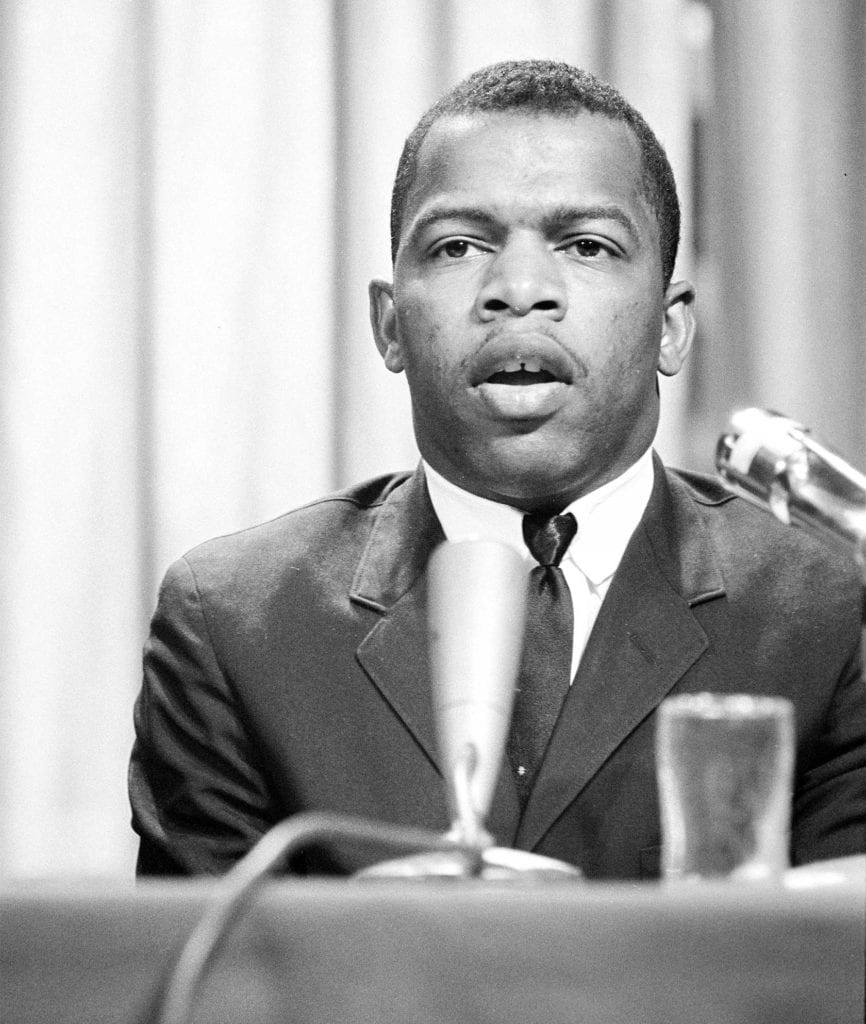

John Lewis, apostle of ‘Beloved Community’

Civil Rights icon crosses his final bridge

John Lewis, the son of a sharecropper who rose to become a giant of the Civil Rights Movement, died July 17 of pancreatic cancer at age 80.

Lewis’ lifetime of struggle and service spanned the early years of protests in the Deep South in favor of voting rights and public accommodations to the front lines of resistance in later years against South African apartheid, police brutality, gun violence, immigrant detention and racism and hate in any form or manifestation.

Lewis endured repeated beatings and jailings in his long career, starting in his early 20s as leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and lasting through over three decades of service in the U.S. House of Representatives as an Atlanta congressman.

Born in segregated Troy, Ala., Lewis aspired early on to the ministry and practiced his preaching skills on curious chickens before taking his message to a global stage. Throughout it all, Lewis never lost his sense of suffering as redemption and the transcendence of forgiveness.

In his memoir “Walking with the Wind,” Lewis wrote that there was “something in the very essence of anguish that is liberating, cleansing, redemptive.”

His principles came under violent tests beneath police batons and truncheons. During a Freedom Ride protest as a Nashville seminary student in 1961, Lewis was left in a pool of blood at a bus station. State troopers cracked his skull during the 1965 march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala.

He was arrested 40 times in the 1960s, five times as a congressman, and, among his many nights behind bars, served close to a month in a notoriously violent Mississippi prison farm.

His selfless advocacy against the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow had an enormous impact on ending legal apartheid in America.

The late John Lewis embraces then-President Barack Obama during a 50th anniversary of a civil rights march on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Alabama. OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO BY PETE SOUZA

Public reactions to the institutional violence unleashed by the Freedom Rides drew the newly installed Kennedy Administration deeper into the Civil Rights Movement. He soon became leader of SNCC, helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, then the largest protest gathering ever held in Washington, D.C., and earned a coveted speaking place as one of the “Big Six” civil rights leaders at the podium set up between the Lincoln Memorial and the Reflecting Pool.

The capital event went off peacefully in spite of concerns by the Kennedy Administration and helped build momentum for the White House’s civil rights bill, which Congress passed the following year.

In 1965, within months of President Lyndon Johnson signing the civil rights measure into law, the world watched horrified as Alabama state troopers mercilessly bludgeoned peaceful protesters attempting to cross the Selma bridge named for a Confederate general and Ku Klux Klan leader. Lewis, his brain swollen by repeated blows to the head, was taken to Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston for care.

Opposition in Congress to the Voting Rights Act withered after the Selma march. President Johnson presented Lewis with the pen he used to sign the bill.

In the wake of Lewis’ death, his closest friend in Congress, U.S. Rep. Jim Clyburn (D-S.C.), has urged Alabama officials to rename the Pettus Bridge in his honor. Clyburn has also proposed naming an updated voting rights law after Lewis, who risked his life traveling through the back roads of the South to enfranchise a generation held down by Jim Crow. The new law aims to reverse the impact of a controversial Supreme Court decision that weakened the original measure.

In Lewis’ world view, cultivated through his study of Gandhi-style civil disobedience with the Rev. James Lawson at the American Baptist Theological Seminary, the sacrifices of protesters willing to endure imprisonment and risk death were part of a moral re-ordering of the universe, the arc that “bends towards justice,” in the words of the Boston abolitionist preacher, the Rev. Theodore Parker.

Suffering, Lewis said, “touches and changes those around us as well. It opens us and those around us to a force beyond ourselves, a force that is right and moral, the force of righteous truth that is at the basis of human conscience.” The bonds of sacrifice and struggle, in Lewis’s view, were essential in creating what he called “the beloved community.”

To Lewis, forgiveness was just as important as struggle in creating that community. In 2009, a former Ku Klux Klan supporter named Elwin Wilson came forward asking contrition for having beaten Lewis during a 1961 Freedom Ride at the Greyhound bus station in Rock Hill, S.C. Lewis accepted Wilson’s apology and took him on a round of TV appearances to show that “love is stronger than hate.”

John Lewis in Boston, 1994.

Like King, Lewis denounced militarism and the excesses of capitalism, earning him surveillance from J. Edgar Hoover’s communist-obsessed FBI. He opposed America’s misadventures in Vietnam and received conscientious objector status.

Often called “the conscience of the Congress,” Lewis’ influence on Capitol Hill came more from the moral force of his witness than legislative legerdemain.

John Robert Lewis was born in 1940 to an impoverished farming family in the Black Belt of rural Alabama. He was a high school student when he heard broadcasts by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., surrounding the Montgomery bus boycott in the state capital.

“Every minister I’d ever heard talked about ‘over yonder,’ where we’d put on white robes and golden slippers and sit with the angels,” he wrote in his memoir in a passage cited by the Washington Post. “But this man was talking about dealing with the problems people were facing in their lives right now, specifically in the South.”

At 18 years old, Lewis wrote a letter to King, who summoned him to Montgomery. The future King disciple boarded a bus to meet with the minister at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church and continued following his call the rest of his life.

As a college student working his way through school, Lewis helped organize lunch-counter sit-ins in Nashville. Following the success of the Freedom Rides, capped off by a favorable Supreme Court decision striking down segregation in public accommodations, he became SNCC director. The position put him in the luminous company of King, who headed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; National Urban League Executive Director Whitney Young; Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters founder A. Philip Randolph; Congress of Racial Equality founder James Farmer; and NAACP Executive Director Roy Wilkins.

In early 1963, “The Big Six,” as they were dubbed by the press, met with Kennedy in the White House and refused his request to cancel the August march, which the president feared would lead to violence and set back the cause of civil rights. The youngest and most militant of the leaders, Lewis planned to take a hard line in his speech to the vast crowd but was persuaded by King and the others to tone down his remarks. Just a few years earlier, he had ignored admonitions by NAACP legal counsel and future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall to practice restraint and avoid protests in Nashville risking jail-time. This time, however, he listened.

Only 23 when the march took place, Lewis stepped up to the podium in the swampy heat of a Washington summer to deliver a watered-down but still stern warning to the audience spread out below the marble pillars of the Lincoln Memorial as well as to the millions listening around the world. “If we do not get meaningful legislation out of this Congress, the time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington,” said Lewis. “We must say, ‘Wake up, America, wake up! For we cannot stop, and we will not be patient.”

Lewis’ activities alarmed his parents and grandparents, who discouraged his civil rights work. But that dangerous calling paved the way for the many gains of the movement. President Barack Obama, before taking the oath of office in 2009, told Lewis, tears streaming down his cheeks, that his election would not have been possible without the movement Lewis carried on his broad shoulders.

After the success of the Voting Rights Act, Lewis clashed with emerging Black Power advocates who eschewed nonviolent protest for a more confrontational stance. Stokely Carmichael, later renamed Kwame Ture, became SNCC chairman in 1966 and pushed out Lewis, whom he called “a little Martin Luther King.”

After a brief period in community redevelopment, Lewis joined the presidential campaign of U.S. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, who, as attorney general, had called in the National Guard to protect Lewis, King and the Rev. Ralph Abernathy when they sought protection from armed white supremacists surrounding the Montgomery church where they had taken refuge during a Freedom Ride.

Lewis was in Indianapolis with Kennedy when King was assassinated and convinced the senator not to cancel a planned rally in an impoverished black neighborhood. Kennedy ignored the mayor’s advice and heeded Lewis’ instead. Kennedy helped keep the city calm with measured and heartfelt remarks delivered from the bed of a pickup truck in a public park. Lewis was in Los Angeles when Sirhan B. Sirhan shot Kennedy in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel.

In an oral history given to the Edward M. Kennedy Institute in Boston, Lewis explained why he became so close to the senator. “Robert Kennedy asked a lot of questions. Not just asked questions, but he talked and said what we’ve got to do, what we must do. He had passion. He felt it in his gut,” said Lewis. “He did everything possible, I think, in a very short time, to try to make real the hopes and dreams, not just of his brother but of the administration.”

In turn, Kennedy admired Lewis’ physical and moral courage. In long conversations with the passionate activist in the years leading up to his fateful presidential campaign, Kennedy acquired a better understanding of the agony of racial bias and its devastating burden on families and communities suffering America’s original sin.

Like so many, Kennedy found deep truth in Lewis’ belief in the eventual triumph of faith, reason and justice.

“You cannot stop the call of history,” Lewis said in response to recent protests over racial injustice sparked by the death of George Floyd. He spoke of tactics used by the militarized police of 2020 but could have been talking about Sheriff Bull Connor and the savage police dogs unleashed on protesters in 1965 Alabama. “You may use troopers, you may use fire hoses and water, but it cannot be stopped. There cannot be any turning back. We have come too far. We’ve made too much progress to stop now and go back.”

After the 1968 campaign, Lewis became executive director of the Southern Regional Council’s Voter Education Project, which registered African American voters across the South. He ran unsuccessfully for a U.S. House seat in 1977 but eventually won a seat on the Atlanta City Council.

In 1986, Lewis prevailed in a bitter Democratic primary contest for Congress against Georgia state Sen. Julian Bond, his colleague from SNCC. Tall and handsome, worldly and sophisticated, Bond cut a sharp contrast to his thick-set, blunt-spoken opponent, who implored voters to elect a “tugboat” rather than a “showboat.” Voters narrowly agreed, sending Lewis to Ronald Reagan’s Washington.

On Capitol Hill, Lewis made his mark as one of the most liberal Democrats in Congress, standing up against Reagan’s accommodating posture towards apartheid; fighting for affordable housing, food stamps, expanded medical care, and fair lending laws; and educating two generations of lawmakers about the Civil Rights Movement.

He was revered by activists for encouraging Americans to cause “good trouble” in the service of justice — a mantra he repeated in commencement addresses and political sermons the rest of his life.

As a politician, Lewis took bold stances on policy and stood by friends. Wearing one of his signature ministerial dark suits, crisp white shirts and rep ties, Lewis came to Boston in 2018 to campaign for U.S. Rep. Michael Capuano during a primary challenge by Boston City Councilor Ayanna Pressley, who defeated Lewis’ colleague to become the first African American woman elected to Congress from Massachusetts.

Lewis was an outspoken opponent of President Donald Trump and his policies undermining voting rights, health care, environmental protections and immigrant rights, but especially his divisive remarks on race.

His last public appearance was at a Black Lives Matter event where activists had painted the movement slogan on a street in Washington, D.C., near the White House.

Lewis is survived by a son, John Miles-Lewis. His wife, Lillian Miles, a former librarian and Peace Corps volunteer, died in 2012.

The Rev. Jeffrey Brown, associate pastor of the Twelfth Baptist Church in Boston, met Lewis when he was a teenager through his mother, who worked for the first black speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly. He recalled the late civil rights leader as someone who inspired his work in the ministry and activism, causing “good trouble, necessary trouble.”

“John Lewis’s work in the Civil Rights Movement and SNCC had already made him a legend in my mind when I met him,” said Brown. “I remember his handshake, his encouraging me, and the steely look of determination in his eyes. He never gave up hope in the future.”