Remembering the other Eartha Kitt

The smile on Eartha Kitt’s face was unforgettable. It belied the pain, ridicule and turmoil that she had endured after she was unceremoniously shoved at or near the top of then-President Lyndon Johnson’s enemies list.

But that seemed to be the furthest thing from her mind on one afternoon, late in the spring of 1978, when she greeted me at the old Aquarius Theater in Hollywood.

Kitt was in Los Angeles starring in her touring production of the musical “Timbuktu.” I was assigned to do a brief interview and a review of the production. Her smile and infectious energy melted the awe and nervousness that I felt at being up close to — not to mention actually talking with — an entertainment legend.

Then there was the “incident.” That was the furor that Kitt ignited when she denounced the Vietnam War and poverty in the U.S. to Johnson at that White House luncheon in January 1968. A decade later, mention of the controversy still got tongues wagging.

Her performance in Los Angeles was, in part, Kitt’s rehabilitation on the American entertainment scene after being virtually banned in the U.S. following her White House outburst. Her performance was also a brash effort to reclaim the luster that had made her a household name and an icon in the entertainment world of the 1950s and early 1960s. By then, Kitt had firmly established her legacy as an award-winning internationally acclaimed singer, dancer and actress in films, on the stage and on television. She was tagged as sultry, sensual, sexual and alluring.

But that was the surface stuff. Kitt’s brash, sassy and high-energy style sent the clear message that she was her own woman. She refused to be relegated to stereotypical stage and film roles, turning her sensuality into a badge of fierce independence and pride, a trademark of defiance. Her pioneer independence and sense of self would influence later generations of young female entertainers, from Oprah to Madonna to Beyoncé. They owe her a debt of gratitude.

But even that side of Kitt obscured the woman who was passionately devoted to and supported peace and civil rights causes. The clash with Johnson — really, with the Johnsons, both the president and his wife Lady Bird Johnson — at the celebrity women’s luncheon in January 1968 gave the first public hint of that.

Lady Bird Johnson had invited Kitt to the luncheon and, in an innocent moment, asked Kitt what she thought about the problems of inner-city youth. Kitt didn’t mince words and lambasted the Johnson administration for not doing more about poverty, joblessness and drugs in black communities. And she didn’t stop there — she tied her outburst directly into an attack on the Vietnam War, which she said the U.S. had entered without reason or explanation.

Kitt’s verbal assault on the war and the country’s racial problems made headline news. A badly shaken first lady and an enraged LBJ denounced her. Over the next few years, she was hounded and harassed by the FBI, the IRS and Secret Service agents. The CIA even compiled a gossipy, intrusive dossier that attempted to paint her as a sex-starved malcontent.

The public storm and the negative press proved to be too much: Kitt’s career was effectively dead in the United States. But she stuck to her guns and did not apologize, retract or soften her criticism of Johnson’s conduct of the war or his racial policies.

In fact, she hadn’t said anything at the luncheon that thousands of others hadn’t said about Johnson’s hopelessly failed, flawed and losing strategies. The difference was who said it (namely, a celebrated star) and where it was said (at the White House). Kitt took the heat and paid the price for giving an honest opinion and remaining true to her deeply felt beliefs about the cause of peace and social justice. For this, she was branded as a racial agitator.

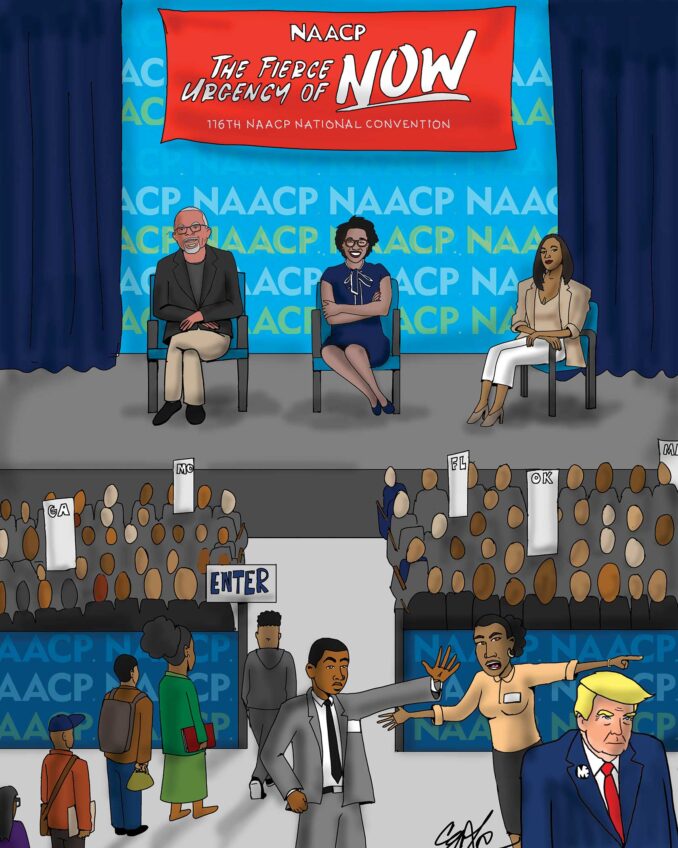

Missed in the overreaching hysteria and the vindictive bashing were the facts that lay beneath Kitt’s glittery, carefully crafted sexpot image — that she had given time and money to the NAACP and other civil rights organizations; that she had supported and participated in the March on Washington; that during her “wilderness years,” when she was forced to work outside the U.S. and took heat for performing before all-white audiences in South Africa, she broke barriers by insisting on an integrated cast and quietly raising money for black schools in the country.

During our brief talk before her stage performance in Los Angeles, Kitt spent as much time talking about her devotion to the civil rights movement and the injustice of apartheid in South Africa as she did about the production in which she was appearing. She did not mince words when I gingerly asked her about the “incident.” She laughed, but did not express any regret about what she said and did that day at the White House. She expressed no bitterness about the years of media and public ostracism.

This impassioned contributor to the struggle for peace and civil rights — this is the Eartha Kitt that I knew, and that I now remember and pay homage to. As she famously sang, “C’est si bon.”

Earl Ofari Hutchinson is a syndicated columnist, author, political analyst and social issues commentator.