“Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts.”

ITHACA, N.Y. — History’s famous word collaborators include Gilbert and Sullivan, Lennon and McCartney, Woodward and Bernstein.

While those pairs were contemporaries, William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White worked four decades apart. Yet the little-known turn-of-the-century Cornell University English professor and his universally famous student produced a classic that has become one America’s most influential and best-known guides on grammar and usage.

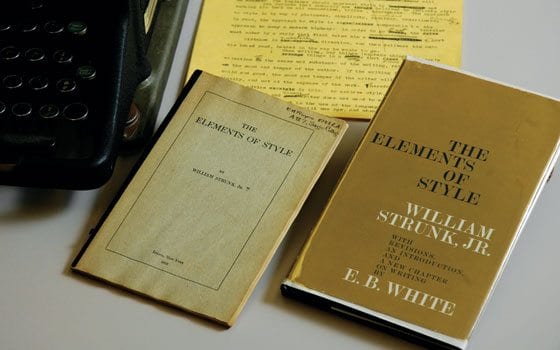

Strunk and White’s “The Elements of Style” has sold more than 10 million copies since its initial publication in April 1959. Its present-day publisher, Longman Publishers, has put out a special black leather-bound, gold-embossed edition in tribute of the 50th anniversary.

“It’s ubiquitous,” said Elaine Engst, director of Cornell’s division of rare and manuscript collections. “There have always been writing guides. But this is the one that left its mark.

“Part of that was White’s fame, but the book also was inexpensive and accessible and has stayed true to Strunk’s original focus on brevity and clarity,” Engst said.

Strunk and White’s success is the result of an “emphasis on plain style being preferable to more ornate kinds of writing. Simple rather than complex. Native rather than foreign. Active rather than passive. Verbal rather than nominal,” said Dennis Baron, a professor of English and linguistics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Baron is the author of “Declining Grammar and Other Essays on the English Vocabulary” and “Guide to Home Language Repair.”

Strunk, a native of Cincinnati, began teaching English at Cornell in 1899 after getting his doctorate there in 1896.

“He is remembered as being very concise, which meant his lectures tended to be very short. To fill time, he usually said everything three times,” Engst said. Despite his rigorous attitude about writing, students described Strunk as friendly and funny.

In 1918, he self-published a writing guide for his students, which they could buy at the campus bookstore. Its main precept was “omit needless words.”

“The little book” was 43 pages. It detailed eight elementary rules of usage, 10 elementary principles of composition and “a few matters of form,” as well as containing a list of commonly misused words and expressions.

In 1920, Harcourt Brace took over publication. In 1936, Strunk joined with Cornell colleague Edward Tenney to produce “The Elements of Practice and Composition,” a more elaborate version of Strunk’s original writing guide that included exercises as well as rules.

While it would have been widely available, there’s no evidence that Strunk’s manual found any audience beyond the Cornell campus, Engst said. Even there, it fell into disuse after Strunk retired in 1937. He died in 1946.

Elwyn Brooks White took English with Strunk in 1919.

He had long since lost his book — though he remained faithful to many of Strunk’s writing rules — as he rose to become one of America’s greatest essayists with The New Yorker magazine and immortalized himself as a children’s author with “Charlotte’s Web” and “Stuart Little.”

Strunk’s “Elements of Style” probably would have vanished for good if someone had not stolen one of the two copies in the Cornell library in 1957 and sent it to White.

In his “Letter from the East” column dated July 15, 1957, White trumpeted “the little book,” recalling its “rich deposits of gold” and eloquently ruminating on the valuable lessons he learned, lauding Strunk and his devotion to lucid English prose.

Jack Case, an editor at Macmillan, was enticed by the column and eventually persuaded White to revise, expand and modernize Strunk’s book.

Cornell’s archival holdings include White’s letters back and forth with Case about the project, as well as his original note-filled 1959 manuscript. Cornell also possesses three copies of Strunk’s original 1918 edition and White’s Underwood typewriter.

“We think that amidst the crazy currents now running every which way in freshman English, your essay could draw up a tide that would get this off the beach,” Case implored in one letter.

The 1959 edition was 71 pages and cost $2.50 in hardback; a paperback sold for $1.

“This, together with, on the other side of the Atlantic, H.W. Fowler’s ‘Dictionary of Modern English Usage,’ are the two style books that are generally held up as the authorities,” said Baron, a member of the National Council of Teachers of English.

White later revised the book in 1972 and 1979, expanding it to 85 pages, as it also became a standard reference work for journalists, ad agencies and writers beyond the classroom. White died in 1985. A fourth edition appeared in 2000 with a foreword by White’s stepson, Roger Angell.

The 50th anniversary edition has 95 pages but also includes several pages of testimonials from famous literary figures past and present, Angell’s foreword, an introduction written by White to the 1979 edition and an afterword by Charles Osgood, anchor of “CBS News Sunday Morning” since 1994.

After 30 years of teaching English, Sharon Gross said she has found the book’s influence waning some in the classroom, but said that “for the purist, it continues to be an invaluable source for those who demand conciseness and brevity in writing.”

Strunk and White, though, is possibly needed even more today because text and instant messaging on computers and cell phones have helped erode writing skills, said Gross, who teaches at Chamberlain High School in Tampa, Fla., and is a member of the advisory council for the National English Honor Society for High Schools.

“The main appeal of the book is the idea of, ‘Say what you mean and mean what you say,’” said Gross.

Strunk’s focus on usage and composition in a few concise rules helps the novice writer quickly find a comfort zone with his own writing; the clarity and delivery of Strunk’s own rules lends credence to the writing philosophy of “show, don’t tell,’” Gross said.

“A ‘good’ writer still values the elements Strunk introduced in 1918,” she added.

(Associated Press)