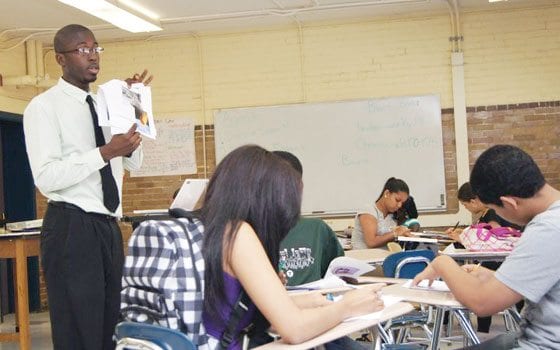

Scattered across a classroom at Newcomers Academy in Dorchester are bright charts and diagrams drawn in every color of the rainbow.

They show the human digestive system and Newton’s laws of motion. The students hunch over the diagrams as they study for the physics portion of their final exam, working in groups on a handout that asks to them describe “motion” and “rest,” as well as naming all of Newton’s laws.

They read the questions aloud as each group discusses the answers in different languages —Spanish and Portuguese rising above the chatter with English woven in between.

“What I can do right now, as far as what I can say to them, that was not happening in September or even January,” Teach for America instructor, Evin Nembhard, 22, said.

At Newcomers Academy, students are grouped not by age, but by English proficiency. Nembhard’s students are between the ages of 14 and 20 who recently immigrated to the United States. Even though his classes are focused on the sciences, he is tasked with teaching basic English terminology as well.

“You have to use a lot of pictures, you have to speak much more slowly, be very careful and deliberate in the words you choose.” He said he front-loads a lot of the vocabulary, such as the terms “rest” and “motion” when discussing “inertia,” or Newton’s first law of motion.

Nembhard is one of 50 Teach for America (TFA) participants completing the first year of the program in metro Boston. Like Nembhard, his 49 peers also overcame tough challenges as they spent the year attempting to close the achievement gap.

At the beginning of the school year, each TFA participant set lofty, yet measurable goals. Using the tools provided for them, they then tried to achieve them. At the end of their first year in Massachusetts, before the test scores are even returned, the sense is that the program is a success.

“Principal satisfaction has been high,” said Josh Biber, executive director of TFA — Greater Boston, “One hundred percent of our principals in February said our folks were as good or better as other beginning teachers. … We are actually seeing that translate into hiring, so last year at this time very few of our folks had secured their positions and today more than half of our teachers already have their positions.”

And the program is growing. Next year, 75 new teachers will work under TFA guidance. They were chosen out of a selective application pool that included 1,500 local applicants and almost one in five Harvard graduates. These teachers will work in the same public school districts as the current 50: Boston, Cambridge, Chelsea and Revere, as well as in charter schools and the newest community to come on board, Lawrence.

Biber credits the growth and success of the program not only to legislators who said they feel a new-found sense of urgency to close the achievement gap coupled with the need to have new teachers in Greater Boston.

Biber also credits the population of more than 700 TFA alumni who live and work in the area, of which 30 are school principals. He explains that one of the reasons the first-year TFA teachers have adapted to Boston is that the alumni group understands the need for mentoring first-year teachers.

“I felt like we all had great people around us who were willing to help us because they knew we were first time teachers,” said Nembhard, “they knew how crazy that time was for us and they were able to provide us with resources.”

Nembhard said that TFA’s training program provided him with most of the tools he needed. He sought help from the more experienced teachers around him on how to put those new skills into practice.

For many of his greatest successes, he credits conversations with his principal and also his assigned veteran-teacher, Tony King. He said with the help of King, a founder of Newcomers Academy who specializes in English as a second language (ESL) education, he was able to be flexible with his curriculum to meet the needs of his students.

When his students discuss their short-term goals, it is not just academic success they are after, but to learn English. It was important then for Nembhard to develop a curriculum that would not discourage them.

He initially taught a full biology curriculum, but during the semester he realized that the subject was too language intensive and he adapted his classes to a general science curriculum, including chemistry and physics which use’s more numbers and figures.

“My big goal for the second semester was to reinforce and impart strong scientific thinking skills,” he said. “More so than knowing what Newton’s laws of motion were, more so than knowing how to use the periodic table but knowing how to approach a problem, identify what you know, identify what you don’t know and then to put things together and to follow a logical conclusion.”

Though there is no Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) for general science curriculum, Nembhard’s students took the biology MCAS this year based on their first semester of education. Next year he hopes to take his students through an entire year of active chemistry or physics so that they can participate in MCAS and he can measure their success. He says, that based on what he has seen this year, the students can succeed even with the language barrier if they take the class for the full year.

The language barrier was more than a challenge for Nembhard this year; it opened his eyes to a harsher reality than he envisioned for low-income students. He took the position because he clicked with the administration and felt up for the challenge. Growing up in a single-parent home in downtown Providence and finding the kind of academic success that earned him a spot at Harvard University — Nembhard thought that he was a “poster child” of the achievement gap and that he understood what it takes to close that gap.

“The achievement gap has facets to it that you never hear about,” said Nembhard, “Rarely are people talking about the immigrants who don’t even know how to use the bus to get to their school or don’t understand the culture in general, let alone the school culture that you are trying to cultivate.”

He said that he hopes people consider all factors in why students may face learning challenges, and he believes in TFA’s message that no challenge is too great to overcome.

Biber describes the achievement gap as a moral and social injustice that can be solved by raising instructor quality and student’s expectations. He believes this can be done by hiring the right people and using measureable, transparent strategies.

“Despite how big and challenging [the achievement gap] is, it is a solvable problem,” he said. “I deeply believe at its root all of our kids are smart, they can all learn at the highest level.”

Biber believes that the TFA formula is one that can take the lowest achievers from low-income areas and turn them into the highest achievers in the state. “Work hard,” he said he explains to students. “Get smart and we are going to get results.”