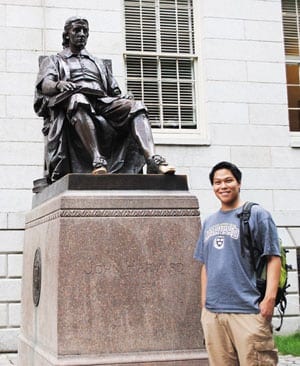

When he arrived in Cambridge, he was astounded to see trees.

There are no trees in his Native Greenland, the Northernmost inhabited part of the planet, that is frozen over for most of the year. He is Anaukak Allen Matthew Henson, a 23-year-old Inuit (Eskimo) and the great grandson of the American co-discoverer of the North Pole in 1909, Matthew Henson.

Anaukak Allen is the first Greenlandic Eskimo student to attend Harvard.He entered Harvard mid-June after completing Gymnasium (high school) in Nuuk, Greenland with hopes of studying English and film animation.

Before he departed Greenland, the television station of Nuuk came to his home to film a special for the Inuit communities scattered throughout Greenland called, “An Eskimo goes to Harvard.”

Last year, Allen (as he prefers to be called) was selected by a Japanese college to travel to Japan for training in film animation to use for educational purposes in his native Greenland. Unfortunately, because of the tragic earthquake and tsunami in Japan, he was recently informed that he could not travel there to fulfill his educational needs.

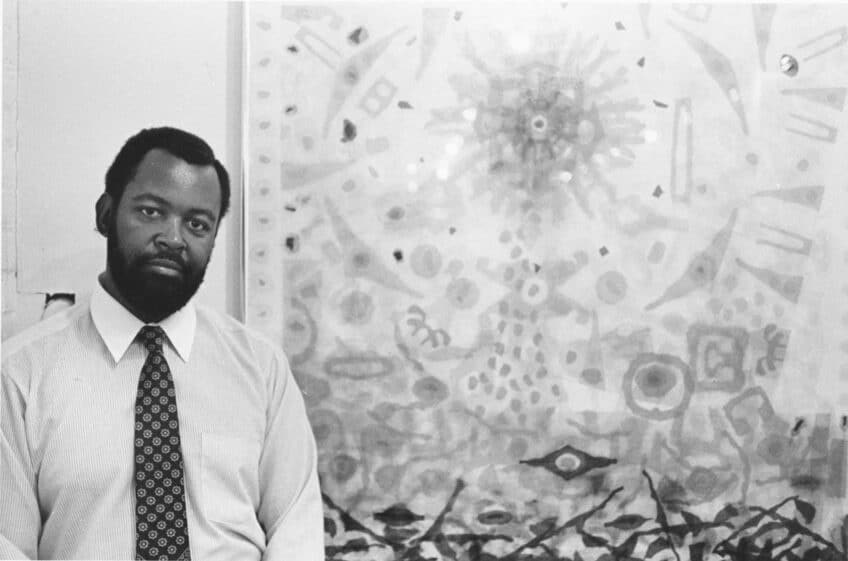

The family then turned to Dr. S. Allen Counter, professor of neurology at Harvard and a longtime friend to the Greenlandic family, to ask if there was any opportunity for Anaukak Allen to attend classes in English and film animation at Harvard.

Dr. Counter in turn contacted professor Donald Pfister, dean of the Harvard Summer School, and professor Michael Shinagel, dean of the School of Continuing Education, to seek support for this ambitious young man, who had become an indirect victim of the tragic earthquake in Japan.

Both Pfister and Shinagel welcomed Anaukak Allen, and Dean Shinagel provided him with a full scholarship to the summer program at the Harvard School of Continuing Education.

Dr. Counter then turned to the American Embassy in Denmark to secure the proper visa for Anaukak to enter the country as a student. He later acquired a gift to cover the expenses of flying from Greenland to the United States from Harvard alumnus, Sean T. Brady ’89, HLS ’92.

Brady was one of the students Dr. Counter selected in 1987 to host the 80-year-old Greenland Inuit sons of Matthew Henson and Robert Peary on their first visit to the United States.

On April 6, 1909, Matthew Henson, an African American from the Washington, D.C. area, stood at the top of the Earth, the North Pole. With him were a U.S. Navy Commander Robert Peary, and four Polar Inuits (then called Eskimos) Ootah, Seegloo, Egingwah, and Oqueah. At that moment, Peary claimed the North Pole for the United States of America since he and the others in his group, were the first men to reach the North Pole.

In his book, “North Pole Legacy,” Dr. Counter wrote that when Henson and Peary returned to America, only Peary was recognized as the discoverer of the North Pole. Because of the racial attitudes in the United States in the early 1900s, Henson and the Inuit men were left out of the picture and the history books.

It was not until roughly 50 years later that Matthew Henson was welcomed to the White House by President Dwight Eisenhower in recognition of his contributions to the North Pole discovery. However, upon his death in 1955, Henson was buried in a common grave in New York’s Woodlawn Cemetery, while Peary was buried with a magnificent monument in Arlington National Cemetery.

In 1986, Dr. Counter was exploring Northwest Greenland where he discovered that both Peary and Henson had fathered children with Inuit mothers in 1906. The two sons, Anaukak Henson (Anaukaq Allen’s grandfather) and Kali Peary, were alive and well at 80 years of age in the Northern most habited village on Earth, Qaanaaq, Northwest Greenland.

Both men asked Dr. Counter to help them travel to the land of their fathers to meet their relatives, and to lay wreaths at their gravesites. In 1987, with the help of President Ronald Reagan, Dr. Counter was able to travel with the sons of Henson and Peary on a U.S. Air Force plane from Greenland to the United States, to meet their American relatives for the first time and to lay wreaths at their father’s gravesites.

In the following year, Dr. Counter requested and received from the President of the United States a special order to disinter Matthew Henson from a common grave in New York City, and to reinter his remains beside those of Robert Peary with a fitting new monument in Arlington Nation Cemetery.

In 2009, Dr. Counter fulfilled a promise to the 80-year-old sons of Henson and Peary that he would have their fathers remembered at the North Pole on the centennial of their historic discovery in 1909.

Dr. Counter traveled to the top of Northwest Greenland in April 2009 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the North Pole discovery with the descendents of both Henson and Peary, including now Harvard student, Anaukak Allen Matthew Henson.

In keeping his promise to the sons of Henson and Peary, Dr. Counter transported a Harvard Centennial Commemorative Case/Capsule containing documents from both Matthew Henson and Robert Peary to the precise North Pole on board the U.S.S. Annapolis submarine on the morning of April 6, 2009.