One group of activists is seeking the removal of Peter Faneuil’s name from the building he constructed for the city using funds derived from the slave trade. Mayor Martin Walsh backed a plan for a memorial in the form of a slave auction block next to Faneuil Hall, but that plan was derailed after the artist who designed the concept withdrew from the project, prompted by opposition from the NAACP Boston Branch.

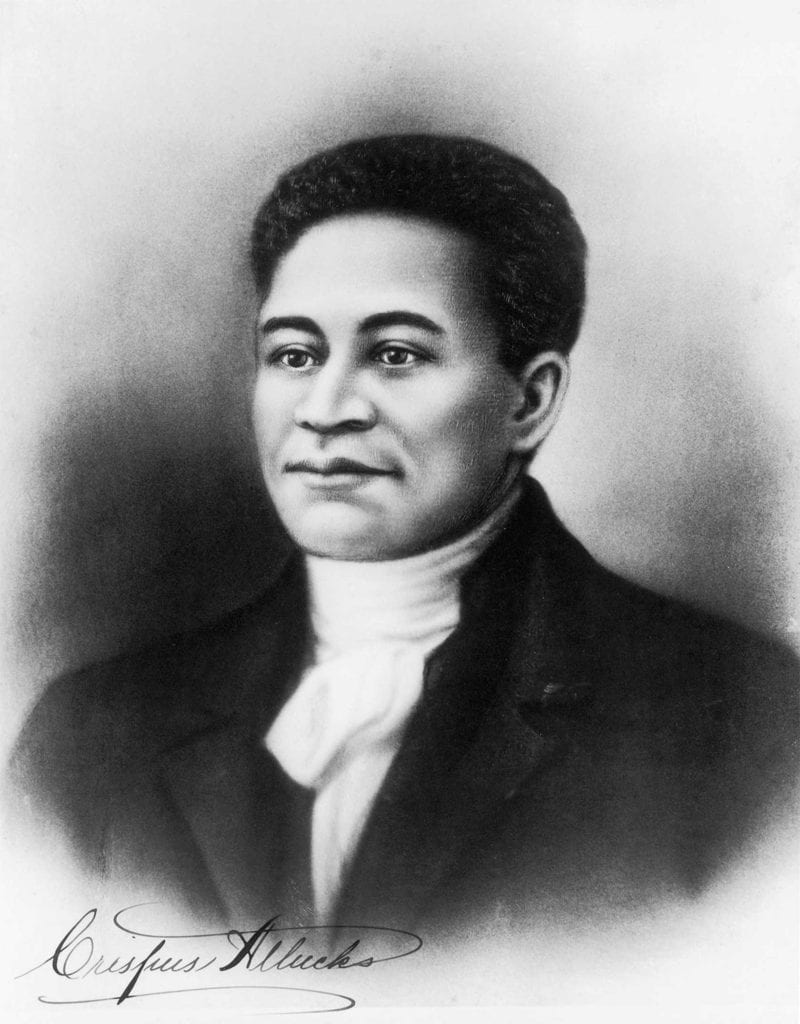

Elsewhere in the seemingly tortured landscape of black history in downtown Boston, a small group of black community activists is pushing another idea: a statue of Crispus Attucks.

Attucks, who was the first to fall in the Boston Massacre — the 1770 prelude to open armed conflict between British troops and the colonists — has been memorialized in a plaque with the names of massacre victims placed on the Boston Common. But as one of the earliest martyrs in the fight for independence and one of the most lionized black Bostonians of the Colonial era, Attucks hasn’t received his due, says Haroon Rashid, who is spearheading a project to honor Attucks.

“The ultimate goal is to have a statue of Crispus Attucks in a public space in Boston,” said Rashid, a Boston native and president of the Friends of Crispus Attucks Association: Boston.

Rashid says his group is advocating for a life-size statue of the fallen patriot to be installed behind the Old State House, at the scene of the massacre.

The organization has not yet raised funds for the statue project.

Attucks, a Colonial martyr

Attucks is a historical figure steeped in mystery. Said to be the child of an African father and Native American mother, Attucks was born into slavery in Framingham. The first reference to Attucks in the historical record comes 20 years before the massacre in the form of an advertisement for an escaped slave in a 1750 edition of the Boston Gazette.

“RAN-away from his Master William Brown of Framingham, on the 30th of Sept. last, a Molatto Fellow, about 27 Years of Age, named Crispas, 6 Feet two Inches high, short curl’d Hair, his Knees nearer together than common; had on a light colour’d Bearskin Coat, plain brown Fustian Jacket, or brown all-Wool one, new Buckskin Breeches, blue Yarn Stockings, and a check’d woollen Shirt.”

It’s unclear whether Attucks was ever re-captured. In the decades after the massacre, descendants of the family that enslaved Attucks said that the family had freed Attucks prior to the massacre.

But Attucks may have become a seaman or simply disappeared into the crowd in Boston. Former state Rep. Byron Rushing says there was a sizeable community of free blacks living and working in Boston in the 1750s, still three decades before slavery was abolished in post-revolutionary Massachusetts.

“You could walk down the street in Boston and see black people,” he said.

The second and last official mention of Attucks in the historical record is his autopsy following the massacre. He and four others became instant martyrs in the cause of the independence-minded colonists. Until the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the massacre was memorialized yearly by the revolutionaries.

After July 4 took precedence as the holiday marking independence, memory of the massacre began to fade.

It took the abolitionist movement to revive the memory of Attucks and the four white colonists who died by his side.

In the 1850s, Boston abolitionist William Cooper Nell sought to persuade the Legislature to erect a monument to Attucks, in whose heroic death he saw a potent symbol of blacks’ sacrifices for the United States. After the Legislature balked, Nell in 1855 published “The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution,” culling source material from government archives and interviews with veterans of the war of independence and their descendants.

After the 1857 Dred Scott decision ruled that blacks had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” effectively denying them citizenship, Nell began yearly commemorations of Attucks’ death in Boston.

“The story of Crispus Attucks is really of how he was used as a symbol for the black presence in the colonies,” Rushing says.

In Boston today, there’s little beyond the plaque on the Common that pays homage to Attucks. In the St. Joseph’s housing cooperative on Washington Street between Cedar and Circuit streets in Roxbury, there’s a small street called Crispus Attucks Place. And on Humboldt Avenue, there’s a Crispus Attucks Children’s Center.

Rashid says the ideal location for the statue would be at the site of the Massacre, behind the Old State House, a site currently marked with a circle of stones and a plaque explaining the significance of the event. The Friends of Crispus Attucks Association: Boston has teamed up with the Bostonian Society and City Councilor Andrea Campbell to push for the memorial.

“We look at this as a unique opportunity to inform the public about the role Attucks played in this country becoming a republic,” says group member Bob Redd.

Community consensus needed

Rushing, while he supports a memorial to Attucks, cautions that community members should be consulted as different groups advance ideas for honoring blacks in Boston. He advises forming a list of prominent Boston black women and men and prioritizing who should be honored.

“We should ask the whole black community,” he said.