immediate success.”

In the summer of 1964, King even found himself trying to heal northern racial wounds. When a New York City riot — the first major black uprising since 1943 — threatened to spiral out of control, Mayor Robert Wagner pleaded for King to use his influence to help calm the city. Even though the rioting had already subsided, King acceded to Wagner’s request and traveled to the city, where he quickly found himself embroiled in controversy. As King headed to Gracie Mansion to see Wagner, Harlem leaders lambasted him for neglecting them and for allowing himself to be used by the “white power structure.” It would not be the last chilly welcome King would receive as he became more active in the North.

King consulted with Wagner, but he also cooled the tempers of local black leaders by meeting with them and touring New York’s black communities. Although gauging King’s effect on easing tensions is difficult, the episode broadened the Baptist minister’s awareness of ghetto conditions and the depth of inner-city inhabitants’ rage. King warned of future “social disruption [until] the Harlem and racial ghettoes of our nation are destroyed and the Negro is brought into the mainstream of American life.”

The upsurge of northern civil rights protest and the summer rioting prompted King to stress SCLC’s obligation to northern blacks at the organization’s annual convention in the fall of 1964. He did not propose a northern project, but it was clear that northern racial problems would become more prominent in SCLC’s agenda. The bestowal in October 1964 of the Nobel Peace Prize pressed King to widen his social mission even more. “[The prize] was a great tribute, but an even more awesome burden,” Coretta Scott King remarked. King could no longer focus so exclusively on the problems of southern blacks; his arena of reform had to expand.

In his Nobel address King dwelled on the three issues that were to shape the rest of his public career. Before an enthusiastic crowd jammed into a University of Oslo auditorium, King spoke of the necessity of eliminating war and poverty as well as racial injustice from the world.

For the moment, however, King remained focused on southern racism. In February and March 1965, King and SCLC executed their brilliant Selma campaign. Aided by the country’s shock at southern white brutality, they ignited a national demand for voting rights legislation. The Selma campaign would, however, be the last great, heroic episode of the southern civil rights drama. Across the rest of the South, the tide of nonviolent direct action had already passed. A time of debate, confusion, and decision was at hand.

A duty to go north

At a Baltimore strategy session in early April 1965, shortly after the conclusion of the Selma project, King and SCLC hinted that they would soon embark on a new effort. Though the proceedings of King’s proposed boycott of Alabama dominated press coverage, the SCLC executive board took an important institutional step toward broadening the scope of SCLC’s activities by announcing that SCLC would extend its operations into the North. “You can expect us in Baltimore, you can expect us in New York and in Philadelphia and Chicago and Detroit and Los Angeles,” King pledged.

Eight weeks later, after trips to Boston, New York and other cities, King solidified his northern plans. At a meeting in Warrenton, Virginia, in late May, King and his top advisors debated whether SCLC should go north. There was not yet a formal proposal for a specific northern campaign, but some of King’s colleagues, questioning the wisdom of any extended northern thrust, argued that there was still much to be done in the South, that SCLC would find the North unreceptive to its efforts, and that heading north would harm SCLC’s fund raising, which relied heavily on northern contributors.

But King thought otherwise, and he rejected this counsel just as he would subsequent warnings. He felt a duty to go north. He had to reach out to northern blacks. Norman Hill of the Industrial Union Department of the AFL-CIO recalled that after one session in which he and Rustin tried to dissuade King from heading north, King responded less with well-honed arguments for his next move than with the almost unassailable assertion that “this is where our mission is, we have received a calling to come north.”