After the dismantling of segregation nearly a half-century ago, African Americans have made tremendous strides: winning the right to vote, upward economic mobility and even the presidency. But alongside these achievements, something else happened — the prison population exploded.

In just 30 years, between 1980 and 2000, the number of U.S. prisoners skyrocketed from 300,000 to more than 2 million, most of them poor people of color. The United States now has the highest incarceration rate in the world, and imprisons a higher percentage of black people than South Africa did under apartheid.

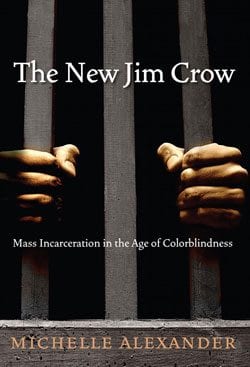

This phenomenon, says law professor Michelle Alexander, has become the country’s newest racial caste system. In her award-winning book, “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness,” Alexander explains how America’s criminal justice system is no longer a “system of crime prevention,” but one of “social and racial control,” similar to segregation in the South.

In an interview with the Banner, Alexander, who will be speaking in Cambridge next Wednesday at 6 p.m., discusses mass incarceration, the fallacy of colorblindness, Trayvon Martin, the “George Zimmerman-mindset” and more.

What do you mean when you say mass incarceration is the new Jim Crow?

It’s important for people to understand that the system of mass incarceration isn’t primarily a system of crime prevention and control. It has become in recent decades a system of social and racial control. I refer to it as the new Jim Crow because even in this age of Obama, even in this era of so-called colorblindness, we’ve managed to recreate something akin to a caste system.

Thanks largely to the war on drugs and the get-tough movement, millions of people — overwhelmingly poor people of color — have been swept into our criminal justice system mainly for nonviolent and drug offenses, branded criminals and felons.Then [they are] ushered into a parallel social universe in which they are stripped of many of the civil and human rights supposedly won in the Civil Rights Movement: the right to vote, the right to serve on juries, the right to be free from legal discrimination in employment, housing, access to education and public benefits.

Many of the old forms of discrimination that we supposedly left behind in the Jim Crow era are suddenly legal again once you’ve been branded a felon. That’s why I saw we haven’t ended racial caste in America — we’ve just redesigned it.

How did this happen?

One of the greatest myths about mass incarceration is that it’s been driven by crime and crime rates, when in fact our prison population has exploded — quintupled — in a period of a few short decades. We went from a prison population of about 300,000 in the 1970s and into the early 1980s, to now well over 2 million.

We now have the highest rates of incarceration in the world, a penal system unprecedented in world history, and this occurred in an astonishingly short period of time — a few short decades. During those decades, crime rates fluctuated. Today, crime rates are at historic lows, but incarceration rates, especially black incarceration rates, have consistently soared.

How has this racial caste system adapted to the colorblind or post-racial age, we supposedly live in today?

This system is colorblind on the surface. Our drug laws on the surface say nothing about race. Unlike the images of the old Jim Crow — the images of overt, latent bigotry and racism — this system has a colorblind veneer that is very seductive.

But the reality is that these colorblind laws, particularly our drug laws, are enforced in a grossly discriminatory manner. Even though studies have shown consistently now, for decades, that contrary to popular belief, people of color are no more likely to use or sell illegal drugs than whites, people of color have been arrested and incarcerated at grossly disproportionate rates. In some states, 80 to 90 percent of all drug offenders sent to prison have been one race — African American.

The drug war has defined as its enemy, folks primarily who live in impoverished, racially segregated, ghettoized communities. It is the people who live in those communities, and their children, who are targeted by the police for routine stops and frisks … [They] are subjected to tactics that would be met with outrage in middle-class white neighborhoods, or on college campuses, even though drugs are equally likely, or more likely, to be found there.

Does your argument apply to the way the United States has conducted the war on terror?

Unfortunately, many of the failed tactics that have been used in the war on drugs have been adapted in the war on terror. One of the important things for people to keep in mind is that you can’t declare a war on a thing, like drugs or terrorism. You declare war on people. In the drug war, the people who became the enemy were poor folks of color, living in ghettoized communities.

In the war on terrorism, a group of people we imagine to be the terrorists have been the targets of investigation and subjected to practices that many believe violate many of our basic constitutional principles and standards.

How does the Trayvon Martin case fit into this?

Even during the Jim Crow era, crimes committed against black people, whether by whites or by other black people, were deemed trivial. It was often very difficult to get any action to be taken on behalf of the victim in those kinds of cases, and that remains true to a large extent today. When this unarmed teenager was killed, law enforcement accepted, relatively uncritically, George Zimmerman’s explanation. They ran drug tests and a criminal background check on the victim, but did no such thing for the man who pulled the trigger.

What I’m concerned about, as all of the politics and the drama surrounding Trayvon Martin’s case plays out, is that we have demonized Zimmerman, rather than acknowledge that Zimmerman’s mindset, far from being unusual or aberrational, is absolutely normal and institutionalized within law enforcement itself.

If Zimmerman had had a badge with his gun, we wouldn’t even know Trayvon Martin’s name today. What Zimmerman did — view a young black teenager as a problem to be dealt with, confronted and controlled for no reason other than his race — is how police treat young black men every day in this country.

If Zimmerman had a badge with his gun, stopping, confronting and interrogating Trayvon about who he is and what he’s doing in that neighborhood, would have been perceived as perfectly normal. And if Trayvon had wound up dead in that encounter, people would have uncritically accepted the officer’s account of the event.

Although people are celebrating the second-degree murder charges that have been filed against Zimmerman, people fail to grasp that it’s not Zimmerman the man who’s the problem — it’s the Zimmerman mindset that infects our society as a whole, that we’ve given license to the police to institutionalize.

There was a tremendous outpouring of anger over the execution of Troy Davis last year. Do you think Americans are starting to understand what you’ve been talking about?

I do think people are waking up to the reality of how our criminal justice system functions. But I’m concerned that these moments of outrage will not prove transformational unless we begin to see these cases as expressions of something that is fundamentally wrong with our criminal justice system.

If we fail to connect the dots and probe more deeply, I think we’ll continue to see that these moments of outrage will subside and reemerge in cyclical fashion. So it’s my hope that through this tragedy, we begin to ask the bigger questions and begin to see that these cases aren’t aberrational, but are reflections of something much deeper that has gone wrong in our criminal justice system and our society itself.

Michelle Alexander will be speaking at Harvard Law School, 1585 Massachusetts Ave., on April 25 at 6 p.m.