Known as the Judge’s son, Keith Elam would change the hip hop industry as the legendary Guru – but he had to convince his parents first

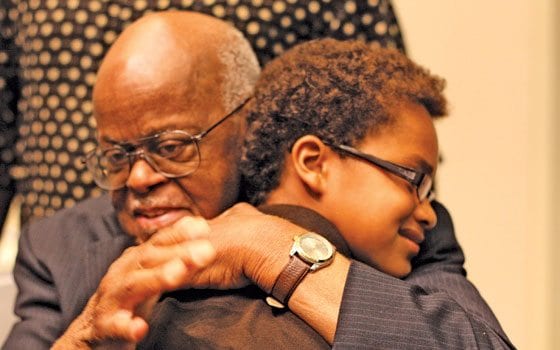

Keith Cassim Elam, son of the late legendary hip hop artist Keith “Guru” Elam, hugs his grandfather Judge Harry J. Elam Sr. during a memorial service held at UMass/Boston Sunday, July 18, 2010. (Enesto Arroyo photo)

| In the top photo, trumpet player Nick “Brownman” Ali plays a little jazz before celebrating the life of legendary rapper Keith “Guru” Elam during a memorial service at UMass/Boston last Sunday. Guru’s nephew Justin Ruff, his brother, Harry Elam Jr. and cousin Russell Clark take a break for a moment. In the bottom photo, (l – r) pioneer Roxbury Rapper Ed O.D., DJ Moe D of Hot 97 and Lino Delgado, founder of the legendary bboy group the Floorlords, joined hundreds who paid their respect to the late Keith “Guru” Elam last weekend at UMass/Boston. (Ernesto Arroyo photos) |

It was early in the rap game, back when lyrics were raw and the MCs outlandish, and, for the first time in his life, Big Shug was reluctant to go onstage: “I was like, ‘I don’t know, man.’ ”

The reluctance was understandable. But his partner, Keith Elam, was persistent, begging and pleading with Shug to do this one set — and things would be alright. If successful, Elam exclaimed, they would be able to pursue their dreams of making it big in the music business.

And off they went to perform their act before two people — Elam’s equally reluctant parents.

Distinguished attorney Harry J. Elam Sr., the first African American to preside as a judge in the Boston Municipal Court of Massachusetts, and his wife, Barbara, a noted educator and former director of the library system for Boston’s public schools, was part of the dignified Roxbury, the one where success was more than a goal. It was expected, and in fact, demanded of the heirs of those who had achieved.

Rap, hip hop — whatever it was called at the time — was not part of that discussion. “I thought I was going to be guilty of something,” Big Shug recalled. “But we did it, right there in his parent’s living room. And Guru was so happy that he kept telling me how much that meant to him and how he appreciated what I had done.”

Guru was right about one thing. For Big Shug, who grew up in Mattapan and would later run afoul of the law, he never feared performing before another crowd. “I think that was one of the toughest things I have ever done,” Big Shug said.

That story was shared with several hundred people gathered at UMass Boston last Sunday to celebrate the life of Keith Elam, the legendary musician who went by the name of Guru. Last summer Guru was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a form of cancer.

In February he was taken to the hospital after suffering from related respiratory problems and soon afterwards slipped into a coma from which he never recovered. He died in April at the age of 47.

“He died too soon,” Judge Elam told the gathering. “But he had been in a coma for a while and he would not have been the same Keith.”

It was dignified crowd of lawyers and rappers, family and fans — most with a connection to Roxbury, from Ed O.G., arguably one of Boston’s most renowned rappers to Willie Davis, the esteemed criminal defense attorney who kept a young Keith Elam focused during his days at Morehouse College.

Davis, a Morehouse man himself, told the story of Dr. Benjamin Mays, the former president of the all-male, historically black college in Atlanta. According to Davis, Mays once talked about the “air of expectancy,” where Morehouse men were expected to do well, and upon graduation to do exceptionally well and that he expected nothing less.

By all accounts, that message was not lost on a young Elam. In fact, success was already deeply rooted in his DNA. It just took a little time — and patience.

But spitting rhymes?

Even now, Judge Elam can only shake his head. His youngest son was the rebellious one, unable to flourish in a world of vigorous academic study and intellectual discipline.

“I would hesitate to tell people what he was doing, because I didn’t feel that good about it myself,” Elam once told the Boston Globe. “I used to say, ‘He’s in music,’ but I would never specify rap. When he said that this is what he wanted to do, I was very unhappy, to be totally honest. Why would he want to waste his time doing this rap thing? I just couldn’t see it. I have to admit that I was wrong. I made an improper judgment at that time. But I’ve come a long way.”

Judge Elam did the best he could. He and his wife tried. They sent Keith to the prestigious Noble and Greenough School but that didn’t work as planned. “Keith wasn’t like his older brother who was an ideal student, class president and graduated with honors,” Elam said. “Keith wanted to be his own person.”

Keith’s older brother, Harry Elam Jr. went on to Harvard and became the Olive H. Palmer Professor in the Humanities at Stanford University. A recognized authority on black theater, Elam is now Vice Provost at Stanford.

But the next stop for Keith at the time was as a Metco student at Cohasset High School. Quite naturally, the Elams received telephone calls from school officials every now and then informing them that Keith wasn’t in school. His mother knew where he was hanging out and would go to those spots, pick him up and drive him to Cohasset.

He graduated on time, as he did at Morehouse. But the last straw with his family came when he boldly pronounced that he wanted to attend a two-year fashion school in New York City.

Judge Elam was not happy but helped finance the education anyway. When Keith returned home after the first year, explaining that he no longer was interested in fashion, Judge Elam had heard enough, informing his baby boy that he would now be on his own.

It was probably the best thing that ever happened.

“You have to go for yours,” Keith would later advise young rappers. “Nobody is going to do it for you. My father used to say that all the time, but I never really learned that until I was out on my own. That’s one thing a lot of young brothers have to learn for themselves.”

Keith learned that lesson first hand. With his neighborhood partner, Big Shug, Elam initially performed in suburban talent shows and Boston clubs such as Chez Vous in Dorchester and the now-defunct Lanes Lounge in Mattapan.

But Guru’s quest for recognition came to a halt in Boston. He decided to move to Brooklyn, the heart of hip hop. The road was tough, but a break occurred when Guru teamed up with Christopher Martin, known as DJ Premier. They signed to Wild Pitch Records and, in 1986, debuted their first album, “No More Mr. Nice Guy.”

Later the pair dropped hits such as “Code of the Streets,” “Mass Appeal” and “DWYCK.” In all, they released six albums between 1989 and 2003 that were both critical and commercial successes.

“Step in the Arena” (1991) is considered a high-water mark in the genre, according to one reviewer, “as it combined Guru’s brash rhymes — filled with braggadocio, humor and social critiques — and the inventive, often jazz-laced tracks provided by Premier.”

Gang Starr’s fifth album, “Moment of Truth,” hit number one on the Billboard RandB/hip hop album charts. Along with artists such as Public Enemy, De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest, Guru helped make the late 1980s and the 1990s what Rolling Stone magazine called “Rap’s golden age.”

“Rap is way more than violent noise, which is what some people think,” Guru told an interviewer. “I’m here to demonstrate that. The philosophy of taking control of your life comes out in my lyrics because it’s what happened to me. There’s purposely no cursing, because it’s relating to and having respect for other generations.”

That respect came in part from Roxbury in general and his godfather in particular.

As a solo artist, Guru released a quartet of critically acclaimed “Jazzmatazz” albums from 1993 to 2007. Those albums, each with a different musical slant and subtitle, found the artist working with a wide variety of artists including jazz greats Branford Marsalis, Lonnie Liston Smith, Roy Ayers, Bob James, Donald Byrd, Herbie Hancock; RandB stars Erykah Badu and Macy Gray, and fellow hip hop artists Common and the Roots.

The jazz connection was learned at an early age. His uncle George Johnson, the one-time headmaster of English High School, played the greats for his nephew.

“Every time I would go to my godfather’s, he would make me sit down in his living room and listen to John Coltrane, Charlie Parker and Sonny Rollins,” Guru said. “When the Jazzmatazz concept first began, nobody had really thought to put hip hop and live jazz together. Now, all these years later, I stake my claim as the father of this genre.”

One critic who flew in from India to attend Sunday’s tribute agrees. Carolyn Martin wrote for Soul Underground, a British hip hop magazine, and was quite impressed with Guru when she first met him in the early 1990s.

“It was his degree of inner silence,” she said. “He was almost too serious, too reserve for the world of ultra-macho MCs. He was introspective, an intellectual and extremely disciplined. He was larger than self-promotion because his music wasn’t about himself.”

Guru had that rare ability to transform his music into an art form that even the reluctant ultimately embraced. Two such fans were his Dorchester neighbors. Still reluctant to call him Guru — we knew him as Keithy — Dr. Nancy Norman, the chief medical officer at the Boston Public Health Commission and her sister Patricia Green, the marketing director at Student Funding Group LLC, a New York-based college financial aid company, said they both were not fans of rap and its disrespectful language and depiction of women.

“It took me awhile, Green said. “I never liked the genre — until Jazzmatazz, the fusion of jazz and hip hop. I thought to myself, ‘Now, this makes sense.’ And I think that is Keithy’s legacy. He had the ability to merge different genres.”

And drop knowledge. Ask his nephew Justin Ruff, an aspiring actor now living in Los Angeles. Ruff said he looked up to his uncle in part because he had few older men in his life. “He taught me various things about life; he instilled wisdom,” Ruff said. “He always told me ‘Never put the two before the one.’ What that meant was never put anyone else before yourself. I carry that with me to this day.”

By all accounts, Guru was a man of honor. As Big Shug tells the story, he and Guru had several falling outs during their life-long friendship but remained tight.

“The one thing we said to each other was that if one of us makes it, and the other doesn’t, the one that made it will help the other,” Shug said. “And that’s what Guru did. He reached back for me and helped me out. He was a man of his word.”