“Jennifer Packer: Tenderheaded,” at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University through July 8, pairs intimate portraits of the artist’s friends and family with still lives of funerary bouquets. Both subjects require emotional vulnerability and endurance to render and to experience. Though the show’s title refers to a tender scalp, the exhibition explores internal pain.

Jennifer Packer’s portraits are on display at the Rose Art Museum. Photo: Celina Colby

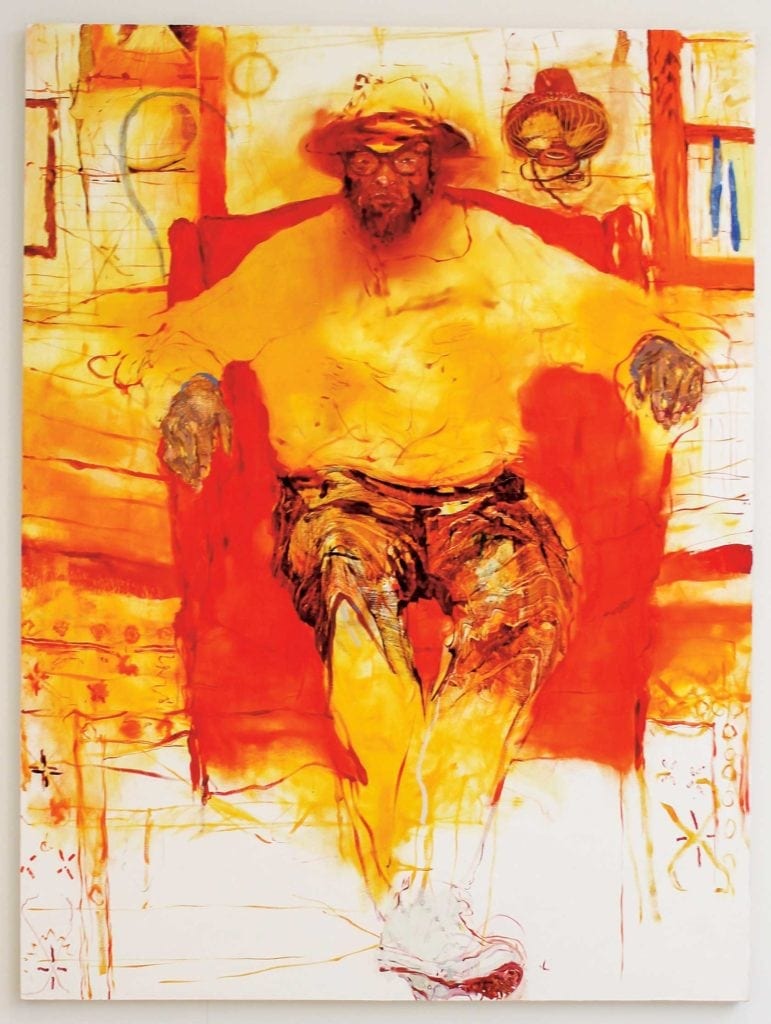

Packer’s visual style is consistent — abstractly representational, utilizing color and pattern heavily, often incorporating negative space at the base of the images. It’s her technique for applying paint to canvas that varies. “An Exercise in Tenderness,” a tiny portrait of a figure in a cobalt uniform, features at once heavy cakes of paint layered with broad brush strokes and thin, nearly translucent stretches of the same color revealing the texture of the canvas.

These varying techniques, often in the same image, create dynamic paintings taut with energy. “An Exercise in Tenderness” also provides a view of a police officer not as a villain, but as a person. He’s certainly not glorified, but Packer acknowledges his humanity, a tender move indeed in the age of police brutality.

The organization of the exhibit also alludes to the contemporary social climate. The mostly large-scale portraits, all of black subjects, are interspersed with smaller stills of funerary bouquets. These are a subtle reminder that the black community is under constant threat. At any time, these funerary bouquets might sit at the end of a casket, and the portraits will become a testament to what was rather than what is.

The bouquets are depicted with less abstraction than the figures. It’s a visual example of the absolute certainty of death. Life is less guaranteed.

Compelling images

Many of the figures engage directly with the viewer, looking out of their canvas thrones. They are confrontational, but not threatening.

In “For James III,” the subject’s wide, eerie eyes send chills down the viewer’s spine. This figure, unlike the others, is positioned upside down, suspended above the viewer. He appears to be lying on a mattress with his legs tucked underneath him in what might be a sleeping position — if it weren’t for those eyes. His painted chest has been marked up and engraved, a rough contrast to the smooth scallop pattern of the mattress underneath.

This figure is Packer’s father. The painting looks at him as adult children look at their parents, with greater understanding, greater disillusionment and perhaps greater sadness. Through those wide, staring eyes, perhaps Packer is seeing him for the first time.

There is much to be experienced in “Tenderheaded.” Packer’s work is like all our emotions, complicated and beautiful.