Rare 19th-century portrait of formerly enslaved man on view at Concord Museum

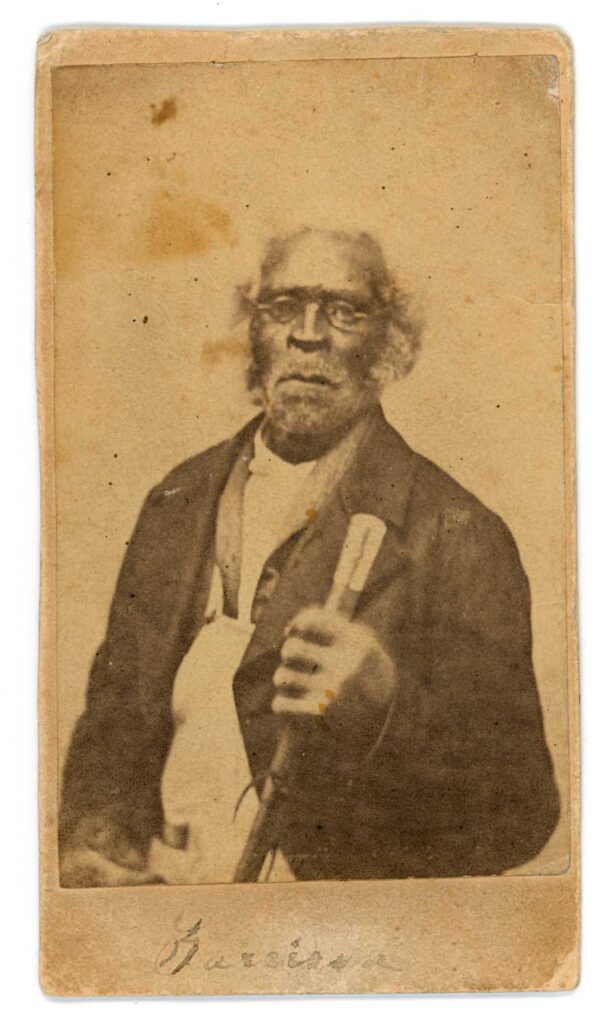

Tiny, black dots speckle the surface of the sepia-toned portrait. The man in the picture sports a collared jacket over a work apron, his countenance framed by thin-rimmed spectacles, a beard, and tufts of hair that just about blend into the background. In his hand, he holds a walking stick so prominently displayed that it almost becomes the focus.

This rare photographic image of a formerly enslaved man named Jack Garrison was taken between 1855 and 1860, a period when portraits of African Americans were uncommon. The carte de visite is the focal point of “Portrait Mode,” an exhibit at the Concord Museum that asks viewers to consider whose memory gets to be preserved.

“We’re really taking up this question of whose faces become part of history,” said Reed Gochberg, associate curator and director of exhibitions at the Concord Museum. “And I think really considering the power of portraits to make an individual life visible.”

The exhibit, on view until Feb. 23, 2025, includes a variety of other portraits of different scales and sizes. Garrison’s carte de visite measures 4.25 by 2.5 inches. But the collection also includes even smaller images that may have been kept in lockets and larger ones in the form of oil paintings.

The diversity of photo types showcases the history of picture-making in the 19th century and the evolution of technologies for creating portraits, Gochberg said.

Silhouettes of Emerson Cogswell and his wife, Mary Hunt. Concord Museum Collection, Gift of Cummings E. Davis.

Hollow-cut silhouettes, in which the profile of a subject was cut and mounted on a black background, became a favored, inexpensive form of portraiture. Decades later, daguerreotypes and ambrotypes gained popularity. Because these forms of photography were fragile and light-sensitive, they often became keepsakes housed in containers or cases, highlighting their use for circulation among family and friends.

All of the photos in “Portrait Mode” are connected to Concord somehow, but they all symbolize different lives, experiences and moments.

The Concord Museum’s collection includes three copies of the portrait of Garrison, who was born into slavery and moved to Concord in the early 19th century where he lived as a free man, got married and had children. The one on display in “Portrait Mode” was donated in 1913 by a woman named Olive Brooks Banks.

Before donating the image, Brooks Banks inscribed it with Garrison’s story. Although questions remain, the tale goes that when relatives from the South visited Concord in the 1850s, Garrison hid until they left. It was shortly after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, which required that enslaved people be returned to their owners even if they lived in a free state. By then Garrison had called Concord home for over four decades. His relatives’ visit seemed to threaten the sense of security he had built for himself and his family.

“It’s even more powerful to think of him sitting for this portrait at that moment in time,” Gochberg said, “and choosing to make himself visible, and choosing to meet the gaze of the camera.”

The portrait invites audiences to imagine what Garrison’s life might have been like at the time the picture was made. He was in his late 80s and would have had to travel to Boston to have the photo taken. How did he get there? What was the weather like that day? Had he been working before sitting for the portrait, as evidenced by the apron? Did the jacket belong to him or had he borrowed it for the portrait?

“Looking more closely raises these questions about the kinds of intentional choices that he was making in terms of how to represent himself,” Gochberg said.”

The fact that Garrison’s walking stick — a gift and the commemoration of which is speculated to have been the reason for the portrait — and carte de visite were collected speaks to his status as a respected part of this community.

Some photos in “Portrait Mode” were passed down through family members, such as a portrait of William Johnson Damon, a 21-year-old man who was killed in the Civil War. The portrait, created posthumously decades later likely from a daguerreotype, was donated to the museum last year. Objects such as this emphasize the idea of memory and loss, Gochberg said.

While some subjects had their names etched in history, some portraits remain unidentified. Yet Gochberg chose to include them in the collection.

“We may not know the name of the person whose face we’re looking at from say, 1840, but at one point in time somebody did.”

Including them in the exhibit presents an opportunity to restore their place in history.

“Portrait Mode” is in conversation with other similar exhibits at the Concord Museum and aligns with the organization’s broader initiative to expand the stories it tells about American history and the figures who are considered a part of Concord’s history, Gochberg said. The special exhibit currently on view, “What Makes History? New Stories from the Collection,” opened in the spring and asks similar questions about what objects are collected and how museums choose to tell stories.

“Portrait Mode,” she added, was also informed by other historical projects at institutions in Massachusetts and nationally, such as “Framing Freedom,” an exhibit at the Boston Athenaeum that showcased the albums of Harriet Hayden and other African American abolitionist figures in the 19th century, and last year’s “Unnamed Figures” at the American Folk Art Museum.

Exhibits such as these encouraged Gochberg and her colleagues to look at familiar objects from the Concord Museum’s collection in new ways and consider the different stories that can emerge from a single object as in “Portrait Mode.”

“By putting these portraits of well-known subjects in conversation with portraits of lesser-known figures like Jack Garrison, or even of figures who are now identified or whose names were never recorded, I think that it, in many ways, is showing how all of these people are part of history,” Gochberg said. “It is expanding the story of who gets to have their life recorded. So even if we don’t know the name of the subject, we can meet their gaze looking at a small portrait of them that was preserved in a locket or in an album.”