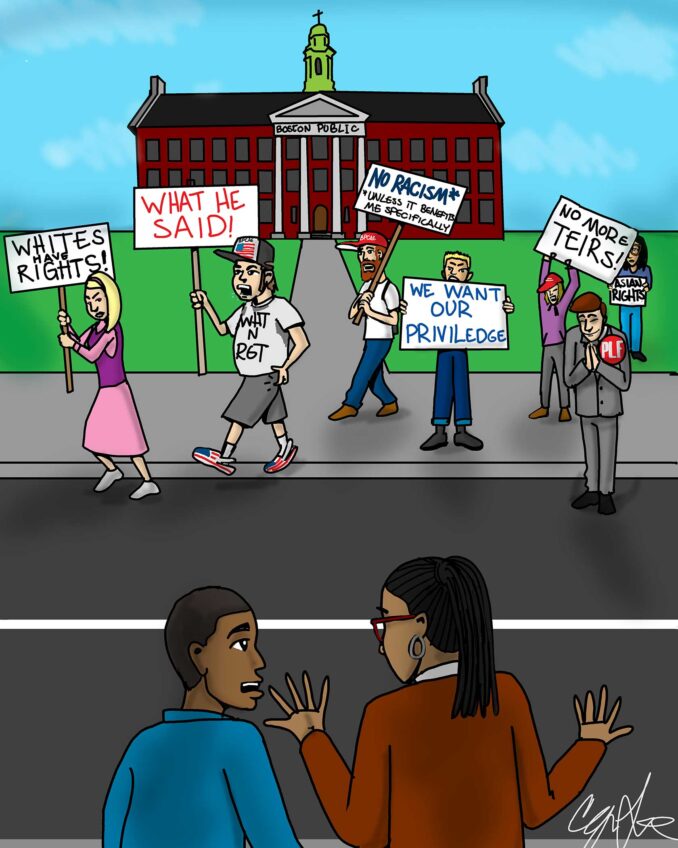

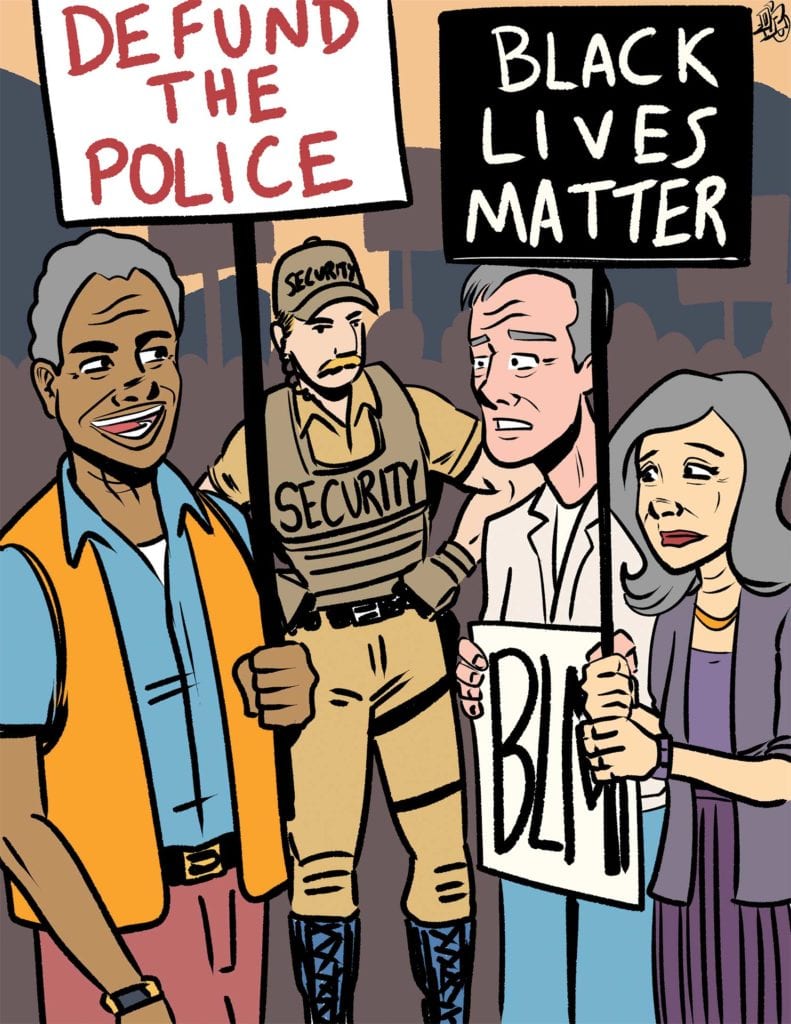

The late John Lewis encouraged everyone to stand up and speak out in opposition to “unchecked, unrestrained violence and government-sanctioned terror.” He called such public reaction “good trouble, necessary trouble.” Indeed, John Lewis followed this standard, and he passively accepted any unjust penalty the bigots might inflict on him, although he was behaving in a manner permitted by the U.S. Constitution and the law.

The Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama has compiled a researched record of 3,959 “racial terror” lynchings that took place in the South from 1877 to 1950. Provocation for such events could be little more than failure to be sufficiently subservient in an encounter with a white person. The protests that Lewis suggest would certainly be sufficient provocation.

The ultimate killing was the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King on April 4, 1968. There had been growing hostility toward him since he began his campaign for justice and equality for blacks with the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955. However, King’s later involvement with the Poor People’s Campaign pushed the racists over the edge. They were unwilling to accept any hazard to their economic livelihood.

The “good trouble, necessary trouble” suggested by John Lewis could ordinarily create great difficulties for the perpetrator. Lewis spent time in Mississippi prisons and had his skull broken by police for participating in protests that every civilized society would find acceptable. Nonetheless, those committed to nonviolence adhere to Dr. King’s principle, “Hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that.”

The perspective was based upon the New Testament injunction “and unto him that smiteth thee on the one cheek offer also the other” (St. Luke, 6:29). Those who do not follow the Bible’s instruction to turn the other cheek would suggest that an adequate physical response might not generate love in the opponent, but it will undoubtedly discourage him from inflicting further pain on others.

Dr. King’s nonviolent approach was influenced by Mohandas Gandhi (1869-1948), a Hindu leader of the nonviolent effort to gain independence of India from Britain. As the leader of the world’s second most populous nation, Gandhi was nonviolent as a useful tactic, not as a religious requirement.

As a practicing Hindu, Gandhi was reliant on the Bhagavad-Gita, which required everyone to recognize his religious duty (Dharma) and be rewarded or penalized in accordance with his success or failure in past lives (Karma). While Gandhi proposed nonviolence for his adherents, he was still ultimately assassinated in 1948 by a Hindu activist who believed that Gandhi had not adequately protected the interests of Hindus in the restructuring of India to create the country of Pakistan in 1947.

Martin Luther King and Mohandas Gandhi, two outstanding adherents of nonviolence, were both assassinated. And unsuccessful attempts were made by the police to include John Lewis in that duo. People must become aware of the risks when they answer Lewis’ call for “good trouble, necessary trouble.” Opponents will not likely be influenced by the agitator turning the other cheek in accordance with Lewis’ views.

American democracy needs citizens who are willing to stand up against oppression and feckless policies, but it is good to remember that there are often those who benefit financially from such programs. Opposition can be very expensive for them, and they will do whatever is necessary to stop it. Be prepared.