Surprises await those who think they know M.C. Escher from the endless reproductions of his works on posters, ties, T-shirts and other paraphernalia. The Museum of Fine Arts Boston exhibition, “M.C. Escher: Infinite Dimensions,” on view through May 28, presents works by the Dutch printmaker from the 1930s through the ’50s that tell a richer story of Escher and his inventiveness.

An image by Maurits Cornelis Escher (1898–1972) can prompt the question: Is this art or a clever visual feat? Fans of Escher abound among mathematicians and scientists, and it’s not difficult to understand why: His ambitious optical games often embody mathematical principles and invite analysis.

Drawn from public and private collections, all 50 images on view in the MFA’s fascinating exhibition stir visual delight, and some inspire wonder. A few possess a magnetism that engages more than a cerebral response. In their repetitive, rhythmic patterns, they provoke awe and mystery and evoke the very metamorphosis of life—an achievement that goes well beyond the scope of a clever visual game.

Organized by Ronni Baer, an MFA curator, the exhibition fills two large galleries connected by a central kiosk with angled walls that reflect the geometry within the works on view. Escher was a bravura printmaker, and his works include lithographs, woodcuts, mezzotints, linoleum cuts, and wood and metal engravings along with a few watercolors and drawings. Most are in a palette of white, black and gray, but a few include colors, mainly maroon and the pale green of young plants.

Early career

After attending architecture school, where a teacher encouraged him to pursue printmaking, Escher lived from 1922-1935 in Italy, married and raised a family. Troubled by the rise of Fascism, he and his family left Italy, and by 1941 he was back in Holland.

M.C. Escher, “Day and Night” (1938). Photo: Susan Saccoccia

Escher let observed reality into his early works, which include scenes of Italian hill towns. The earliest and most poignant images on view are his lithographs “Ravello and the Coast of Amalfi” (1931), and next to it, “Still Life with Mirror” (1934), an introspective close-up of personal grooming items on a dresser and, in its mirror, a reflected view of the narrow hill town street outside.

Inspired by a visit to the 14th-century Alhambra palace in Granada, Spain, where he admired the intricate, repetitive patterns of interlocking shapes in its Islamic mosaics, Escher adopted the technique, known as tessellation.

In 1936, he began a multi-decade series of prints exploring tessellation, entitled “Regular Division of the Plane,” replacing the abstract shapes of the Islamic tiles with the silhouettes of creatures, such as birds and fish.

The earliest example on view of these experiments is his hallucinatory woodcut “Day and Night” (1938), in which identical, interlocking black-and-white silhouettes of birds take form in relationship to one another, like pieces in a puzzle. Later examples from the series show winged dogs, frogs, beetles and chess figures.

Organized to highlight Escher’s various visual preoccupations rather than by chronology, the exhibition provides excellent wall texts and pairs many images with comments from Escher fans in various professions. Ian Hunter of the rock band Mott the Hoople confesses that he put Escher’s 1943 lithograph “Reptiles” on the cover of the band’s 1969 debut album without seeking permission.

Metamorphoses

A dazzling composition of tessellations is at play in Escher’s hexagon-shaped lithograph “Verbum” (1942). At its center is the work’s title, Latin for “word,” evoking the opening lines of the Book of

M.C. Escher, “Puddle” (1952) Photo: Susan Saccoccia

Genesis, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” Radiating from the center, triangles morph into birds, fish and frogs, representing divine creation of sky, water and earth. Seemingly in flight from their earlier appearance in his 1938 woodcut “Day and Night,” two waves of black and white birds converge and cross, suggesting the balance between darkness and light.

The astonishing “Metamorphosis II” (1939–40) shows Escher using tessellation as a storytelling device. Starting from the left, the 13-foot woodcut, produced from 20 blocks, follows the smallest and simplest of shapes, tiny cell-like figures, as frame by frame they evolve into reptiles, bees and flying insects that in turn change into fish that then become birds. Cubes sprout into an Italian hilltop town, a symbol of human life, but its tower becomes a chess piece.

Endless motion

Escher’s narratives are endless, repetitive loops that keep going without stopping or leading anywhere — like a spinning hula-hoop, but unlike life. In “Reptiles,” the print borrowed by Mott the Hoople, a two-dimensional lizard wriggles out of a drawing as a three-dimensional figure, scales a zoology book and a polyhedron-shaped desk ornament, snorts in triumph, and then heads downhill to rejoin the drawing.

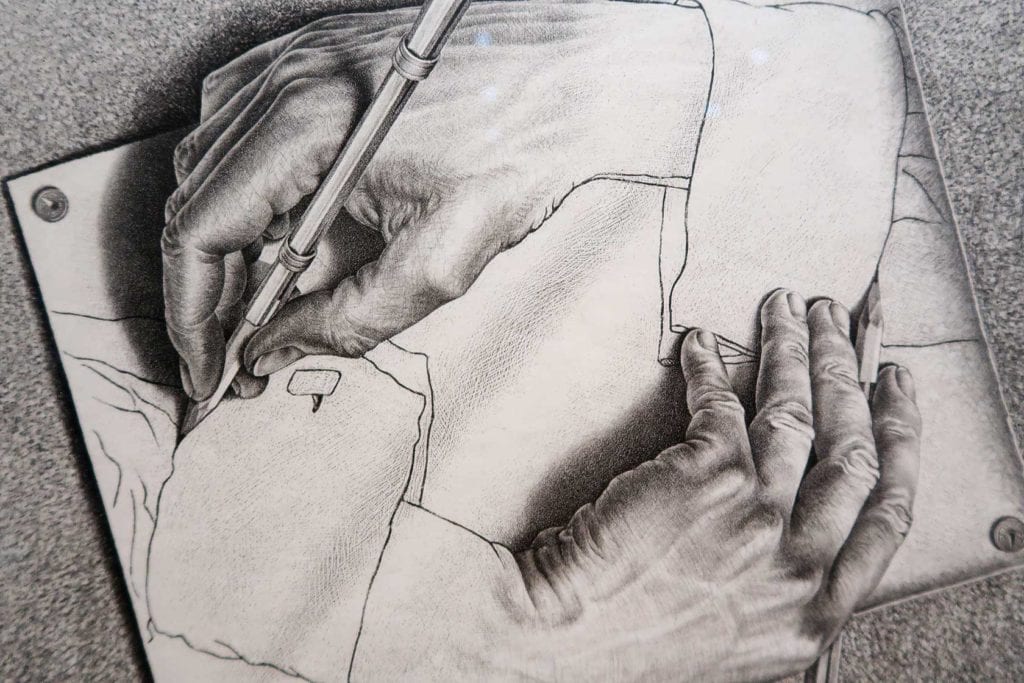

Two lithographs of endless motion are somewhat autobiographical: in “Drawing Hands” (1948), two hands holding pencils form a yin yang cycle; and in “Bond of Union” (1956), Escher portrays a man and a woman out of a single, unending ribbon molded to illustrate their facial features.

M.C. Escher, “Reptiles” (1943) Photo: Susan Saccoccia

Another series renders landscapes and structures as if seen all at once from the front, overhead, and below. Closely related are Escher’s images of impossible buildings, which mingle interior and exterior views. Reflecting on such a structure in his wall text comments, architect Graham Gund finds in its multiple, irreconcilable perspectives a reflection of our times.

Always in step with his own muse — the power of design to tell its own story — Escher worked with an outsider artist’s monastic single-mindedness. Yet, observed reality and human figures return in later works. In a trio of elegant prints from the late ’50s that render the reflections of moon, trees, and sky on water, Escher finds forms in nature.