America’s battle against obesity

A complicated condition with serious consequences

Kathleen E. Corey, M.D., M.P.H.

Co-Director, Weight Center

Massachusetts General Hospital

When it comes to obesity, nothing is as simple as it seems. A case in point — the recent annual meeting of the American Medical Association (AMA) in which obesity was officially classified as a disease.

Dr. Patrice Harris, a member of the association’s board, said in a statement that the recognition “will help change the way the medical community tackles this complex issue.”

The announcement touched off a flurry of support as well as criticisms. While some believe the measure will spur medical insurers to pay for treatments, others contend that patients might see their weight as something they now have no control over, and reduce their ability to change their diet and exercise patterns.

Even the AMA’s own Council on Science and Public Health voiced their opposition, arguing that obesity should not be considered a disease mainly because the measure usually used to define obesity, the body mass index (BMI), is simplistic and flawed.

“Given the existing limitations of BMI to diagnose obesity in clinical practice, it is unclear that recognizing obesity as a disease, as opposed to a ‘condition’ or ‘disorder,’ will result in improved health outcomes,” the council wrote.

Further complicating the decision to recognize obesity as a disease is that there is not a universally accepted definition of what constitutes a “disease.”

Disease or not, obesity has become a major American problem and on that point everyone is in agreement.

According to the most recent figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), almost 36 percent of U.S. adults and nearly 17 percent of children are classified as obese.

Excessive weight poses a threat to one’s health. Carrying too much fat increases the risk of a myriad of diseases, including high blood pressure and cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke and sleep apnea. It even increases the risk of several cancers, such as colorectal, breast, uterine and prostate.

The medical costs associated with the condition are estimated at $147 billion a year, notes the CDC. The average cost to treat a person with obesity is $1,429 higher than the expense of treating someone of a normal weight. The Surgeon General estimates that 300,000 deaths each year may be related to obesity.

Race plays a factor. A 2012 report in the Journal of the American Medical Association noted that blacks have the highest percentage of obesity at 50 percent followed by Hispanics (40 percent) and whites (34 percent).

Women of color are hit particularly hard. Almost 60 percent of black females aged 20 and above are obese. Add overweight to the mix and the number soars to 82 percent.

The cause of this disparity is probably multi-factorial, but acceptance of and comfort with a wide girth is often touted. A group of researchers found that black women who had obesity consistently reported better quality of life than white women with obesity. Quality of life measures included physical function, self-esteem, sexual life, public distress and work. Black women scored high on the self-esteem scale.

It is understandable, then, that fat is the target of much research. So significant is this issue that a sub-specialty in obesity medicine has been developed by the American Board of Obesity Medicine.

What has been discovered is that, surprisingly, fat is a physiologically complex organ that communicates with other organs, including the brain and the liver. But not all fat is the same and is differentiated by location.

Abdominal, or visceral, fat is centered at and above the waist giving a person an apple shape. Unlike the external fat that can be grasped, visceral fat is internal and lies between the organs in the abdomen. As opposed to fat found in the thighs, for instance, visceral fat is biologically active and can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

As the co-director of the Weight Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Dr. Kathleen Corey knows a thing or two about obesity. She specializes in liver disease and says obesity and the liver are more highly linked than most patients, including some doctors, tend to realize.

The liver is the second largest organ in the body and does yeoman’s work. It produces cholesterol to help carry fats through the body; it clears the blood of drugs and other toxins; and it helps the immune system resist infections.

It also gains weight. As a person accumulates fat, so does the liver. It stands to reason that the rise in BMIs across the country is accompanied by bigger livers.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the buildup of fat in the liver of people who do not drink excessively. NAFLD is common — roughly 20 to 40 percent of the population is affected — and, for the most part, causes no symptoms. It is usually silent and can be missed. “It’s often an incidental find,” explained Corey.

The best treatment for NAFLD is weight loss, exercise and healthy eating. Vitamin E and some medications for diabetes have been helpful, but new medications are in the works. NAFLD is reversible in the early stages.

If not reversed or stabilized, NAFLD can progress to the more serious nonalcoholic steatohepatis (NASH), which can result in cirrhosis of the liver. It is estimated that, with increasing obesity rates, the incidence of a NASH and cirrhosis from NASH will increase.

The connection between liver disease and obesity is one of the reasons Corey agrees with the AMA’s position that obesity is a disease.

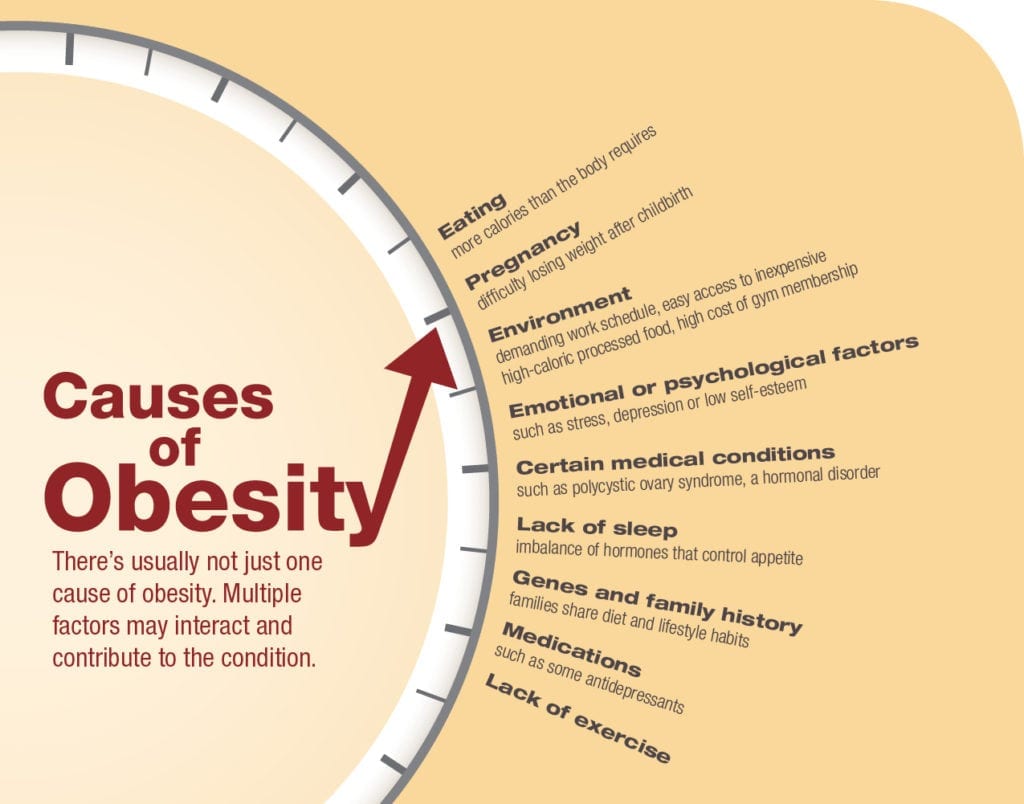

“Obesity is complicated,” she explained. “The cause is multi-factorial. Many people need help to control it.”

She acknowledged that some people with a BMI in the obesity range are healthy. But she said, “We still worry that they are at risk.”

The cause of obesity is pretty straight forward. A person consumes more calories than the body requires. The unused calories are stored as fat. Unfortunately, the body has no limit to adding fat and unburned calories are consistently stored. Furthermore, fat cells cannot be destroyed once formed. A weight loss program will reduce their size, but not the number.

While the cause of overweight and obesity are clear, the reasons they occur are less so. Unhealthy diet and lack of exercise are largely to blame.

But it’s not that simple. Fingers can be pointed in other directions. Medications, such as antidepressants and beta-blockers for the treatment of high blood pressure, are known to cause weight gain. Genetics plays a role as well, as does lack of sleep.

Corey cited many other factors that can lead to obesity, such as an underactive thyroid or emotional disorders.

For people who are trying to lose weight she offers advice. Recognizing that you have obesity and that it has serious medical consequences is the first step. Corey also said that those with the condition must also recognize that they might not be able to do it on their own and may need help.

The treatment for obesity varies and many people rely on several of them. Exercise and healthy eating are foremost. Thirty minutes of daily moderate activity, like walking, are recommended. For those who need more help, three FDA-approved drugs for the treatment of obesity are on the market. Mental health professionals help people find emotional causes of overeating and provide assistance with behavior modification. For those who experience obesity-related medical conditions or difficulty losing weight, bariatric surgery is often recommended.

But more than most, Corey understands the complexities inherent in the battle of the bulge and that chocolate makes people feel so good. She has a simple wish to solve part of the problem. “I wish broccoli would make people feel good,” she said.