Domestic and political plots intertwine in Christopher Shinn’s 2008 play, “Now or Later.” With a strong cast and sleek staging, the Huntington Theatre Company is presenting the American premiere of Shinn’s ambitious but flawed play. The production is at the Calderwood Pavilion of the Boston Center for the Arts through Nov. 10.

At the start of the play, cell phones buzz and a TV screen flickers in the hotel suite where John Jr., the son of a presidential candidate, awaits the election results with his college friend, Matt. John is also nervously awaiting a stream of his father’s supporters, who are pressing him to issue a public apology for an irresponsible act that he dismisses as an “Ivy League kerfuffle.”

The act occurred the night before when John attended a college party wearing a cartoonish costume intended to portray the Prophet Muhammad. A video of his lewd horseplay with Matt, attired as a right wing churchman, has gone viral on the Web and its consequences are escalating by the hour. At first a political liability for John’s father, the video is now inciting potentially violent protests in the Middle East.

Deftly directed by Michael Wilson with scenic design by Jeff Cowie and costumes by David C. Woolard, the production mines the play’s satirical edge.

As the play opens, John Jr. (Grant MacDermott) is giving a long-winded defense of his refusal to apologize, which he regards as a matter of principle. Shrugging off his party behavior as a drunken college romp, he insists on his right to exercise free speech. An apology, he argues, would be yielding that right to the forces of Islamic fundamentalism.

Sharp one-liners soon relieve this verbal overload.

Speaking of his driven parents, John tells Matt, “Everything they do is strategic. Giving birth to me was strategic.”

One by one, a variety of people enter the suite with the same purpose: To persuade John Jr. to issue an apology. First comes Marc (Ryan King), a smug campaign staffer who barely hides his disdain for the candidate’s son.

Following Marc is John’s mother, Jessica. Alexandra Neil injects comic verve into her role as both a political climber and a mother concerned about her son’s recent heartbreak. John has just broken up with his boyfriend, who no longer wanted a monogamous relationship. She asks if Matt might be a new love interest.

When John says no, she prods, “He seemed a little gay.”

John replies, “He’s a socialist.”

Then longtime campaign aide Tracy (Adrian Lenox) arrives. Unlike her colleague Marc, Tracy is fond of John, and she appeals for an apology with steel and affection.

The most nuanced performance is by Michael Goldsmith as Matt, a scruffy socialist and sincere friend who tries to persuade John to apologize based on principle rather than pragmatism.

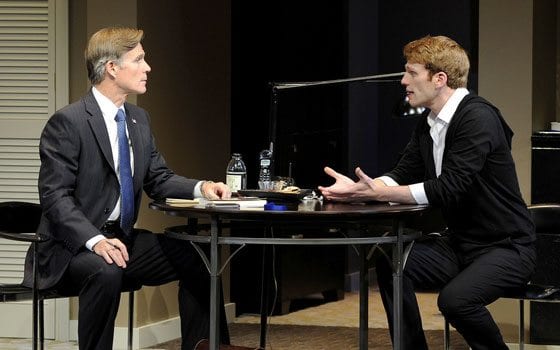

Inevitably, father and son face off. With his chiseled features, Tom Nelis is convincing as John Sr., a father whose conversation with his son on a fishing trip included an analysis of “liberal interest groups.” Yet when confronting John Jr., he is plainspoken: “If you don’t demonstrate contrition,” he says, “innocent lives will be lost.”

Despite MacDermott’s sympathetic portrayal, John Jr. remains something of a politically correct prig. He refuses to use the hotel mini-bar, saying that voters shouldn’t pay for his $15 beer. Never mind that his “Ivy League kerfuffle” is setting off riots overseas.

Performed in 80 minutes without intermission, this enjoyable, fast-moving production cannot overcome a flaw in Shinn’s play: its central character is difficult to care about.