As we gather to celebrate Juneteenth, it is vital to reflect deeply on the historical context surrounding the delayed emancipation of enslaved people in Texas. Juneteenth commemorates June 19, 1865, when Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston announcing the enforcement of President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, issued more than two years earlier, on January 1, 1863. This gap between the official end of slavery and its enforcement in Texas illustrates the enduring struggle between federal authority and what would later be framed as “states’ rights.” This dynamic notably intensified during the Centennial Scandal of the presidential election of 1876, profoundly shaping America’s political and social landscape.

The delayed freedom of Texas slaves reveals much about the fragile nature of legal authority when confronted by entrenched social resistance. The Emancipation Proclamation legally ended slavery in Confederate states; however, enforcement depended heavily on the Union Army’s physical presence. Texas, geographically remote and lightly occupied by Union forces, became a haven for slaveholders fleeing stricter enforcement elsewhere. Slaveholders took advantage of the ambiguity and the absence of federal enforcement, maintaining their economic and social dominance through continued exploitation. Thus, enslaved people in Texas lived in limbo, their freedom officially granted but practically denied.

This dynamic resurfaced powerfully a decade later in the controversial presidential election of 1876, often referred to as the Centennial Scandal. The fiercely contested election between Democrat Samuel J. Tilden and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes exemplified deep national divisions rooted in unresolved tensions from the Civil War. Tilden secured the popular vote by approximately 250,000 votes and held 184 electoral votes, needing just one more to win. However, disputes arose over 20 electoral votes from Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina and Oregon, all of which involved allegations of fraud, voter intimidation and ballot manipulation.

To resolve the impasse, Congress formed the bipartisan Electoral Commission composed of five members each from the Senate, the House of Representatives and the Supreme Court. The commission ultimately awarded all disputed electoral votes to Rutherford B. Hayes, a decision made strictly along party lines. The outcome sparked outrage among Democrats, risking a severe political crisis.

The situation compelled both parties to negotiate secretly, culminating in the Compromise of 1877. Democrats agreed to concede the presidency to Hayes under specific conditions, which had dire consequences for Reconstruction and the fight for civil rights. Key among these conditions was the Republicans’ promise to withdraw all remaining federal troops from Southern states, effectively ending Reconstruction.

This decision drastically reasserted the principle of states’ rights, allowing Southern states to govern themselves without federal oversight. While couched in the language of political compromise, this essentially sanctioned Southern states to undermine civil rights legislation. Texas, among other Southern states, seized this opportunity to impose Jim Crow laws, disenfranchisement and institutionalized racial discrimination, reinforcing systemic inequality that would endure for nearly a century.

The principle of states’ rights was thus weaponized to resist federal mandates on equality and civil rights. Southern states argued that their rights to legislate independently superseded federal attempts to guarantee civil liberties. Texas and other states leveraged this principle to resist enforcing equal rights, employing legal maneuvers, intimidation and violence to maintain white supremacy.

The Compromise of 1877 had profound implications. Reconstruction had aimed to integrate formerly enslaved people into the civic and political life of America. However, its premature end allowed for the resurgence of white supremacist power structures across the South. Texas, like other Southern states, implemented poll taxes, literacy tests and violent intimidation to disenfranchise Black voters. Segregation laws institutionalized discrimination, perpetuating the social and economic subjugation of African Americans.

This historical regression was mirrored recently in 2013 when Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts issued a controversial decision in Shelby County v. Holder, which effectively reversed key provisions of the 1964 Voting Rights Act. Roberts argued that conditions had sufficiently improved, rendering federal oversight of state voting laws unnecessary. This decision critically weakened protections against voter suppression, resulting in numerous states enacting restrictive voting laws that disproportionately affect minority communities. Roberts’ ruling reflects a troubling repetition of history where states’ rights rhetoric masks systemic efforts to undermine civil rights and racial equality.

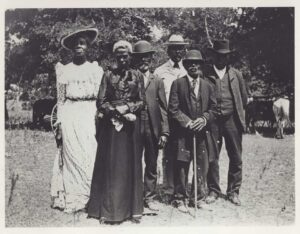

Photograph of Emancipation Day celebration, June 19, 1900 held in “East Woods” on East 24th Street in Austin. Mrs. Grace Murray Stephenson also kept a diary of the day’s events which she sold to the San Francisco Chronicle which reported a full-page feature on it. PHOTO: GRACE MURRAY STEPHENSON /LIBRARY OF TEXAS

As we celebrate Juneteenth, remembering the long delay between legal emancipation and practical freedom serves as a reminder of the critical importance of enforcement in upholding civil rights legislation. Freedom without effective enforcement is illusory, as history repeatedly demonstrates.

The Centennial Scandal exemplifies how political compromise at the expense of civil rights can have enduring negative impacts. By empowering Southern states through the withdrawal of federal oversight, the Compromise of 1877 enabled nearly a century of legalized discrimination, violence and social injustice. The fight for civil rights, equality, and justice continued well into the 20th century and remains ongoing today.

Juneteenth thus symbolizes both liberation and the ongoing struggle for true equality. It reminds us that official proclamations of freedom and equality are insufficient without robust mechanisms for their enforcement. The holiday underscores the necessity of vigilance in protecting civil liberties against the constant risk of erosion through political compromise or neglect.

Today, as America reckons with its historical and contemporary racial injustices, Juneteenth serves as a poignant reminder of how easily freedoms can be compromised. It calls for continued commitment to dismantling systemic racism and advocating policies that ensure equity and justice for all Americans.

Juneteenth’s historical roots and the implications of the Centennial Scandal and Roberts’ decision teach us that civil rights and equality require more than legislative victories; they require vigilant enforcement and persistent advocacy. The struggle for genuine freedom is ongoing, requiring sustained efforts to uphold civil liberties and confront injustices head-on. As we commemorate Juneteenth, we honor those who fought for freedom and recommit ourselves to the unfinished work of building a truly equitable society.