New book explores the evolution of Black homeownership on Martha’s Vineyard

Richard Lewis Taylor is a longtime summer resident of Martha’s Vineyard. In 1979, he and his family purchased a cottage in Oak Bluffs, one of the island’s six towns, after several Roxbury families introduced the island to him, he said.

When his family bought the property and began spending summers riding bikes and going to the beach there, they joined a long legacy of Black families who own property on Martha’s Vineyard.

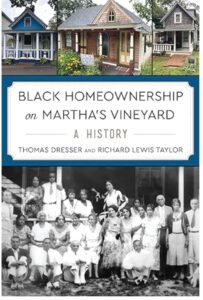

While many people know about the presence of Black people on the island, the history of that heritage is lesser known. Taylor and his friend Thomas Dresser, also an Oak Bluffs resident, set out to change that. In June, the pair published “Black Homeownership on Martha’s Vineyard: A History,” a book tracing how the island’s Black population has evolved from its nascence in the 19th century to its status as a burgeoning community for Black homeowners.

“The African American presence is not an accident here,” Taylor said. “It’s a continuum over generations.”

Taylor himself is deeply embedded in Vineyard life. He is president emeritus of Union Chapel, a non-denominational church on the island, and he leads the Union Chapel Education and Cultural Institute. He also writes a weekly column on Oak Bluffs for the Vineyard Gazette.

Taylor’s most recent book isn’t the first time he has delved into the island’s history. In 2016, Taylor published “Martha’s Vineyard: Race, Property, and the Power of Place,” detailing the coexistence of Black and white populations on the island and the birth of an African American community. The book draws on Taylor’s interests and expertise as a real estate executive.

Following the publication of that work, Taylor said, he received questions about the Black population of Martha’s Vineyard, particularly whether it was shrinking.

In their recent work, Taylor and co-author Dresser, who previously wrote about early African Americans on the vineyard, sought to answer those questions, turning their eyes toward generations of Black family trees and the homes passed down within them.

“I felt it also was important to catalog the early years of homeownership and what gave rise to different pockets of homeowners on the vineyard,” Taylor said.

While Taylor knows firsthand the experiences of Black families on the island, having summered there for decades, the authors relied on accounts from and interviews with people with historical ties to tell the story. Among their selected vignettes are ones about the Shearer Cottage, now an institution, bought by a formerly enslaved African American named Charles Shearer and his wife Henrietta Shearer, and about Reverend William Jackson, a town crier who rented, then purchased, his cottage in the late 1800s. These tales, along with commentary from current vacationers, weave a narrative of Black homeownership that dates back centuries.

In the early days, Black people who bought property on Martha’s Vineyard were from the service class, Taylor said. They were maids, chauffeurs, cooks and owners of segregated small businesses

In the 20th century, Martha’s Vineyard provided a respite from the challenging reality of city life.

In the summers, Black politicians and celebrities frequented the Villa Rosa, established in the 1950s. Photo: From “Black Homeownership on Martha’s Vineyard: A History”

“For many Black families, Boston was sort of tough to navigate, socially, professionally and even politically,” Taylor said. “And the Vineyard, because of the demographic composition and the sense of historic presence of Black folks beginning in the 1800s, there was a sense of belonging, a sense of community in a place where you could relax and be yourself.”

The service class laid the foundation for Martha’s Vineyard as it is known today, but their work wasn’t without its challenges.

On the mainland, racially restrictive tools — ordinances, covenants and eminent domain — were used to stop Black people from buying property in significant ways. While it didn’t happen that way on the Vineyard, there was one important instance of it.

In their research, the authors discovered that approximately 30 Black families were removed from the Methodist Campground in the late 1800s and early 1900s, “probably the most significant discriminatory act here with regard to real estate that we’ve uncovered,” Taylor said.

But the families recovered.

Charles Shearer, a former enslaved African American man, and his wife Henrietta Shearer bought their property, now the Shearer Cottage, in the 1900s. Photo: From “Black Homeownership on Martha’s Vineyard: A History”

In the book, Taylor and Dresser juxtapose the ability to buy land freely on the island with the inability to buy land freely on the mainland of America. Methods like redlining and blockbusting used on the mainland by real estate brokers, lawyers, banks, insurance and the government to tell Black people where they could and couldn’t buy property were not used on the Vineyard, Taylor said.

At one time, property ownership on the Vineyard was centralized and focused on Oak Bluffs. Today, Black homeowners buy all over the island, putting down roots in Edgartown, Vineyard Haven and West Chop. One of the most well-known real estate brokers on the island is Jennifer B. DaSilva, an African American woman whose family began vacationing there in the 1950s.

Today, the island isn’t just a destination for Massachusetts residents or New Englanders. Vacationers, particularly African Americans, come from afar, hailing from Atlanta, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia and New York.

“We are part of this island, and we’re not guests,” Taylor said. “And more and more, people are thirsting for that, and they’re coming for that.”

Martha’s Vineyard has become a “national platform for African Americans,” he said. It’s home to renowned events such as the Martha’s Vineyard African American Film Festival and the Martha’s Vineyard Comedy Fest and a hub for academics like Henry Louis Gates Jr. and the late Charles Ogletree.

The island is also the location of a church that meets on summer Sundays with ministers from across the country as guests. Recently, about 500 people sat outside on lawn chairs and beach chairs for a church gathering, Taylor recalled. Also of note are the political figures with properties on the island, like the Obamas, and those who visit it, such as Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Ketanji Brown Jackson, who attended the film festival earlier this month.

In Taylor’s eyes, Martha’s Vineyard is a place for happiness and joy.

“If you’re looking for an environment for your children and your grandchildren who are of African descent, and you’re looking for a physical space with a broad range of institutions and organizations that will support them, that will pour into them, allow them to feel free and to be themselves, Martha’s Vineyard would have to be on the top of your list,” Taylor said.