The delicate balance between community wealth building and affordable housing

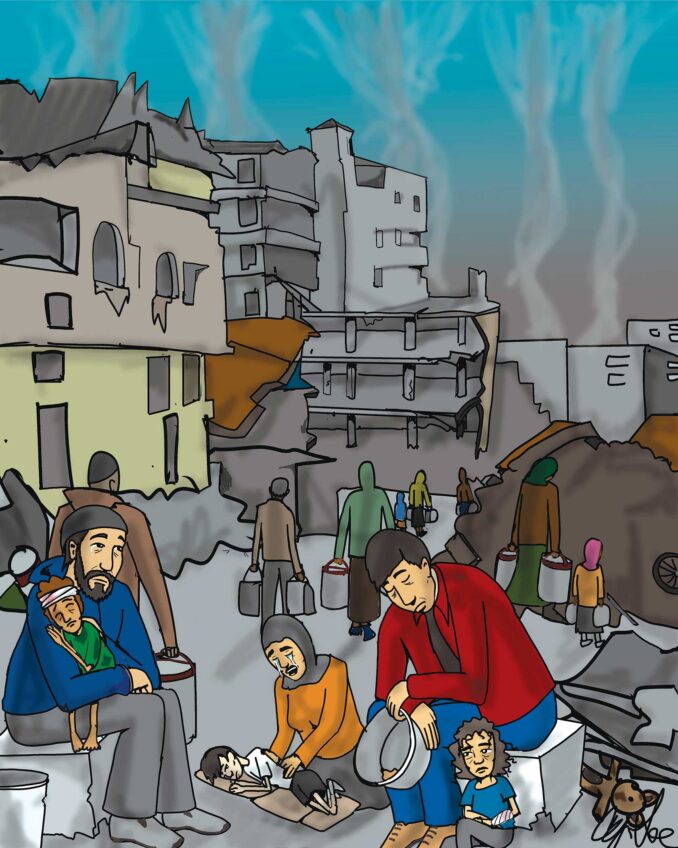

As major cities around the country struggle with providing affordable housing to their long-standing residents, Boston reigns supreme as a poster child for gentrification. Over the past 30-plus years, Boston community leaders and government officials have tried to stem the tide of displacement caused by gentrification. Mayors and city councilors in successive administrations have worked closely with housing advocates and developers to face the challenge of creating affordable housing to protect neighborhood stability and enable future generations to live in the communities where they grew up.

In Boston, we have some of the highest real estate prices in the country. In many cases, local residents were and still are being priced out of their own communities as a result of the high costs of renting or homeownership.

Starting in 2000, the city of Boston, with the assistance of a handful of community development corporations, paved a way for affordable housing to be created by subsidizing the construction of the housing, then requiring the affordable homes to be sold to local families through lotteries at low or no money down and at a reduced price. This provided new housing for thousands of families in Boston at a price they could afford, within their own communities.

The way the system basically worked was that the city provided subsidies to nonprofit developers who would then sell new homes to income-qualified lottery winners at approximately 50% of the fair market value of the home or townhouse at the time. In addition to the discounted price, there was often a low or no down payment needed to purchase the home as part of these programs. But the flip side of that offer was, when it came time to sell that home, they would have to sell it at an affordable price so the next Boston family could still receive a benefit from the original subsidy. That way, another Boston family could have an affordable house they could live in more than 30 years after the original affordable house was created.

The way this long-term affordability was guaranteed was through deed restrictions, which were binding covenants signed by homebuyers and placed on the deeds of the homes when they were purchased. The restrictions set guidelines for annual appreciation — no more than 3% to 5% a year — thus limiting eventual sales prices to a figure well below market rate, in order to maintain the units’ affordability.

This was a way for the City of Boston and grassroots community organizations to create a large amount of affordable housing stock — as many as 3,000 units over the last few decades

Now, fast-forward 20-plus years later: Housing prices in Boston have continued to skyrocket and many of the families that purchased these affordable houses have raised their families as they paid down their mortgages for two decades. Now they want to take out the equity from their homes to pay for typical family expenses, like school tuition for a child, home repair, or medical care for themselves or an aging loved one. But the deed restrictions on the properties limit the amount that they can take out in an equity line and also require city approval.

Based on records at the Registry of Deeds, only a handful of the 34 or so homes in one community development program, known as Back of the Hill, have received home equity loans. So it’s reasonable to assume that most requests for equity lines are not granted — and it’s worth finding out the reasons why.

Another issue of concern is the fact that these homeowners, who live on the back side of Mission Hill, can pass along their property to their heirs, but only those who are income-qualified can remain in those homes. Heirs who earn too much must sell the properties. This is a policy no longer in effect for newer properties. Perhaps there’s a way of revisiting the old covenants to conform to the newer policy.

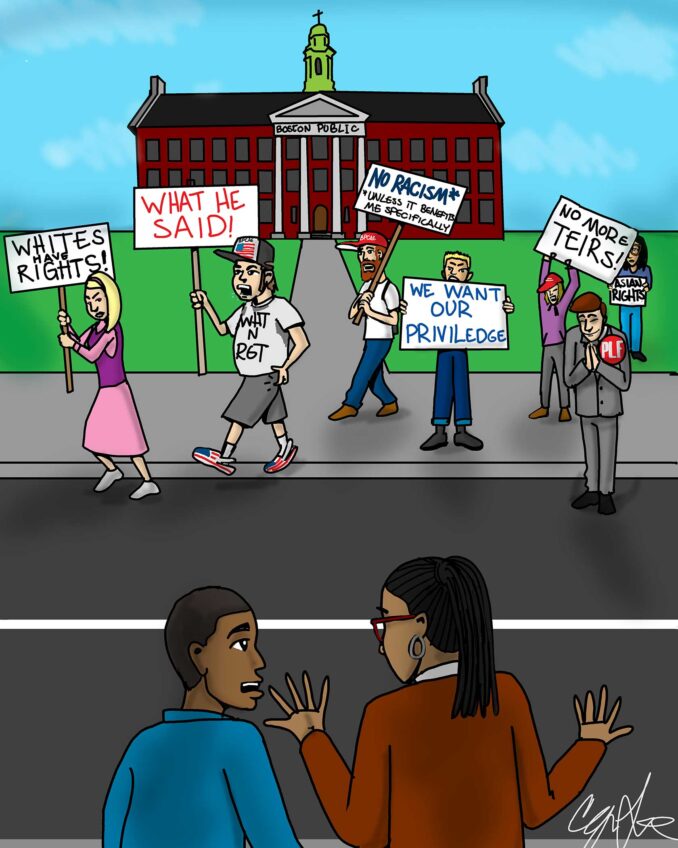

Last week these issues came to a head in a Boston City Council hearing called by Tania Fernandes Anderson, the District 7 Boston city councilor who represents Roxbury. During the hearing, members of all sides presented their views on these challenging questions. How long is too long to require a family that received a subsidy to not have clear access to the full equity in the home they own? And how do you still provide affordable housing for the next generation of Boston residents?

The Banner urges the city take three steps: One, that the city work more closely with homeowners to increase access to equity in their homes; two, that deed restrictions forcing over-income heirs to sell the properties they inherit be dropped, allowing them to live in the houses if they so choose; and three, that the city allow homeowners to sell their properties for fair market value (in most cases, over $1 million for each property), but with one condition — that the homeowners pay the value of the original housing subsidy, adjusted for inflation, into a public fund to be used to build new affordable housing.

These new funds could go a long way to help subsidize the cost of new housing for the next generation of Boston families who want to stay and own a home in their own communities.

To realize a better Boston, we must all take responsibility for our own community and give back to it as much, if not more, than it gave to us. To just say “I want mine” and turn your back on the very system that helped you buy a home will not keep low- and middle-income Boston families in our neighborhoods. On the other hand, if the city administration holds fast to rules that were created 20-plus years ago with good intentions but over time have become outdated, then city government is also not serving the broadest needs of our community.

It is time that all parties sit down, leave their egos at the door and put the true needs of our community residents first. There is enough prosperity in Boston’s real estate market to go around, as long as all concerned parties don’t think their view is the only view and their answers are the only right answers.