You are what you eat, the saying goes, but for culinary historian Jessica B. Harris, you are also what your ancestors ate.

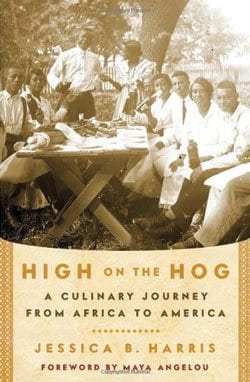

In her new book, “High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America,” Harris traces the history of African American eating, from the open-air markets of 16th century Western Africa to the Food Network’s hit show, “Down Home with the Neelys.”

As Harris shows, African American cuisine began in Africa. While millions of Africans were forcibly taken to the New World in the transatlantic slave trade, remnants of home went with them — okra, watermelon and black-eyed peas. Soon, the plants were grown all over the American South, but even after their Americanization, they remain “indelibly connected to African Americans.”

The “eternal confusion about yams and sweet potatoes” can also be traced to these Africans in America, Harris says. Yams are native to the African continent, while sweet potatoes — a distinct root vegetable — are indigenous to America. However, Africans continued to use their own vocabulary for the tubers they saw in America, and eventually “yam” became another word for sweet potato in the South.

But food had other uses at the time, Harris writes. Slave ships crossing the Middle Passage were frequently staffed with an African cook. This position was of critical importance to the ship’s profits, as the food slaves ate determined whether they would survive the treacherous journey. And the enslaved understood this. Many aboard went on hunger strike, what Harris calls “a first culinary step in resistance to enslavement.”

By this time, “The Big House kitchens were slowly having Africa’s way with the tastebuds of the South,” according to Harris. Cayenne pepper, gumbo, okra soup and rice-based dishes like Hoppin’ John all made their way onto American plates, as Southern cuisine began to take on African dishes as their own.

In an interview with the Banner, Harris, the daughter of a dietitian, explained that she grew up eating well. She attended the United Nations International School in New York City, and there, was exposed to foods from around the globe. In college, she spent a year abroad in France, a country she credits for her “culinary epiphany.”

Later, Harris worked as the travel editor for Essence magazine, and continued to connect with food across the world. Now a professor of English at Queens College in New York City, Harris is the author of several cookbooks and culinary histories.

In the free North, food also became a route to financial stability for African Americans. Blacks used food — particularly through catering — to start their own businesses, becoming “black culinary entrepreneurs.”

Through World War II, “African Americans’ culinary abilities,” Harris writes, “continued to provide a springboard to financial success and community growth.” Long before Oprah Winfrey, in 1947 Lena Richard became the first African American woman with her own television show — a cooking show. And Freda DeKnight was named food editor of Ebony magazine in 1946, and quickly rose to national prominence through her writing, public speaking and cooking demonstrations.

By the mid-20th century, food service was used to assert another kind of independence. In 1960, four black men sat down at a restaurant in Greensboro, N.C., and asked to be served — a simple act that kicked off the civil rights movement. Later, restaurants became common meeting places for Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders in the movement.

Food itself also became an important battleground during the civil rights movement. Earlier, African American cuisine was frequently referred to as “plantation” food, but by the 1960s, it became soul food. Quickly popularized, soul food “went hand in hand with a growing pride in race and in self in the African American community.”

While African Americans increasingly connected with the food of their ancestors, by the end of the 20th century their palate was also expanding to encompass the growing diversity in their present communities. The vegetarianism espoused by Dick Gregory, the dietary restrictions of the Nation of Islam, and food from the Caribbean was soon just a part of the African American diet as fried chicken, pork chops and turnip greens.

But along with this diversity, another trend was also growing in the African American community — “culinary apartheid.”

“African Americans and indeed all who shop in ghettoized areas out of the mainstream were being offered second-rate comestibles sold at first-class prices and fast-food joints,” Harris writes of Brooklyn, N.Y. in the 1980s. “We were getting stuck with over-processed foods, low-quality means and second- or third-rate produce.”

“The poor and the working classes,” Harris continued, “were growing fat and unhealthy on genetically engineered foods, process foods, and fast-food meals.”

Food inequality also manifests in another area, Harris argues. While America has recently witnessed an explosion of celebrity chefs, “African Americans who had toiled in homes and restaurants since the origins of the country were once again on the fringes of the new bonanza.”

“It seemed that the days when blacks gained fame and fortune through food had ended just at the point when the culinary realm became a profession of honor and not a service job.”

“There are few if any African American superstar chefs,” she said in the interview, and then offered a challenge to name one.

Although no black celebrity chefs came to mind, one black woman is changing the country’s food landscape — Michelle Obama. The Obamas are not addressed at length in her work, but Harris lauded the first family for opening “an extraordinary new chapter” in African American culinary history.

From all this history, one culinary tradition sticks out to Harris, one she hopes all Americans can hold on to — eating together as a family. This practice, she explained, is “extremely important” since it brings multiple generations together, ensures cultural continuity and allows the old to educate the young.

“Nothing is more crucial than that right now.”