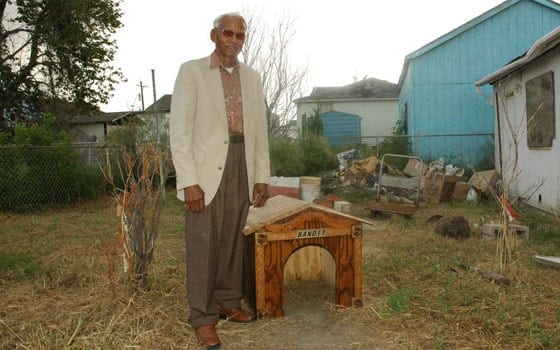

Malvin Cavalier, an 86-year-old New Orleans native, stands next to the doghouse of his dog, Bandit, in this image from the documentary “Mine.” The film, which will be screened during this year’s Independent Film Festival Boston, chronicles the heart-wrenching tales of residents, like Cavalier, who were separated from their pets when they were evacuated during Hurricane Katrina. (Photo courtesy of Geralyn Pezanoski)

Cinephiles willing to tread off the beaten path and check out this year’s Independent Film Festival Boston, running through next Tuesday, April 28, will find insightful, critical meditations on contentious social issues, ranging from an American Indian-led environmental crusade and a human rights-violating dictatorial regime to the human and animal fallout from a natural disaster.

Granted, the topics are heavy. However, the films’ directors, each of whom will be present at screenings and will stay on afterwards for audience QandA sessions, have promised that their movies are intended to provoke thought, discussion and action, rather than depression.

Malcontents, consider yourselves warned: the following films may contain inspirational and/or uplifting content.

The story of “Upstream Battle” can be traced back to the arrival of the Pilgrims — Native Americans vie for the survival of their lands, waterways and ways of life against the more powerful, better funded white men who profit from their exploitation. In the case of the struggle of the tribes and non-native stakeholders living along California’s dammed Klamath River, though, the moral blame of the situation is not so easily delineated, the story not so cut and dried.

At issue is a proposal to dismantle four hydroelectric dams on the Klamath. Electric company PacifiCorp praises the dams as an inexpensive source of climate-friendly energy; tribal opponents claim that the dams have turned the river into a “toxic soup,” killing off tens of thousands of Pacific salmon and crippling tribes’ traditional fishing industry.

Credit goes to German documentarian Ben Kampas for vowing to present the full complexity of the drama surrounding the proposal.

“I didn’t want … a black-and-white story where the film tells people what to think about an issue,” he said.

Still, providing an informative and honest assessment of the situation, while still making it accessible to audiences, proved trying, the director said.

“It was a huge challenge for me from a filmmaking perspective,” he said. “There are 26 different parties in the talks — four tribes, the state and federal government, environmental organizations, PacifiCorps and other corporations.”

Further complicating the matter was the lack of any singular protagonist or antagonist, the kinds of figureheads that form the cornerstone of cinematic convention.

The film does focus on the Native American perspective within the conflict, not only because Kampas said he found their story the most engrossing, but also because “they are a group people know very little about.”

Kampas said he hopes the film will challenge stereotypes about Native Americans, including ones he had picked up in his native Germany

“I had the same stereotypes about Native Americans that most people in Europe have — that they are impoverished, have problems with drug addictions, unemployment, that the luckier tribes run casinos,” he said.

“One thing I learned is the culture [of the tribes depicted in the film] is still very much intact,” Kampas added. “The other thing is that today we so-called white people think that these disadvantaged people need empowerment of some kind. They are really powerful people themselves.”

Another powerful figure lends his name to “Kimjongilia,” albeit indirectly.

The feature-length documentary is named after a flower, which itself was named after — and created via genetic manipulation for — infamous North Korean leader Kim Jong Il. Its title notwithstanding, however, the film is not about horticulture, and its take on North Korea’s authoritarian government is anything but rosy.

In her directorial debut, N.C. Heikin makes use of interviews with dissident North Korean defectors and survivors, which she ironically juxtaposes with archival footage from actual propaganda films.

The result is a rare glimpse behind North Korea’s notoriously secretive iron curtain, one that sheds light on the lives of the more than 22 million inhabitants of a country that we now read about in the news nearly every day, but know so little about.

“I think the audience will be very surprised at the extreme state of totalitarianism in North Korea,” Heikin said. “I think it will be an eye-opener at the extent of human rights abuses.”

The film draws its poignancy from its use of North Koreans’ own testimony to humanize their predicament.

“Most people know Kim Jong Il is an evil and bad dictator, and we know about his nuclear pretensions — and he may indeed be exporting nuclear technology — but we don’t ever hear from people inside,” Heikin said.

Such personal stories are also at the heart of “Mine,” winner of the prestigious Audience Award for Best Documentary at the South By Southwest Film Festival. The film offers a profound, touching insight into the devastation of Hurricane Katrina and its ongoing aftermath, focusing on some of the hardest-hit victims of the disaster — pets and their caregivers.

“Mine” chronicles the heart-wrenching anecdotes of many residents who were separated from their pets, or forced to abandon their beloved companions in their inundated homes or on rooftops, as FEMA rescuers and shelters only made provisions for human family members.

Due to their own resourcefulness and the laudable efforts of rescuers drawn from around the U.S. and beyond — including the film’s director, Geralyn Pezanoski — many of these pets survived the disaster. However, with no way of finding their original owners, many found themselves dispersed to animal shelters across the nation, adopted into new families who were moved by their plight.

But what happens when, months or even years later, the inhabitants of New Orleans are back on terra firma and want their cherished animals back? Who should be the rightful owner — the new families, who have taken in the pet with noble intentions and grown attached, or the original caregivers, many of whom see recovering their pet as a necessary step toward reunifying their families and healing from the trauma of Katrina?

Questions of disparities in wealth, class and race, often noticeable between the new and original caregivers, add another layer of complication to the issue. As Pezanoski noted, it was usually the people who were the most disenfranchised who were least able to evacuate their pets.

“In Katrina, there is no way to avoid questions of race, class and privilege,” she said. “I don’t think in making [the] film that I set out to make a film about [these topics], and I don’t think we ever comment on it, but it comes out in people’s stories.”

The Independent Film Festival Boston runs from April 22, 2009, through April 28, 2009, with screenings at the Somerville Theatre, the Brattle Theatre, the Coolidge Corner Theatre and the Institute of Contemporary Art. For a full screening schedule and more information, visit http://www.iffboston.org.