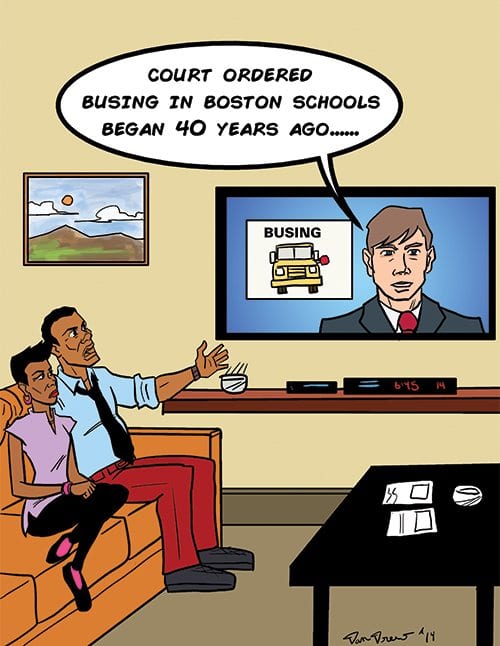

Commitment to racial and religious equality is a difficult concept for people to embrace. In the nation’s Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson wrote “we hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal.” Yet Jefferson relied upon a staff of slaves to run his farm. Although Boston was a major abolitionist center, citizens battled over public school desegregation only 40 years ago.

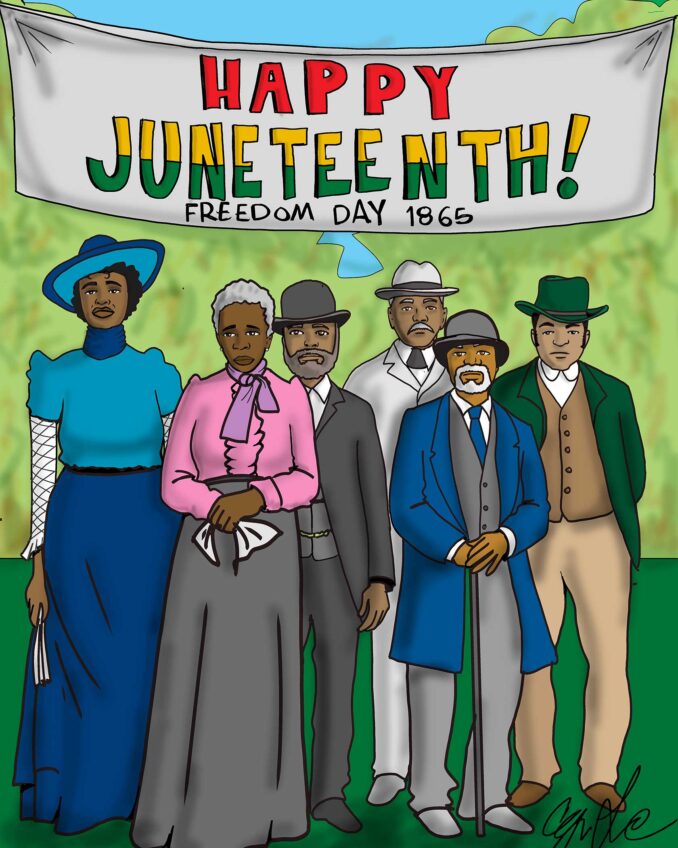

Fortunately, President Abraham Lincoln recognized that slavery was inconsistent with the principle of equality, and ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1865 rendered that practice unconstitutional. However, the elimination of slavery did not take the nation all the way to equality. Segregation was still permissible. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson just 31 years later in 1896 that state-sanctioned segregation was constitutional as long as the facilities were equal.

The concept was that there could be no discrimination in the segregation. The facilities for blacks should be of equal quality to those for whites. This result was readily achieved in the Plessy case which involved segregated railroad cars. Clearly, railroad cars could be indistinguishable from one another except for the race of their occupants.

Not every situation is quite so fungible. Plaintiff’s lawyers in Brown v. Board of Education were able to establish that all classrooms were not identical. They also established that the authority of the state to segregate by race created for blacks a sense of inferiority that could be academically damaging. The 1954 decision in the Brown case made legally imposed school segregation unconstitutional but just as important, it also destroyed the legal foundation for the Plessy case which had been legally effective for 58 years.

The issue of school segregation had been resolved in Boston even before passage of the 13th Amendment. Blacks had established their own schools to avoid mistreatment in the public schools that were open to them. Then Benjamin Roberts challenged the Boston School Committee to provide access of black students to any conveniently located public school. The Boston School Committee rejected the request so Roberts appealed to the Supreme Judicial Court. The case of Sarah C. Roberts v. City of Boston was denied in 1849.

Roberts’ supporters then petitioned the Legislature to reverse that opinion. In Chapter 256 of the laws of 1855, a law was passed that made it a civil offense to exclude any child from public school because of race, color or religion, and it provided damages to prospective students for any violation of the rule.

So the Massachusetts Legislature desegregated the schools 10 years before slavery became unconstitutional everywhere in the nation and almost a century before the decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Again in 1965 the state Legislature passed the Racial Imbalance Act requiring school districts to integrate any school more than 50 percent black or lose state aid for education.

Boston’s public schools had become racially imbalanced by fiat of the school committee. When the committee was unresponsive to the urging to desegregate by blacks in the community, the Boston chapter of the NAACP filed suit on March 14, 1972. The case of Morgan v. Hennigan was eventually won by the plaintiffs on June 21, 1974.

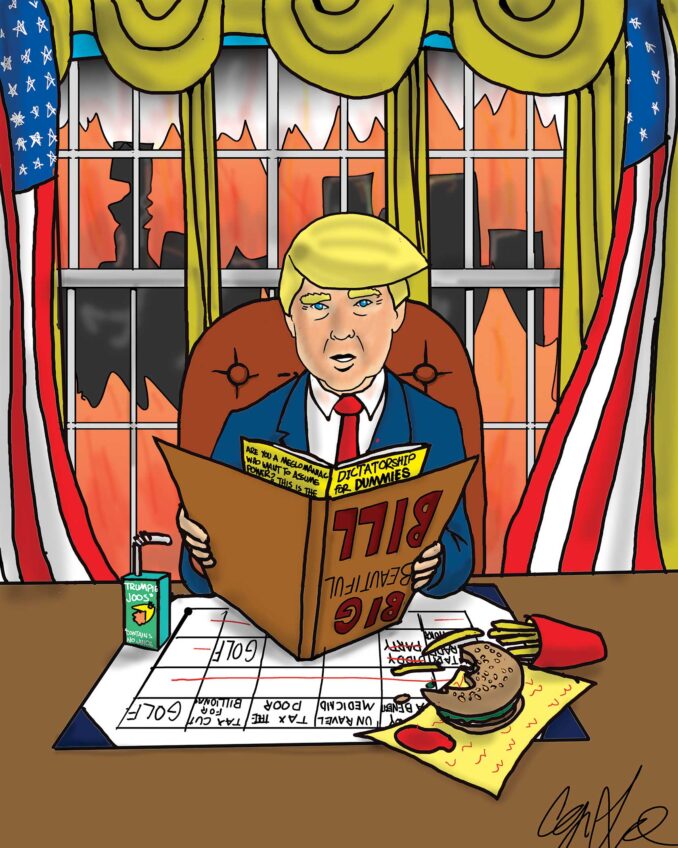

A defiantly hostile school committee refused to accept the court’s decision and cooperate to establish a satisfactory process to comply with the order of the court. Judge W. Arthur Garrity had no choice but to take control of the school system and implement a procedure that did not require the school committee’s support. It was actually white intransigence that created the necessity of imposing busing.

When busing began in 1974, 65 percent of public school students were white, as were 95 percent of teachers and administrators. Black protestors were less concerned about the racial mix in the classrooms as they were about the ethnic identity of teachers and administrators. Blacks demanded integration in the classroom primarily to prevent assignment of black students to deteriorating school buildings while white students went to more modern facilities.

Now, after 40 years of busing, one wonders whether Boston residents have finally matured enough to accept the principal of racial and religious equality.