Museum of Fine Arts examines the human form in photo exhibit

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, has inaugurated its first gallery space dedicated to photography with the exhibition, “Photographic Figures,” on view through May 10. Displaying about 80 works that portray the human figure, the exhibition is a choice sampling from one of the nation’s largest and most important collections of photography.

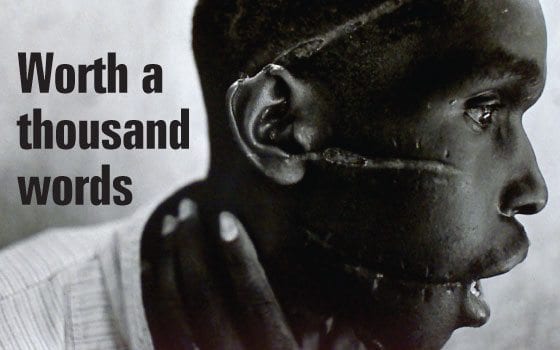

From a searing profile of a Rwandan’s mutilated face by photojournalist James Nachtwey to an iconic — if sterile — image of Irish pop singer Sinéad O’Connor by fashion photographer Herb Ritts, the images on display convey a highly inventive array of creative choices, just about all within the black-and-white palette that dominated photography in the 20th century.

The earliest image on view is “Youth in the Woods (Pan)” (circa 1905-1908) by Clarence H. White, a fanciful scene of a nude boy portraying Pan, the god of nature. The most recent is “Untitled No. 21” (2006) by Jen Davis, a clear-eyed self-portrait of the artist as a large and vulnerable young woman.

Lotte Jacobi’s “Head of a Dancer” (1929) portrays its subject with a Modernist’s eye for the curving geometry of her eyebrows, lips, eyes and the black sphere of her hat. Next to it, an early Yousuf Karsh portrait, “Agnes Macphail” (1934), presents the sculpted profile of Macphail, the first female member of the Canadian Parliament, against the elegant pattern of a black lace veil.

In a self-portrait by German photographer Peter Keetman, “1,001 Faces” (1957), water droplets on a screen reflect tiny images of his face. Using stroboscopic flash technology to create her self-portrait, “Untitled” (1991), Susan Derges stops the motion of a drop of water three times, inserting an image of her eye into the roundest droplet and rendering a faint image of her whole face in the background.

Another inventive self-portrait that employs the tools of science is “Retinas” (1998) by Gary Schneider, who uses a retinal camera to photograph his optic nerves. The resulting images resemble a full moon seen behind branches.

Making the impossible visible is one of the seductive charms of photography, an art that can transform the ordinary into the hallucinatory without entirely leaving reality behind.

After visiting the Belgian Surrealist René Magritte at his home, photographer Duane Michals created a deft homage to the painter, known for deadpan, meticulously accurate renderings of such dreamlike images as a human eye peering from a slice of ham or a locomotive steaming out of a fireplace. In Michals’ photograph, “René Magritte” (1965), the ever-dapper painter is attired in his usual bowler hat and suit, smiling affably as he appears as a shadow on his chair and reflected in a mirror.

“Several Profiles” (1978) offers another droll take on everyday strangeness. The three-dimensional construction by Robert Cumming playfully contemplates masks and public versus private selves. At its center is a photograph of a man and woman facing each other across a table. Framing the image are duplicate profiles of both people, including cutout stencils resembling the portrait silhouettes of vintage valentines; here, however, they are stripped of sentiment.

Michael Spano’s “Classic Back” (1984) echoes the sensuous, elongated nudes of 19th-century French neoclassical painter Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, who rendered the cello-like curves of a woman’s back with an attention to form that predates Modernism. Spano’s composition brings old-world refinement to a mundane setting. Caressing its subject in warm light, the image shows the elegant back of a woman who sits on a peeling metal chair by a radiator.

A number of photographs in the exhibit present the body in motion. A 1944 photograph by Barbara Morgan shows dancer Valerie Bettis performing her renowned work, “Desperate Heart,” as her foot parts parallel waves of fabric. Only the tattooed ankles and muddy feet of two Moroccan women in full-body chadors are visible in “Converging Territories #29” (2004), by Lalla Assia Essaydi, who covers their clothing with essays in Arabic script.

The un-staged and un-manipulated images of documentary photography can likewise have great power. In “Moscow” (1990), journalist Tofik Shakhverdiev shows a trio of Russian soldiers from shoulder down, the stern geometry of their matching satchels, boots and billy clubs conveying an image of brute force.

Straightforward images can also be lyrical in effect, such as a photograph showing the rippling reflections of Budapest pedestrians in a puddle, “Untitled” (about 1930), by Imre Kinszki, a Hungarian Modernist who died in the Holocaust.

Other photographs on view use darkroom alchemy to turn eyewitness events into images of magical realism. In “Scanno” (1957-1959), Mario Giacomelli transforms a familiar scene in his Abruzzo village, located about 60 miles from L’Aquila, the Italian town recently shattered by an earthquake.

In this high-contrast image, the figures of village women swathed in black coats, scarves and hats are blurred, abstracted figures. As they make their timeless procession down the hillside from the town piazza, in the center of the composition, one figure is in sharp focus: a boy who looks straight at the camera. The photograph turns an everyday moment into an image of surprise and even awe — contrasting the eternal, anonymous and unchanging rhythm of life in a town with the verve of one particular boy.

“Photographic Figures” is on view through May 10 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, located at 465 Huntington Avenue. For more information, visit http://www.mfa.org.