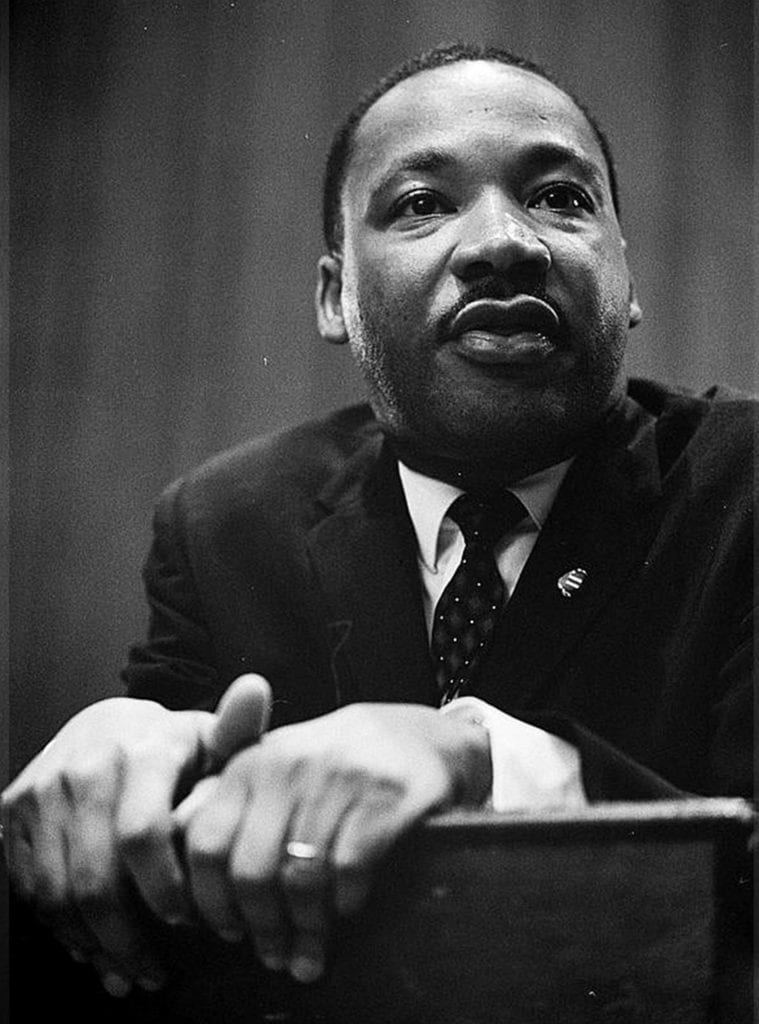

Martin Luther King Jr. first came to Boston in 1951 to study at Boston University’s School of Theology. He received a Ph.D. in Philosophy in 1955.

King lived at 397 Massachusetts Avenue with a former classmate from Atlanta’s Morehouse College. Their apartment became the meeting place for the Philosophical Club, a group of black students they organized to discuss the issues of the day.

The same year King arrived in Boston, his future wife Coretta Scott came here to study at the New England Conservatory of Music. In early 1952, the two met. A romance blossomed and in June 1953, they were married in Heilberger, Ala.

After their wedding, the Kings returned to their studies in Boston and made their new home in a four-room apartment near the Conservatory.

At Boston University, King studied philosophy and theology under Edgar S. Brightman and L. Harold DeWolf, two leading advocates of personal idealism. Through this philosophy, King strengthened his idea of a personal God and formed his belief in the dignity and worth of all human personality.

During his student years at Boston University, the historic Twelfth Baptist Church (now on Warren Street in Roxbury) was an important part of King’s life. He worshipped, taught religious classes and preached Sunday morning sermons at the church.

By the winter of 1954, King began thinking about beginning his ministry. He was offered and took a job at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala.

In June 1954, Coretta Scott King finished her studies at the Conservatory. The couple closed up their Boston apartment and went south.

The Boston years had sharpened King’s gift as a religious thinker and leader. When he was needed, King returned to the city.

Among the most important things King did for Boston were to lead a massive demonstration in April 1965, and to solidify the fight against racism in the Boston Public Schools.

The years 1964-65 saw debate over de facto segregation in the Boston Public Schools. Black parents called for the closing of the inadequate Boardman School in 1964. That same year, parents and their supporters boycotted the schools in a protest over unequal allocation or resources in the system and set up the Freedom Schools. King came to Boston to give his support.

He returned in 1965 for a second boycott as the struggle with the Boston School Committee over inadequate and segregated schools. King tried to visit the Boardman School but was turned away by school officials.

When King left Boston in 1954 after finishing his theological studies at Boston University, he was a young minister known by a small circle of friends and admirers. But when he returned to Boston in 1965 to support blacks in their struggle to desegregate the schools, he was an internationally known personality, having won the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize for his nonviolent black struggle for civil rights.

The hallmark of the visit was King’s April 22 speech delivered to a joint convention of the two houses of the general Court of Massachusetts at the State House. This was his first speech before any state legislature in the country.

Boston Globe reporter Wilfred Rogers described the scene in the House chamber: “Spectators stood in the packed galley. Some legislators used camp stools on the crowded House floor. Many edged forward in their seats when Rev. Dr. King warned that segregation isn’t limited to any one section of the nation. He never mentioned Boston or Massachusetts specifically, but he did stress ‘school imbalance’ and ‘de facto segregation.’”

In strong tones, King spoke of the “tragedy” and evils of school segregation. Again, while not mentioning Boston by name, it was clear that his remarks were targeted at the state and Boston.

“Now is the time to end segregation in the public schools,” King told the State House gathering. “Young boys and girls must grow up with world perspectives. Segregation debilitates the segregator as well as the segregated.”

The day before the speech, King had visited the Patrick T. Campbell Junior High School in Dorchester. The school, later renamed for King, had a virtually all-black student body and faculty.

Rogers’ Globe report said that motorcycle police cars protected King’s entourage along Blue Hill and Lawrence Avenues as a precaution against death threat calls received by the Boston Police Department and the NAACP.

With bullhorn in hand and speaking from the elevated entranceway to the school, King told the cheering crowd:

“Today I am happy to become a member of PUSH — Parents United to End School Hoax, a local desegregation group.”

King attempted to arrange a visit with former Boston School Committee President Louise Day Hicks. The meeting collapsed when Hicks refused to include local civil rights and school activists in the talks with the Nobel laureate. The struggle over school desegregation and education was the primary focus for King while he was in Boston.

On April 22, he led a major protest march from the Carter Playground in the South End to Boston Common in support of school desegregation before addressing the Massachusetts Legislature that afternoon.

The Massachusetts Racial Imbalance Act was passed in 1965, and King’s voice and actions were part of that legislative movement toward school desegregation.

In the opening of his address to the Legislature, King said, “Let me hasten to say that I come to Massachusetts not to condemn but to encourage. It was from these shores that the vision of a new nation conceived in liberty was born, and it must be from these shores that liberty must be preserved; and the hearts and lives of every citizen preserved through the maintenance of opportunity and through the constant creation of those conditions that will make justice and brotherhood a reality for all of God’s children.

“Although we have come a long, long way in the struggle for brotherhood and the struggle to make civil rights a reality for all people…we still have a long way to go…we do not have to look very far to see that…we only need to open out newspapers, or turn on our televisions or look around in our own communities, and we realize that there are still problems alive that reveal to us that we have not reached the promised land….”