‘We Quit America’: Our exit from a country designed to kill Black people

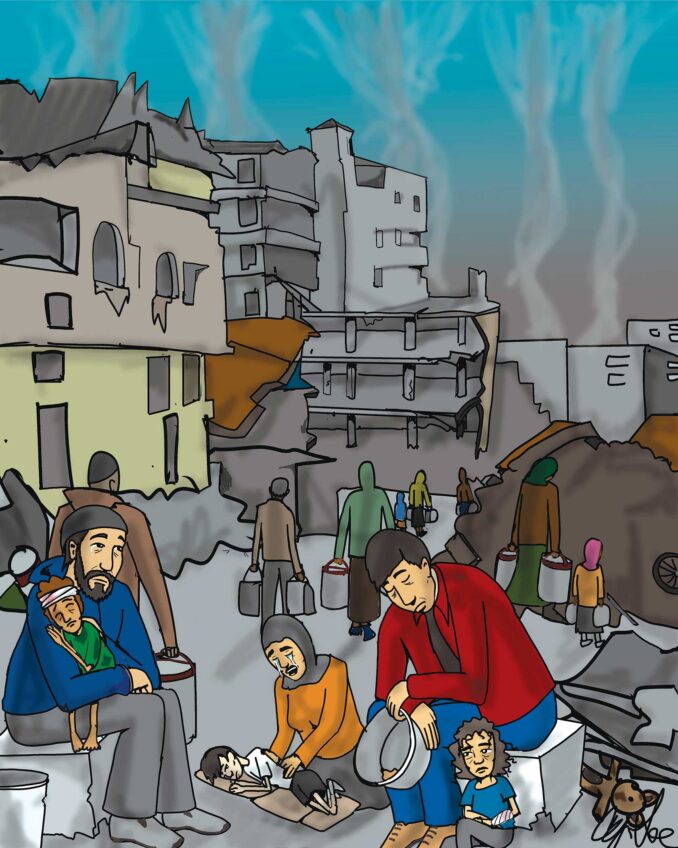

Quitting America was not one decision; it was many decisions over time. It was small moments of awareness, like a flashlight pointing to the exit in a smoke-filled burning house: I couldn’t see my own hands as they reached out to help me find the way, but I moved toward the exit anyway. I felt the heat closing in behind me. I couldn’t breathe. My nostrils burned. And slowly, my eyes, although stinging, adjusted to the painful truth: America is bad for Black people. And there is no making it better. I had to get out.

My first awareness that this country hated me was when Blake, a white high school classmate whom I believed to be a friend, flashed what I now know was racism. I can still see his sandy-brown hair, thin round spectacles, and smirking alabaster face as he dismissed my acceptance into Georgia Tech, my top choice for undergrad. “It is because she is Black and female that she got in,” he said as my classmates gathered in the back of physics class to congratulate me and to ask about my GPA and SAT scores.

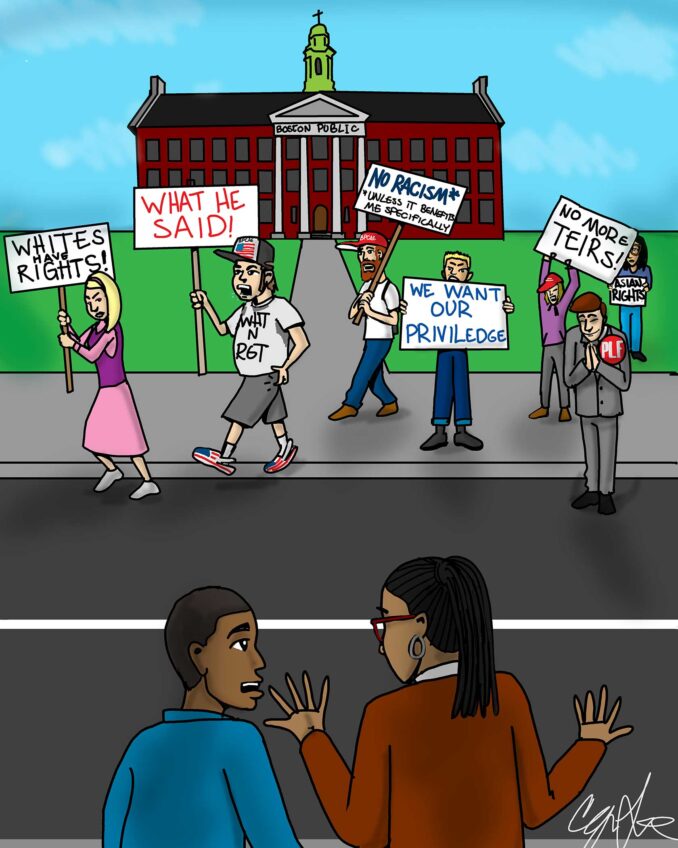

I felt such shame as I stood there, learning for the first time that something other than my high GPA (above a 4.0, weighted because of advanced classes) and strong SAT effort (an 1180, which meant I had outperformed 73% of test-takers) may have been at play in my acceptance. Affirmative action, a set of policies to improve educational and employment opportunities for minoritized groups that had been shut out of higher education and jobs because of histories of racism, may have rescued me, yes. Bias in college admission testing; underfunded schools in Black neighborhoods; and racist narratives that follow Black students around every day, telling them they are not smart enough, are all in the way of accepted forms of achievement — grades and test scores.

In 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against affirmative action in college admissions. This ruling denied the current and abiding role of structural racism in higher education access and the need to correct for its impacts and will make it less possible for Black people and certain other racialized peoples to go to college. I wasn’t even aware of affirmative action at the time Blake made the remark. Even if my race and gender had been part of the admission calculation, was there nothing about my high school performance he might have celebrated? In one fell swoop, he diminished my four-year effort to graduate at the top of my class.

As my classmates’ smiles dissipated, so did my excitement about my future.

America steals black wealth

My awareness continued during the two-year period in which every white household except one exited my previously all-white neighborhood after my family moved in when I was in college. In graduate school, I soon learned about studies that investigated the tipping point at which white people leave neighborhoods when Black people move in. One study found that the percentage of Black neighbors immediately preceding the tipping point is about 5–20%.

Can you blame white people? The policies and practices of redlining, a federal government program to rate neighborhood mortgage risk based on race, had synonymized low property values with the presence of Black people, thus fueling white flight. As a result of these dynamics, houses in Black neighborhoods historically have lower values than similar houses in white neighborhoods (Perry and Donoghoe, 2024). Thus, by the time the 2008 recession hit, my mother’s house went from stagnating equity to being underwater.

She lost her house in a short sale.

With the rise of white nationalism in the United States, I began daydreaming about returning to Jamaica, the land of my birth, and to a time when I was not Black. The tiny island would be a welcome reprieve from the unceasing racist ideology spewing from the political right since the election of President Barack Obama. My husband affirmed that a move to Jamaica was wholly possible and believed our nearly decade-long marriage, which was becoming strained, might have a better chance of surviving outside of the U.S. context.

Our family therapist, a Black man, had telegraphed to us that Washington, D.C., eats Black couples alive. The desire to make a name and career for oneself, along with the financial strain caused by living in one of the most expensive cities in America, was often too much for the Black couples he counseled, even those who loved each other and wanted to make it work. The couple who referred us to this therapist is no longer married. Both partners worked in relatively high-profile jobs and were driven in their careers. We also referred another couple to this therapist, and this husband and wife, too, are no longer together. She was a successful executive, and he was a federal government employee. They had two kids, one with special needs.

The stress of living in D.C. as a Black couple was made more challenging by long commutes, early-morning gym time, late-night dinners, and 12-hour workdays. We were exhausted. We became like college roommates who slept in the same place but missed each other, always on the way to or from class. Ronnie left for the gym each morning at 5 a.m. with a small suitcase filled with work clothes (often missing a pair of socks or his belt) while I was waking up with my computer to start the day. He cooked dinner after he got home, as I sat at the kitchen bar paying bills or making household to-do lists. We traded text messages and phone calls during the day, but it wasn’t enough to keep a marriage healthy.

And there is no making it better

At the same time, we were growing weary about whether our social justice work could produce the results we had hoped for. Ronnie had been working for the Democracy Collaborative on new economic configurations that could replace racial capitalism. As a public health-trained scholar, I was leading a private health foundation and working to move its grantmaking and other programs from a focus on health equity to one on racial justice. But I was burning out — and fast — and racialized aggression from my white peers compounded my stress. A board-suggested mini sabbatical was like a rescue tube for this drowning CEO.

Even during these periods of weariness, Ronnie and I found a certain kind of validation in Black comedy. I can’t tell you how many times we have watched Katt Williams’s “American Zoo” skit. It is so apropos for all our activism and is remarkably telling of Black people’s efforts in this country. We had been “tryin’ shit and tryin’ shit” as an activist couple in a long line of Black people in America who had done the same. Take stock of the arguments we as Black people have crafted to beat back racism, some of them in direct conflict with each other even when by the same person.

The famous debate between W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington is instructive. Du Bois was of the mind that a liberally educated Black elite should guide the way to progress, and that education, political power, and integrationist strategies would be our way into society. Washington argued that African Americans needed a more industrial-based education that shaped practical skills and trades. He believed that would allow Black people to work our way up from the bottom of America’s socioeconomic hierarchy.

Even now, Black public intellectuals and organizers present cogent arguments for our path forward. Some cry “Defund the police!” and others say, “We need pleasure in our movements.” The point here is that Black people try shit! We have prayed for relief, and we have strategized. We have been conductors on the Underground Railroad, and we have conducted ourselves according to white society’s expectations. We have protested, and we have led uprisings. We have burned down plantations and police stations, both of which have been hubs of state-sponsored violence with “officers” intent on controlling Black bodies. We have accommodated. Boy, have we accommodated! Working in and for white people’s companies. Working hard to stay between the lines to hold onto that salary needed to pay the bills.

We have gone to the most elite schools, and yet our quality-of-life outcomes are different from those of other racial groups. For example, within 40 years or so of matriculating, Black men who had graduated from Yale’s class of 1970 accounted for 10% of deaths among class members even though they only made up 3% of the class (Howell, 2011). What this demonstrates is that elite education doesn’t protect us from the darts of structural and interpersonal racism. In fact, the striving it takes to “make it” — to contend with and negotiate our way in America — is killing us faster and more efficiently than other racial and ethnic groups, save perhaps Native Americans on some measures.

We have also built our own businesses and communities in a self-determined attempt to insulate ourselves from racism — and each time, white mobs, threatened by any semblance of Black progress, burned them to the ground. We have fought in wars and come home to discrimination. We have voted and turned out the vote. It has been said on occasion that we (Black women in particular) have saved democracy. And still — look at where we are.

This is also why we quit. We have worked hard on this American project, yet America at every turn digs in its heels and resists the kind of transformative change required for Black people to realize our freedom. Each time it seems as if change is coming, such as with the election of a Black president, America wags its index finger like the late basketball player Dikembe Mutombo and says, “No, no, no. Not today.”

Perhaps not ever.

This article is excerpted and adapted from the book “We Quit America: Our Exit from a Country Designed to Kill Black People.” “We Quit America” can be purchased from www.wequitamerica.com. This post appeared first on New York Amsterdam News.