New perspectives on Black History from WriteBoston’s Teens In Print program — week 2

This Black History Month, the Banner is teaming up with WriteBoston’s Teens In Print program, highlighting young voices of color. Each week, we will feature the work of three new students, who will deliver their perspectives on Black History and what it means to them.

The overlooked history of Black Bostonians

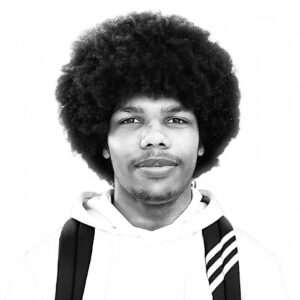

by Gloria Ekechukwu

When I scroll my For You page on TikTok, oftentimes I’m greeted with a TikTok about Boston, and it always shows the same areas and topics that have been heavily discussed before. Whether introducing new, expensive dining options in Back Bay or shedding light on tourist spots in and around Boston. It’s been a common theme for proclaimed “Bostonian” TikTokers, to portray a crafted image of the city. This image is widely accepted by anyone outside of Boston and adopted as an accurate portrayal. Beacon Hill is a neighborhood in Boston known to be on the tourist bucket list. However, the same neighborhood praised for its intricate architecture and importance to the historical map of Boston has a crucial piece of its history hidden: it was once a Black neighborhood.

During the early 1600s, English colonists began their settlement in Boston and in 1635 a beacon mounted on a hill was used to warn settlers in the countryside of danger. This beacon was soon regarded as Beacon Hill and Thomas Hancock, the uncle of John Hancock, established the first home in the area. During the Revolutionary War, British troops overtook Beacon Hill, prompting the evacuation of British troops from the neighborhood and a postwar revamping of Beacon Hill. Boston architect Charles Bulfinch took part in the reconstruction of the neighborhood transforming Beacon Hill into a place where Boston’s richest and most powerful residents resided. This part of Beacon Hill was regarded as the southern slope and overshadows the historical backgrounds of the western and northern slopes of the neighborhood.

While the southern slope is renowned for its prominent wealth and power, the western and northern slopes were homes to working-class families, notably African Americans. Hidden in this side of Beacon Hill was a strong and tight-knit community of middle-class and African American Bostonians who exemplified progressive changes that helped set precedents in the city and the country. It’s in these areas that one of the first integrated schools in the United States could be found. Also, prominent abolitionists and activists lived there, such as Maria W. Stewart, Lewis and Harriet Hayden and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin. Also located in Beacon Hill is the African Meeting House, built in 1806, which is the oldest surviving Black church in the U.S. The African Meeting House served as a meeting space for the Black community in Boston and played an important role in the Underground Railroad and abolitionist movement. The building was used to house enslaved people who escaped through the Underground Railroad. Notable activists including Frederick Douglass congregated there to hold meetings and space for discussion and advocacy. In addition to being an important building for political and social progression, it also was a valuable resource in education for both young and adult African Americans in the early 1800s.

Historical awareness is important and today, the stories of the Black community in Beacon Hill are often swept under the rug on social media. On TikTok, many creators focus on the southern slope of Beacon Hill and often forget the significance that the northern and western slopes have on Boston’s history. Beacon Hill has been reduced to a tourist attraction for its colonial architecture and overpriced food spots, rather than a place for the celebration of Black American determination throughout the 1800s. This lack of coverage of an important part of Boston history on social media is frustrating to me as a black Bostonian as it feels as though Black American history is, in a sense, being gentrified by new-wave influencers. While not talked about much, concealed in that area is the Museum of African American History located on Joy Street. The MAAH offers locals and tourists an interactive telling of Black American history in the city and sheds light on the stories of the people who lived on the northern and western slopes of the neighborhood. The museum acts as a way to preserve the history of the Black Bostonians who lived there, leading to more people being exposed to underrepresented parts of Beacon Hill’s history.

Beacon Hill serves as an unintentional commentary on how much of the historical importance of Black Bostonians is treated. While there are many beautiful landmarks and places that tourists crowd around to marvel at, many seem unwilling to peer into the stories of those not highlighted by the city’s brochures. This unwillingness continues to shed light on the city’s history equally, allowing for the abandonment of groups intertwined in the city’s foundation.

The erasure of the historical significance that Black Bostonians, especially on social media, is the result of historical neglect. Although African American activism and progress have roots in Beacon Hill, yet this is rarely talked about. Rather, it’s portrayed as a historically white, affluent neighborhood. Shining light on the importance of African American history in the city isn’t just about adding context, it’s also about ensuring that the stories of those who have been forgotten are heard. Beacon Hill represents the cultural diversity seen in many parts of the city, and promoting Boston’s cultural diversity to the mainstream is presenting a more accurate tapestry of the city. One that isn’t portrayed on social media.

Gloria Ekechukwu is a teen writer based in Boston who enjoys writing about all things entertainment and niche. She spends her free time watching movies/shows, playing video games, and reading books she’ll never finish.

Why the word “woke” is a dead name for Black People

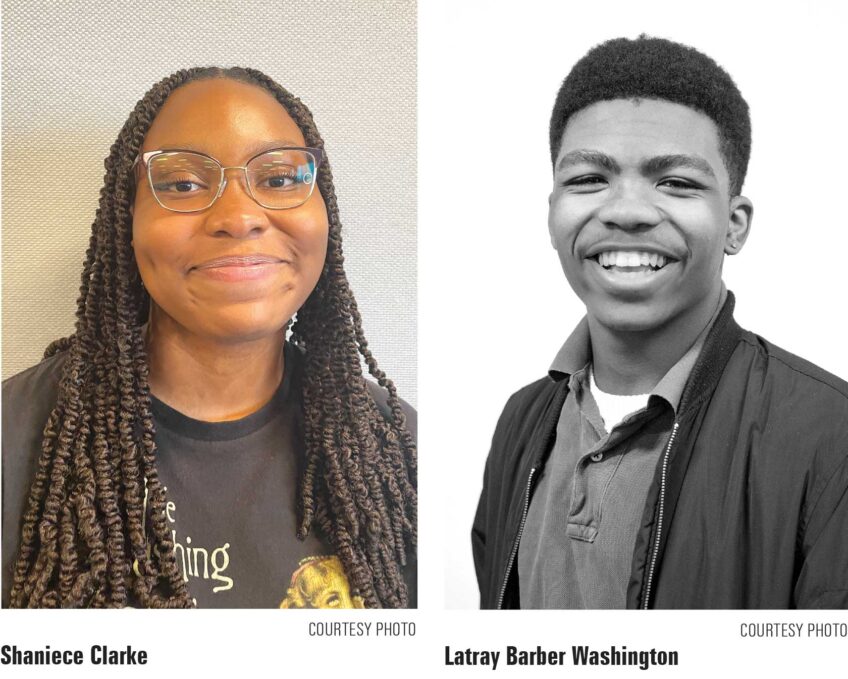

By Mya Bentick

The word “woke” has existed in the Black community for years. Created by Black Power movements dating to the 1930s, Black revolutionaries have defined the term as the action of Black people being conscious of the truth and not being under a distorted reality. To be woke is to be interpreted as being awakened from the slumber of mental slavery many Black people across the world are still under.

The word woke itself is unique, one of the reasons being that this word, like others, is only designated for Black people. This word exclusively applies to us and no other people due to our experience with oppression. Today, non-Black people who assume they have the right to adopt the term overlook its true context and purpose. Non-Black people who use woke because it embodies the process of being radically aware of the society we all live in is not only misused, but is condemned by Black revolutionaries, including myself.

With this word being so bastardized in the modern day, it tends to get tossed around in weak punchlines by those who mock Black people in online chatrooms for the reward of a dry laugh from peers. Viewing the current use of the word, it is used in the mockery of Black people by other races, politics, alt-right white supremacist groups and a handful of Black people who say they’re for the people but really aren’t. Altogether, the word has been taken away from its original meaning, leaving most Black people without the knowledge of its profound significance and misusing it. But how did a word with such meaning become a signal word for facades of proclaimed revolutionaries and essentially become a dead name to Black people? Well, the short answer is white people, but once again, this answer is more complex than you may think.

Woke is a participle adjective and a part of AAVE (African American Vernacular English), often misused by different demographics. As I defined it before, woke is the action of Black people being conscious of the truth. The definition of woke can be understood as the beginning of a revolution inside the brain that manifests into reality. In the origin of this word, examples of how woke is used correctly are in the Black revolutionary perspective. An example of how this word is used correctly is from the 1970s play “Garvey Lives!” written by Barry Beckham. Beckham writes: “I’ve been sleeping all my life. And now that Mr. Garvey done woke me up, I’m gon’ stay woke.” In the line, the word is used to describe the action of being woke and shows the remaining woke state the person is in from learning about Marcus Garvey, a Black revolutionary who in the early 20th century was a leader in the creation of the Pan-Africanist movement. Along with the grammatical correctness of the word is the connotation of it, too. With the purpose of woke being exclusive to Black people, it creates the additional meaning, which is only to be applied to Black people who have unlearned white supremacy and adopted an emancipated mindset. Anything outside that given definition is incorrect.

Now that there is an idea of how woke is used correctly, here are some examples of how it is misused. In politics, where non-Black people are describing people who are Democratic or Republican as woke because of some sort of radical awakening, is automatically incorrect. When a Black person claims that a non-Black person is woke for being aware of social injustices is erroneous. Self-proclaimed Black revolutionaries who participate in the division of the Black community, claiming themselves as woke, are flawed and in denial. And lastly, racist echo chambers where white supremacists use this term to differentiate different types of white supremacists based on how woke they are, and mocking Black people with this term, will always be incorrect. The word woke was never meant for such loose interpretation and to be open just for anybody to use. Woke only applies to Black people who are legitimately woke.

Time and time again, woke is misused by Black people who do not know about Black revolutionaries and non-Black people and chose to take the term and run with it. When Black revolutionaries used this term, it was much deeper than waking up from the lies you’ve been told throughout your history. It was also the beginning of a non-televised revolution that birthed many leaders in the Black community. Part of the reason why Black people are misinformed about this word is because of not being taught about Black revolutionaries in school and instead, being educated on their oppressors. This allows pro-Black thought by revolutionaries to be untaught and misinterpreted by the masses. As for other non-Black people, no amount of education can stop them all from dragging the word through turmoil and erasing its original meaning. Woke for me, however, will always be a word of resilience in a world of oppression, being free from all restraints against me and those who look like me.

In the future, if Black people as a collective want words like woke to be protected and not killed by the abuse of those who do not look like us, our energy should be geared toward educating ourselves instead of those outside of our community so we can work to preserve our ways of effectively communicating with each other.

Mya Bentick is a talented youth writer, reporter, and intern born and raised in Boston. With a passion for writing, she thrives on telling stories that inform, and provoke thought to her audience. Her writing often explores social issues, and entertainment, through her unique perspective as a young Black Caribbean American woman and enjoys reimagining the society we live in.

Journalism as the 4th branch of government

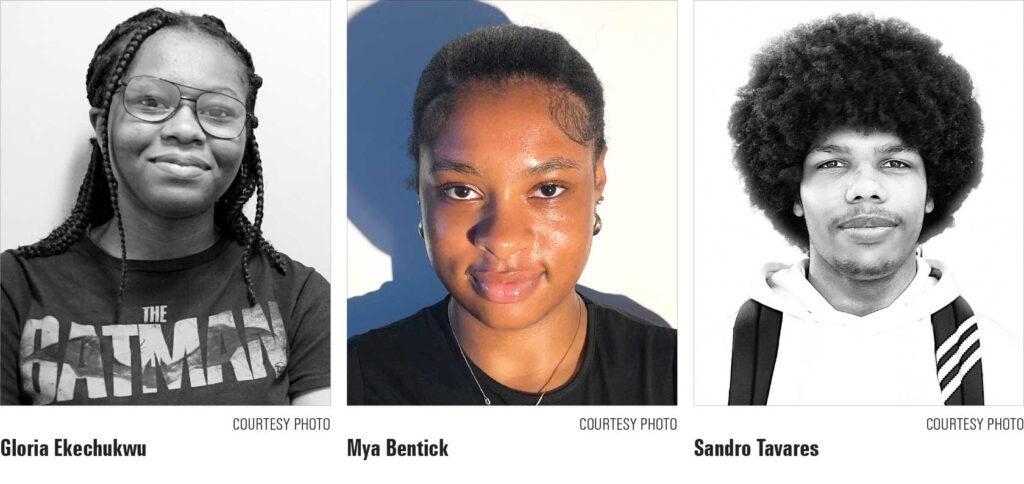

By Sandro Tavares

There have probably been times when you’ve learned something about someone that’s given you a newfound appreciation for them, whether that be a story about your parents from before you were born, a skill that you didn’t know your friend had or even learning that a celebrity has similar interest as you. This past summer I had a similar experience. I was at a library waiting for my friend who needed help with his writing and while waiting, I found a book titled Writing on the Wall, which is a collection of short stories written by Mumia Abu-Jamal while serving his life sentence, which he is still serving.

Mumia Abu-Jamal is a former activist, journalist and a founding member of the Philadelphia chapter of the Black Panther Party. He was convicted in 1980 for the murder of a police officer named Daniel Faulkner. This followed his extensive coverage of a shootout between the Philadelphia Police Department and MOVE, a political and religious organization in Philadelphia between 1972 and 1985. MOVE was led by a man named John Africa, who was a friend of Mumia’s and a consistent enemy of the the police department. According to local news coverage at the time, John Africa was a villain. Mumia writes in depth about his conviction and the unbelievable amount of violence that he experienced leading up to his trial in detail in the early chapters of the book. It was difficult for me to read due to the gruesome nature of his situation.

But, aside from my disgust toward the situation and our country’s criminal justice system, I was also filled with a sense of pride and admiration. It had not truly occurred to me what it meant to be Black and a journalist in America before reading that, and the level of risk that people subject themselves to in the pursuit of presenting the truth when the truth is so desperately needed in the process of moving forward as a people. The press is often referred to as the fourth branch of government because of the important role that it serves in informing the public and serving as a check on government action. Where has this role been more clearly fulfilled than in the work of Black journalists like Ethel Payne, Ida B. Wells, Roi Ottley, Gordon Parks and Mumia Abu-Jamal.

This is a time when the president can sign executive orders that allow police to invade people’s homes and tear apart families, orders that allow the government to invade our neighboring countries with only the president’s permission and orders that can remove the social safety nets that we fought for so long through the democratic process to get. At a time like this, it’s all the more important that the public stays informed and that journalists hold the government accountable with as much passion and dogged persistence as those Black journalists of the past did.

Sandro Tavares, has been with Teens in Print for two years and writes about society and politics. Sandro plans on majoring in molecular biology.