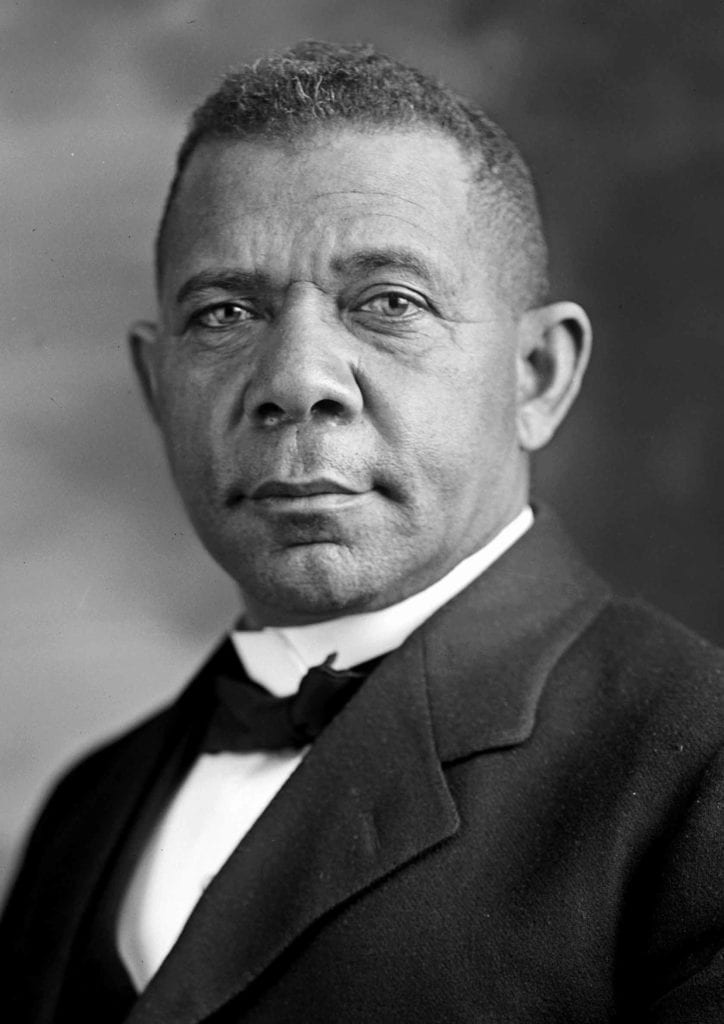

Booker T. Washington’s message to young African Americans in Cambridge

On the night of Sept. 2, 1903, national black leader Booker Taliaferro Washington delivered a short but uplifting address to young black Cantabrigians on the importance of saving, purchasing property and going into business. Invited by then-third Assistant U.S.

District Attorney William Henry Lewis, Washington spoke at Mt. Olive Baptist Church (now known as the Massachusetts Avenue Baptist Church).

It was about 8:30 p.m. on that fair evening when Cambridge Mayor John H. H. McNamee escorted Professor Washington to the podium. According to a local newspaper account, the prominent leader’s reception was most remarkable, “as the greeting was long and hearty, so that several minutes elapsed before he could speak.”

As he stared into a crowd of anticipating faces, the orator stepped forward and said, “I want to speak to the young people, as I see so many bright and intelligent young people here tonight. I am reminded of the superior opportunities that these young people have over mine when I was a child. I was born a slave and am not ashamed to say so.”

Booker T. Washington was indeed born a slave in April of 1856 on a plantation near Hale’s Ford in Franklin County, Virginia. He belonged to James Burroughs, for whom his slave-mother, Jane, was a cook. After the Civil War, Washington moved with his mother to Malden, West Virginia, where he joined his stepfather, Washington Ferguson, who had escaped from slavery. Soon after moving to Malden, Booker T. Washington’s mother died, leaving him to mostly fend for himself, with some help from his stepfather.

Compelled to work as a child, Washington secured a job in the household of General Lewis Ruffner, a salt manufacturer in Malden, who paid him a modest salary and permitted him to attend school during the day. By this means he was able to educate himself.

In 1872, Washington enrolled at Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, from which he graduated in 1876. He returned to Malden to teach school. In 1878, he attended college at Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C. (now Virginia Union University), after which he became a teacher at Hampton Institute, where he remained two years.

The Alabama Legislature passed an act in 1880 establishing a normal school in Tuskegee. Washington was recommended for the job of running the new school. He immediately went to Alabama to organize an institute whose purpose was to train teachers and provide African Americans an opportunity to acquire thorough moral and industrial training.

Humble beginning

In a church and a small shanty with one teacher, Washington formally opened the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute’s doors to 30 students on July 4, 1881. Under his able leadership and with the help of wealthy white philanthropists, the institute (now called Tuskegee University) grew remarkably. By 1915, the campus contained more than 100 buildings, and the school, with a nearly $2 million endowment, enrolled 1,500 students and employed a 200-member faculty who taught 38 trades and professions.

On Sept. 18, 1895, Washington delivered his notorious “Atlanta Compromise” address to a largely white audience of Southerners at the Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition. He told them that blacks should shun politics and learn to dignify and glorify common labor. The professor dismissed agitating for social equality as extremist folly and expressed a willingness to accept social segregation, informing them, “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”

For years, Washington spoke about the need for the industrial training of black men, as he believed it would start the race off on a solid foundation. On this industrial foundation would grow habits of thrift, a love of work, economy, and ownership in property, he thought. He was at odds with such contemporaries as W. E. B. Du Bois over the best way to improve conditions for African Americans: Was the better road for black men one leading to industrial training — to those schools whose purpose was to teach them a trade or to work with their hands — or one leading to college? Du Bois, like Washington, supported industrial training among the masses, but he believed blacks also needed college-educated leaders.

In 1900, Washington co-founded the National Negro Business League (NNBL), of which he became founding president. At its first major conference, held at Boston’s Parker Memorial Hall on August 23 of that year, he announced the organization’s major objectives: to annually bring together those of the race engaged in various branches of business, from the humblest to the highest, for the purpose of closer personal acquaintance and of receiving encouragement, inspiration and information from each other; and to originate plans by which local business organizations could be formed in all parts of the country to serve the best interest of the race. By 1915, the NNBL could boast of more than 600 chapters in 34 states.

When Washington gave his speech at Mt. Olive Baptist Church on that summer night of 1903, he offered black children of Cambridge some practical guidance — much of which is still relevant today. He said, “I hope that you will learn to keep out of debt. I hope that you will have the strength of character not to lead your parents into the purchase of things which they are not able to own. I made up my mind to do something, to build something for the race and not to spend my time talking about what I intended to do. The world only cares about what the individual is doing.”

Mindful that the employment options for young black men were limited then, Washington advised them, “Make up your minds to go into business, start something, stick to it, and success is yours. Don’t mind what the other fellow is doing, as you cannot attend to your business and his, too. In this country we have got to have a certain amount of material possession for the fundamental growth of our race, or we shall be left behind.”

Washington saw hope for the future in the faces of the young, and he thought they’d be put on the road to independence by saving regularly and purchasing property. He told them, “Resolve from tonight to turn over a new leaf; start a bank account, begin to save to buy property, get your own homes, and build yourselves up strong in your community.”

The national leader understood that building a strong economic base wouldn’t be easy, so he advised, “You will have to make some sacrifices, but be yourself. Do not become discouraged because you are black and poor and think there is no future for you. There are yet opportunities for all, and what the whites have accomplished, so too can we if we have faith in ourselves. Be honest, even if you are poor.”

Washington wrote five books, the most popular one being his autobiography “Up from Slavery” (1901). He also served as an adviser to Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. An influential educator who was considered black America’s greatest turn-of-the-20th-century leader, Booker T. Washington died in Tuskegee, Alabama, on Nov. 14, 1915.