Some Boston neighborhoods experience more severe effects from heat exposure than others. Communities are organizing to green their neighborhoods in the name of health and equity.

By Galiah Abbud, Chloe DaSilva, Peyton Doyle, and Sarah Liu

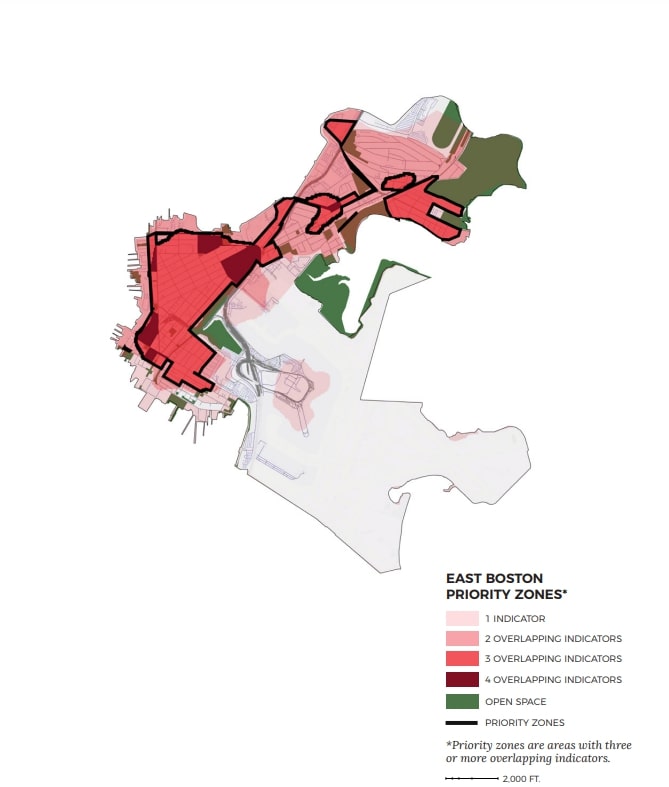

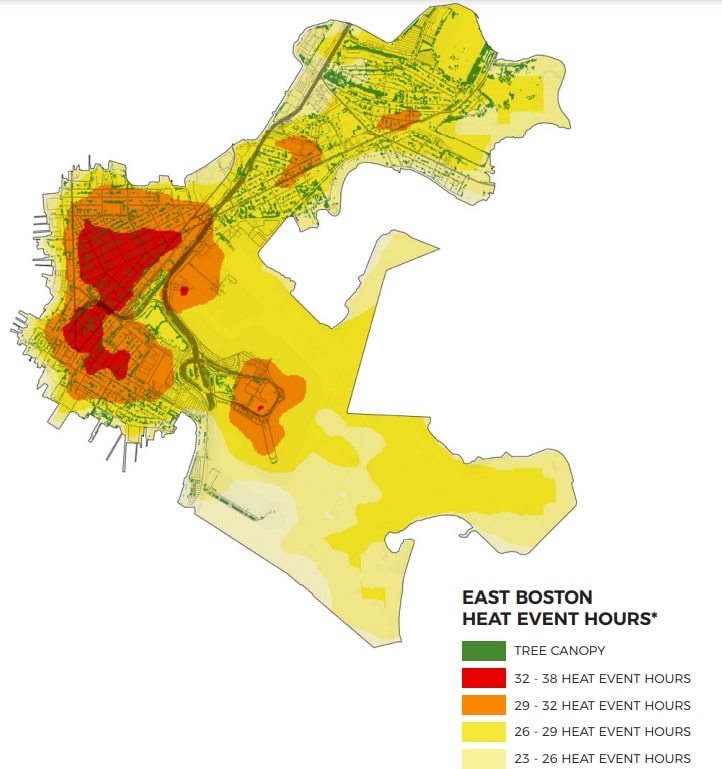

It’s the middle of July in East Boston, a heatwave hovers and there’s little natural shade to enjoy if you’re waiting for a bus in Maverick Square. The neighborhood has the least tree cover in the city and is hammered during heat events.

Meanwhile a few miles west, the street in front of the Roxbury Latin School in West Roxbury is much greener — and, as a result, students, and residents in the area can enjoy the reprieve of shade trees.

More than a quarter of Boston is covered by tree canopies, but the totals vary greatly from neighborhood to neighborhood. In many areas, residents live on “heat islands” impacting residents’ physical and mental well-being. Many of these islands have large minority populations.

Nancy Smith, a leader of the City of Boston Community Emergency Response Team (CERT), and a Roxbury resident, participated in a study conducted by the Muesum of Science called “Wicked Hot Boston.” During the course of the study, which compared temperatures in different locations around the city at the same time, Smith had a startling discovery about how heat impacted her daily life.

“OMG, we were on some site and the guys says ‘Oh, this is one of the hottest areas today in the city,’ and I said, ‘That’s my office!’,” Smith remembers. “My office was down on Mass Ave., across from Boston Medical Center, and there’s nothing but concrete down there.

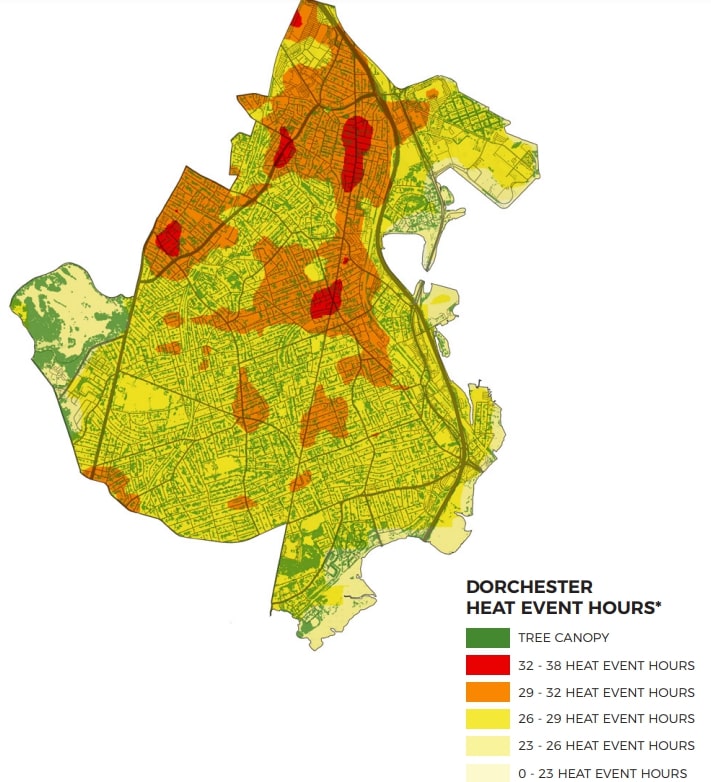

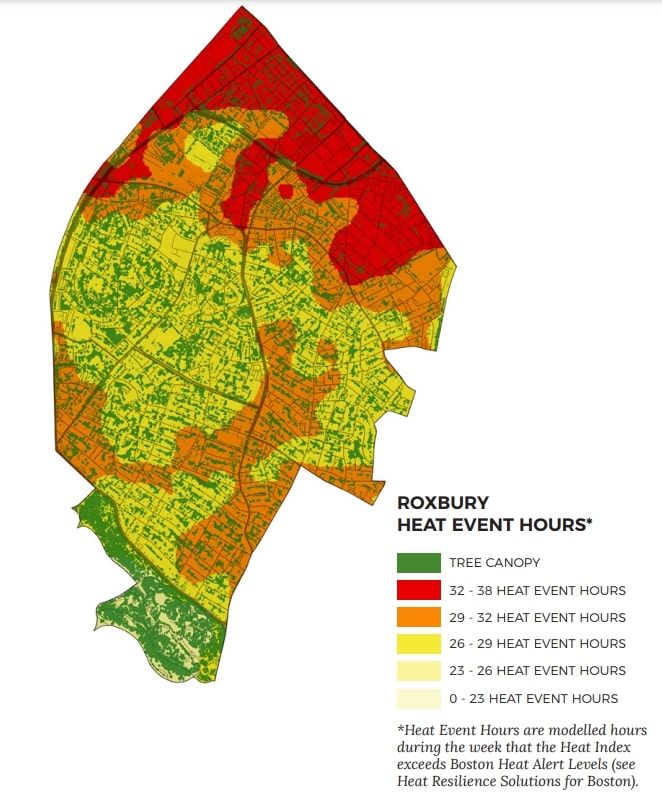

The disparity did not occur naturally — it’s the result of actions taken years ago. Maps of tree coverage, and often by extension heat maps of the city, reflect the redlining maps implemented by the government in the mid-20th century, which discriminated against minority groups in getting housing loans. Neighborhoods marked by these maps as being lower grade back then — like Dorchester, Roxbury, Brighton, Charlestown, and East Boston — are all below average when it comes to canopy cover today.

According to the Boston Heatmap Index, these areas are also often the hottest in the city and are most impacted by heat events. Dorchester, East Boston and Roxbury also have three of the highest minority populations in Boston according to the city’s census data. In East Boston, 66% of the population is non-white, in Dorchester 78%, and in Roxbury 89%.

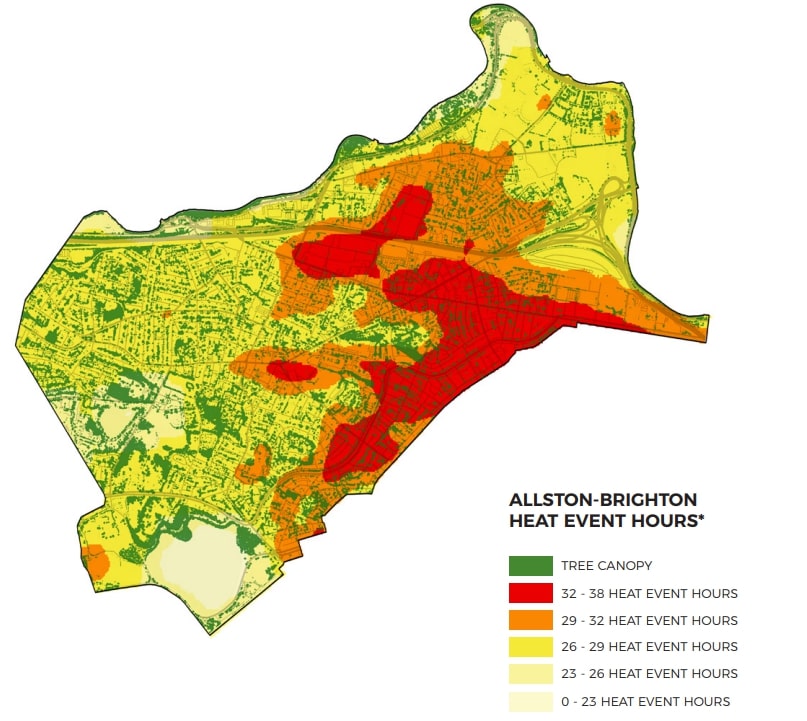

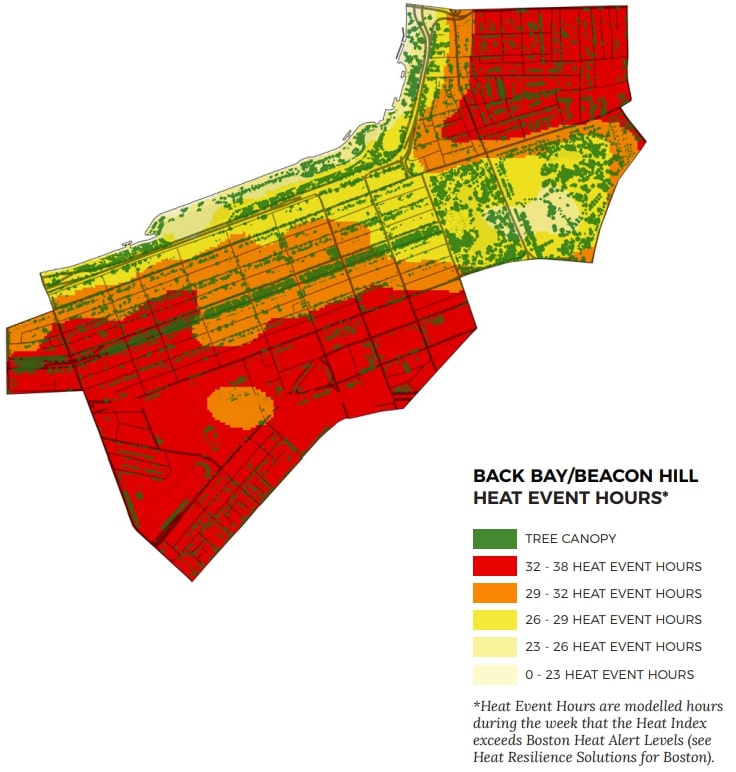

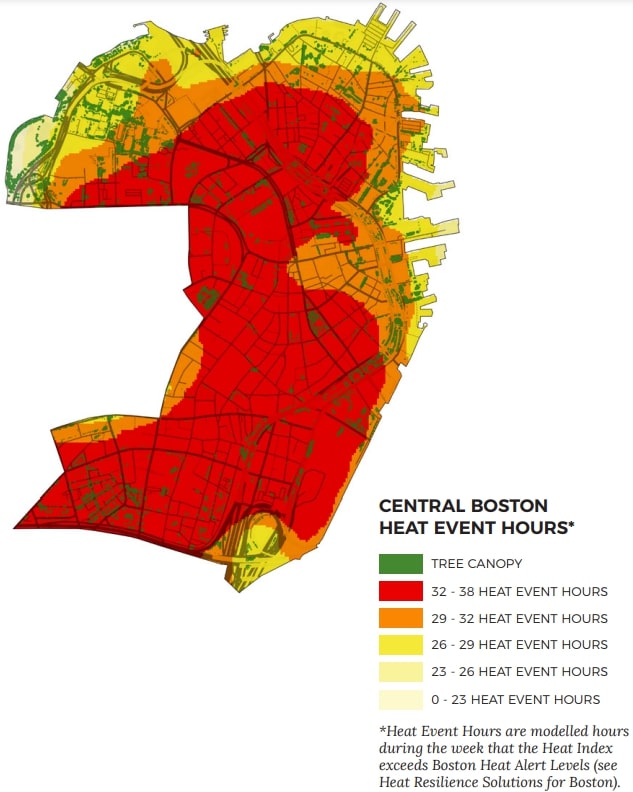

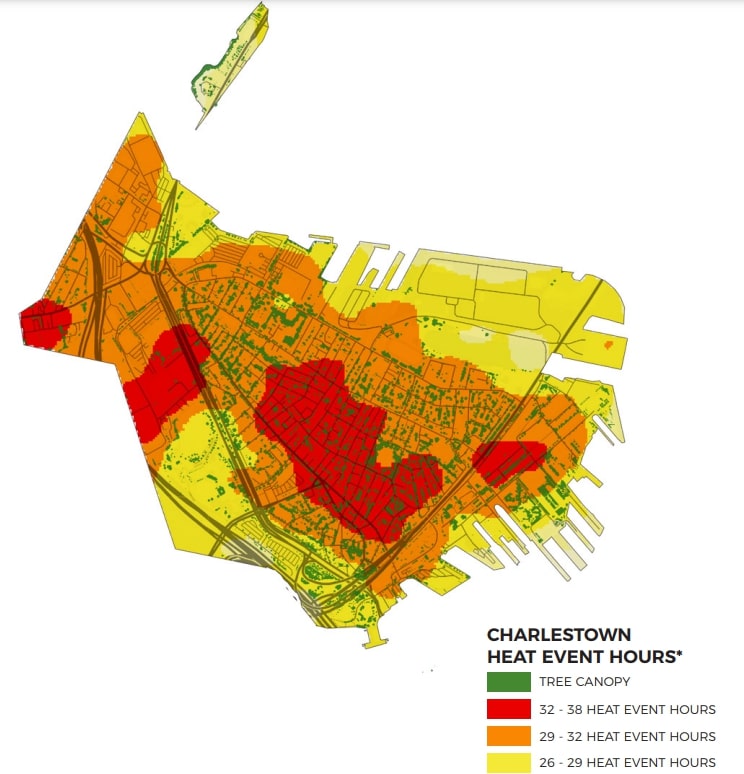

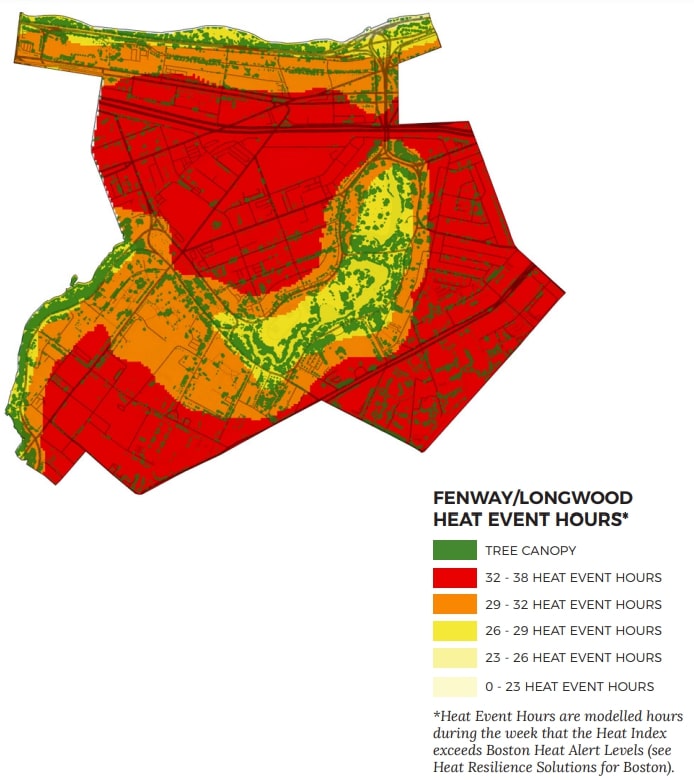

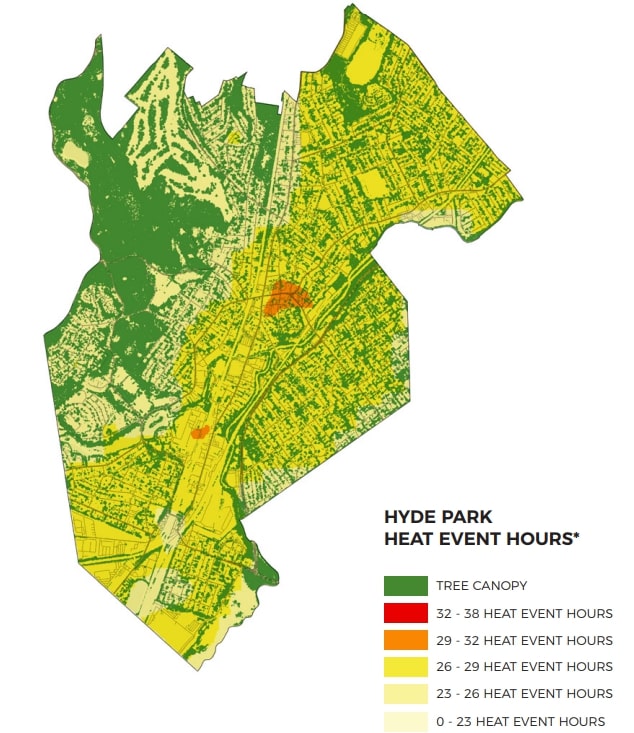

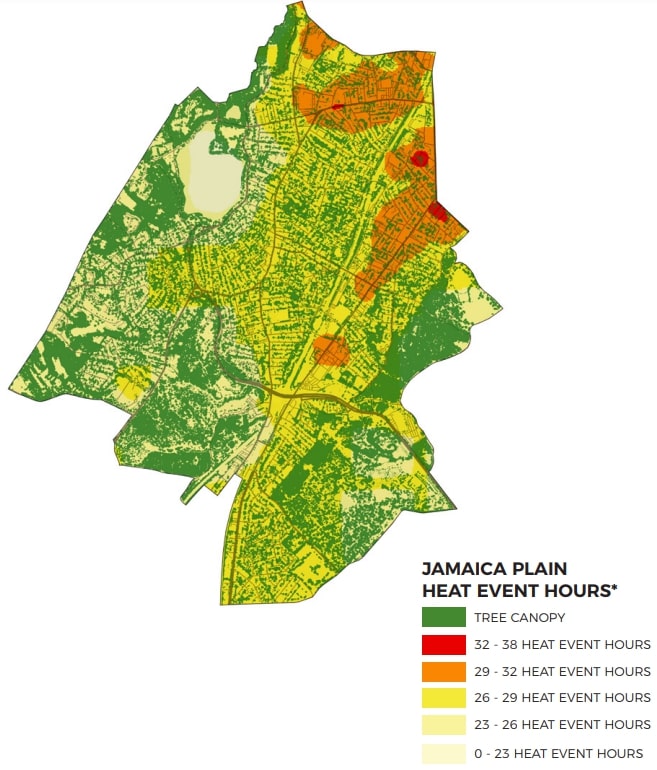

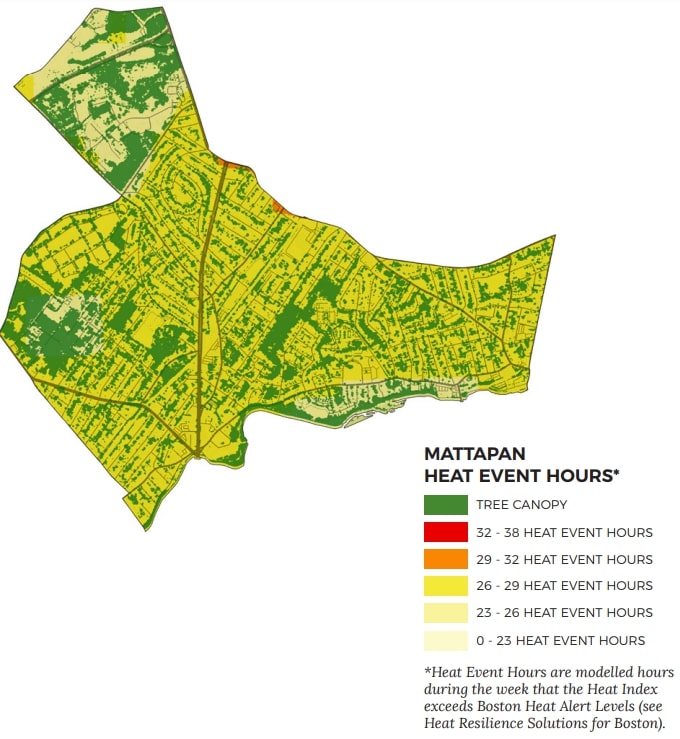

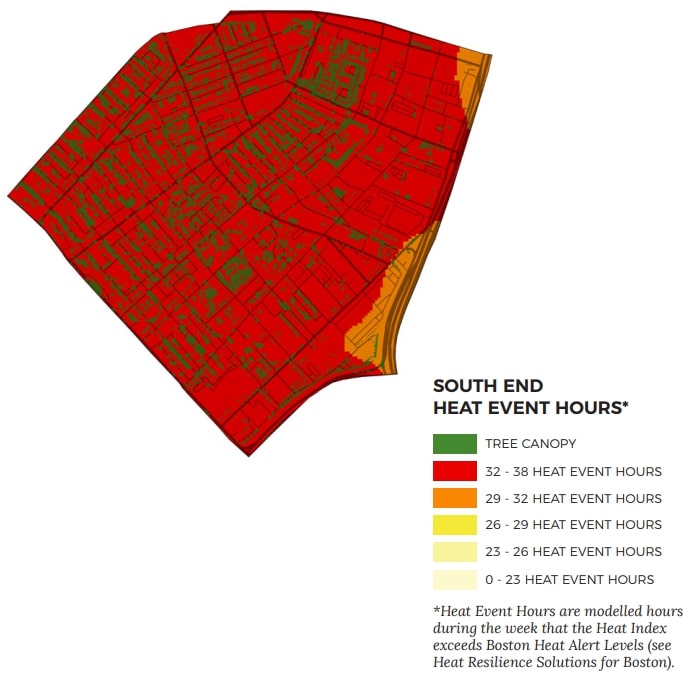

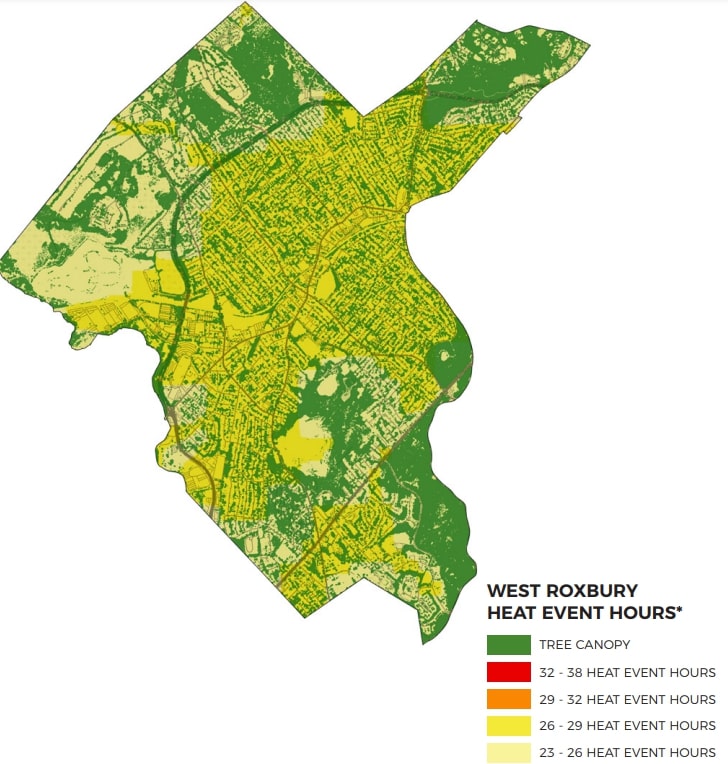

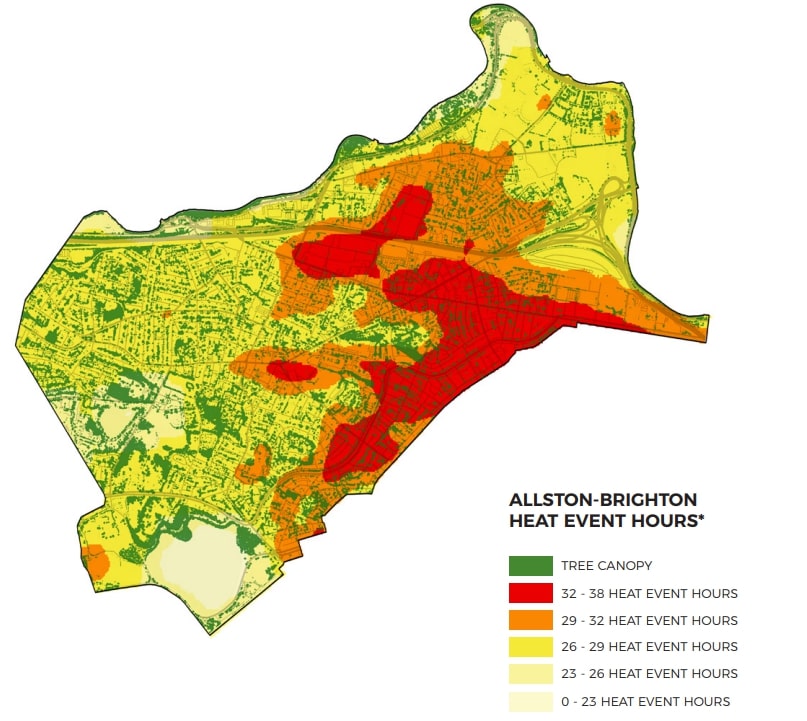

The hot spots in Boston’s neighborhoods

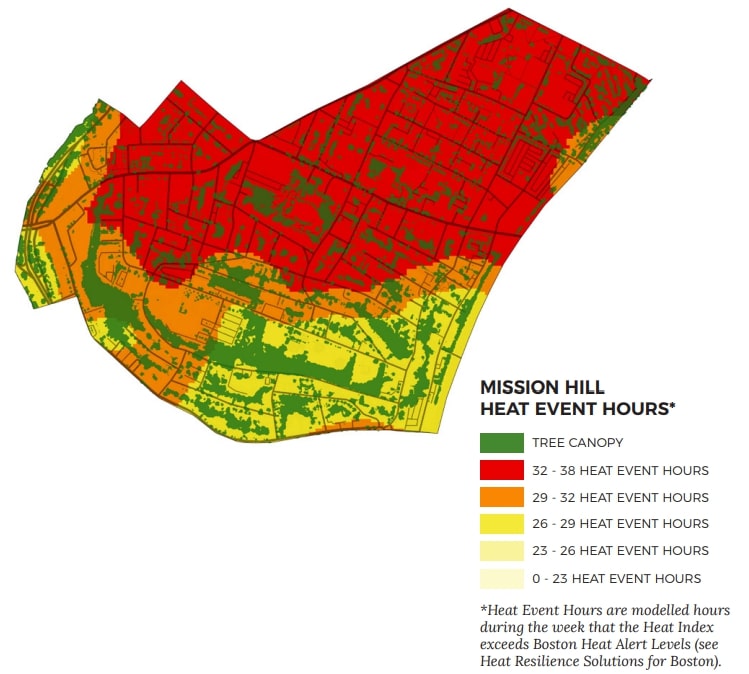

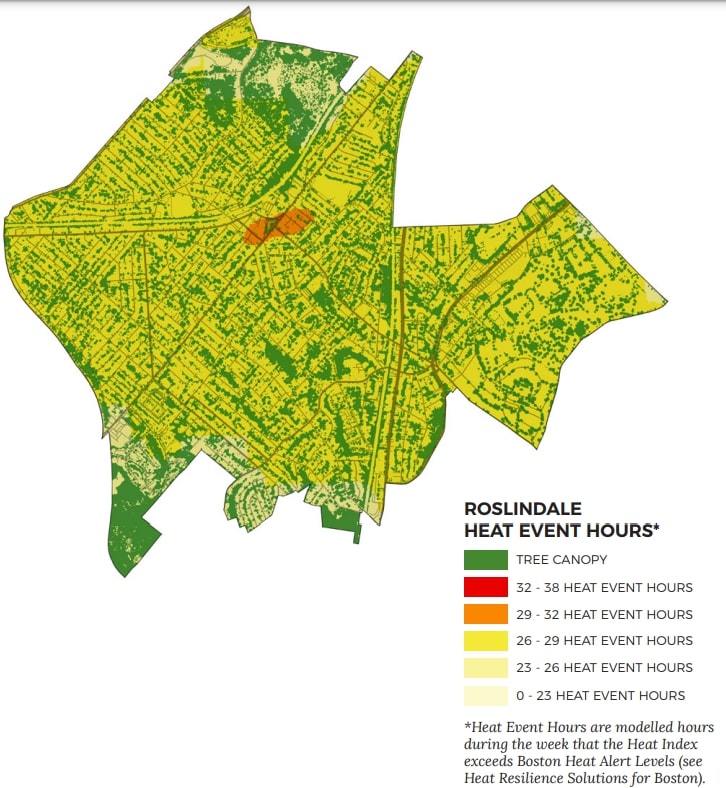

The number of hours within a week where temperatures exceeded 95°F during the day and 75°F at night. Source: 2022 Heat Resilience Plan

Allston/Brighton

Back Bay/Beacon Hill

Central

Charlestown

Dorchester

East Boston

Fenway

Hyde Park

Jamaica Plain

Mattapan

Mission Hill

Roslindale

Roxbury

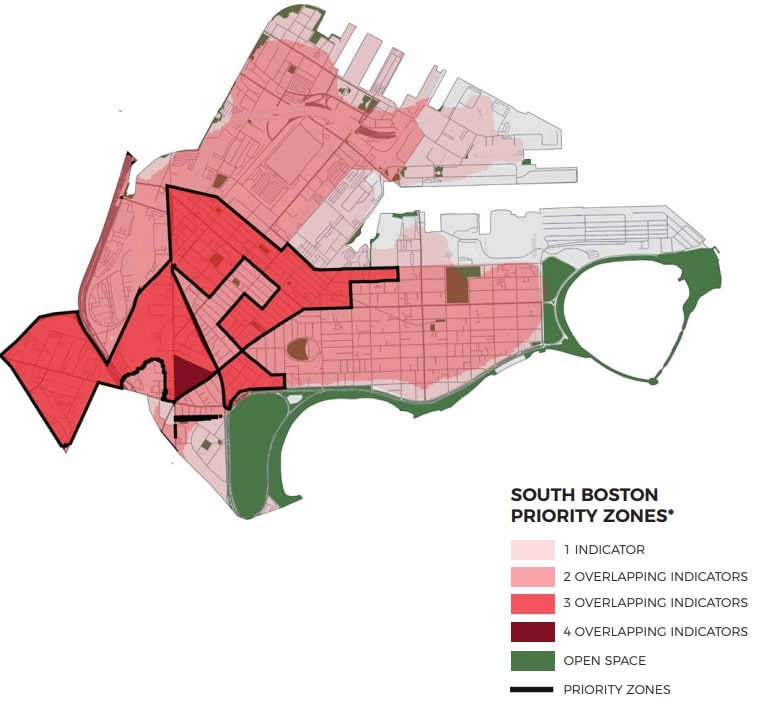

South Boston

South End

West Roxbury

Allston/Brighton

This is not just a Boston problem, after examining nearly 50 U.S. cities in 2021, the EPA found that “Black and African American individuals are 40% more likely than non-Black and non-African American individuals to live in areas with the highest projected increases in extreme temperature related mortality with 2°C of global warming.”

To be sure, tree cover is not the only factor in making neighborhoods hotter. Oftentimes roads, sidewalks and buildings absorb sunlight and reflect it back as heat. As a result, areas that are more densely populated experience greater heat.

In addition, a recent study cites heat emissions from things like cars and buses, industrial facilities, and building heating and cooling systems, as a major factor for temperature rises in urban areas.

Tree coverage and shade varies across Boston neighbhorhoods

Whether it’s caused by lack of tree cover or other factors, that heat leads to a number of health risks for people of all ages.

Nancy Smith recalled an impactful moment that underscored the significance of trees in hotter urban areas. Reflecting on her time working near Mass Ave., opposite the bustling Boston Medical Center, she remembers the stark concrete landscape. Amidst this heat, she witnessed individuals experiencing homelessness seeking refuge under the sparse trees dotting the area.

“This is probably one of the worst things that I saw in my career, when they fenced off the trees so that people wouldn't have access to sit under the trees,” Smith said. “That's inhumane by all accounts, even though people may have been doing other bad things under trees, but you now have removed any form of way for them to stay cool. They fenced them off.”

Dr. Patrick Kinney is a professor of environmental health at Boston University. He has spent extensive time studying the ways heat impacts health and the effect on particular groups of people. Kinney said that elderly individuals are at the greatest risk of death during heat events.

Trees however can help combat the risk of death during heat events.

“We know from epidemiology studies that places that have more trees have lower, in general, mortality rates,” Kinney said.

Older residents often feel the effects first, but they’re not the only one’s at risk during heat events. Kinney said that children and middle-aged adults can also be harmed.

“Construction workers or agricultural workers are quite vulnerable to heat stroke and death during heat waves,” Kinney said. “For children, they can get really dehydrated if they're running around and not drinking enough liquid. So we see effects on a range of different kinds of kidney issues, for them.”

The lack of trees that contributes to the heat, also can impact the mental health of residents.

According to Peter James, an associate professor at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, trees can lead to decreased levels of stress, and depression, as well as better cognition.

“We have seen both experimental studies and observational studies that show that exposure to trees could improve cognitive function, alter our brain activity, decrease blood pressure, and improve our sleep,” James said in an interview with WBUR in 2021. “These changes translate into long term changes in incidents of depression, anxiety, cognitive decline and even chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease and cancer.”

Recognizing the way heat impacts neighborhoods unequally across the city, many residents are organizing to combat the issue on their own. Groups like Southie Trees and Speak for the Trees have developed over the past two decades, attempting to improve Boston’s canopy.

Donna Brown, the executive director of the South Boston Neighborhood Development Corporation, said Southie Trees is an important branch of their group.

Much of the planting work done by the group is on South Boston NDC properties. Brown also said the group makes sure to make room for trees on their new developments.

Brown also said the group has found other ways to contribute to the neighborhood’s canopy when they don’t have new trees to put in the ground.

“The Southie Trees program does more tree caretaking in the summer,” Brown said. “We have high school students who work with our staff to plant flowers around the street trees and to water the street trees and to build awareness and encourage people to water street trees near their homes and businesses.”

David Meshoulam is the Executive Director and Co-Founder of Speak for the Trees which is constantly working to help local communities whether it's through free giveaways, employment opportunities, climate education, or tree walks.

Nothing is done by Meshoulam’s group without the city’s residents in mind

“At the end of the day, the trees belong to the community,” Meshoulam told the Conservation Law Foundation. “We’re committed to making sure that some of the harm that was done through things like air pollution is mitigated by increasing the canopy and improving the health for the residents who live there.”

The concerns and efforts of residents and the scientific community haven’t gone unnoticed at City Hall. Mayor Michelle Wu’s administration has brought a new emphasis on environmental justice to the city.

An early hire by the new mayor was Todd Mistor, who leads Boston’s Urban Forestry Department.

“[The Wu Administration] has been incredibly supportive of the urban forestry division,” Mistor said. “We’ve invested a lot of money in our division to expand the capacity — hiring myself as a director, hiring more arborists, hiring more field staff, including graduates of the PowerCorps program, which is a green industry training course to get more people, especially from economic justice neighborhoods into the green industry.”

Mistor said that with the 2023 budget his department aims to plant 2,000 trees each year. His team is working to find ways to get new trees whether it's through corporate grants or other projects for the city.

In announcing an $11.4 million grant from the U.S. Forest Service to support the city's plan, Wu said “These investments will facilitate the sustainable growth of Boston’s trees, wherever they live. We’ll have more beautiful, shady, accessible streets for all our residents and connect our community members to good-paying green jobs to advance our city’s climate goals.”

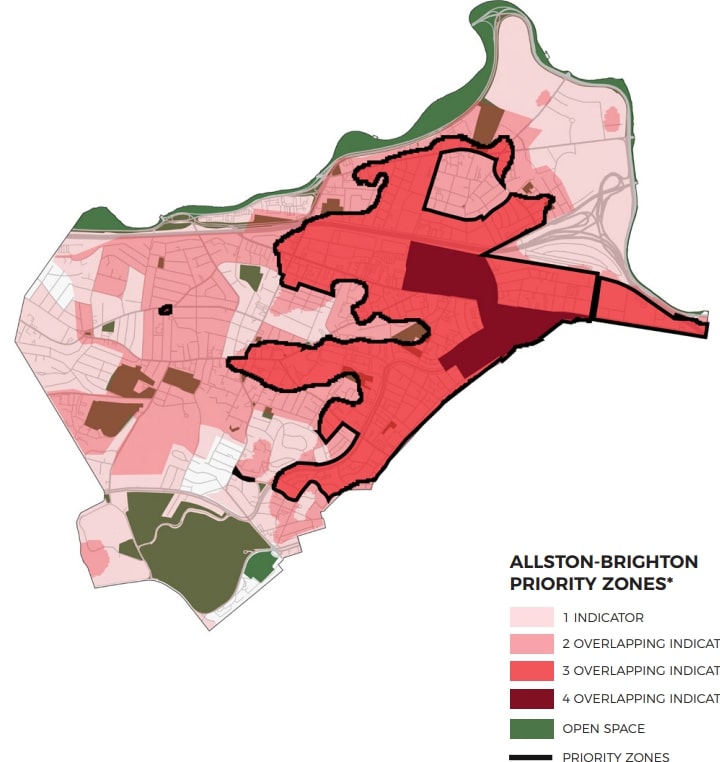

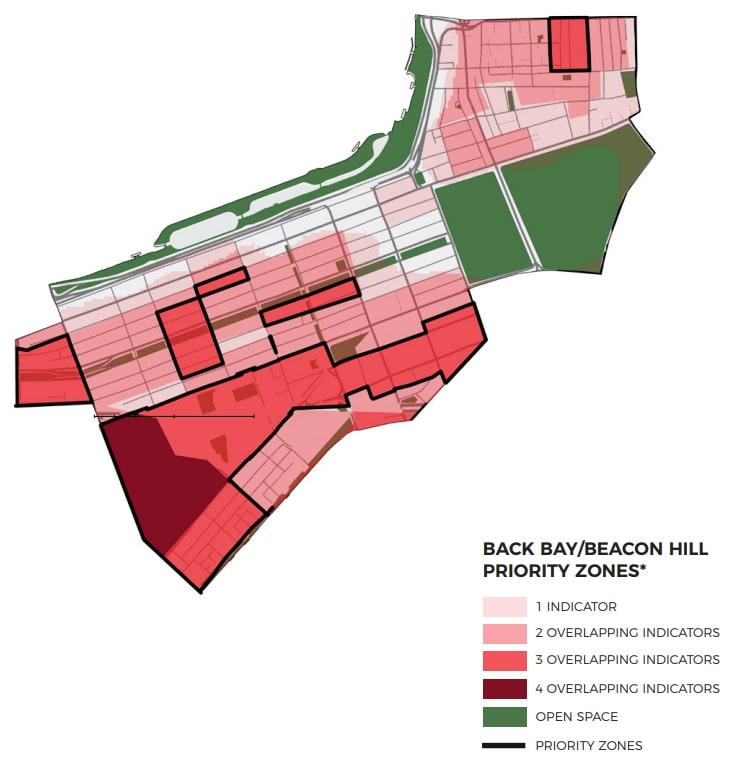

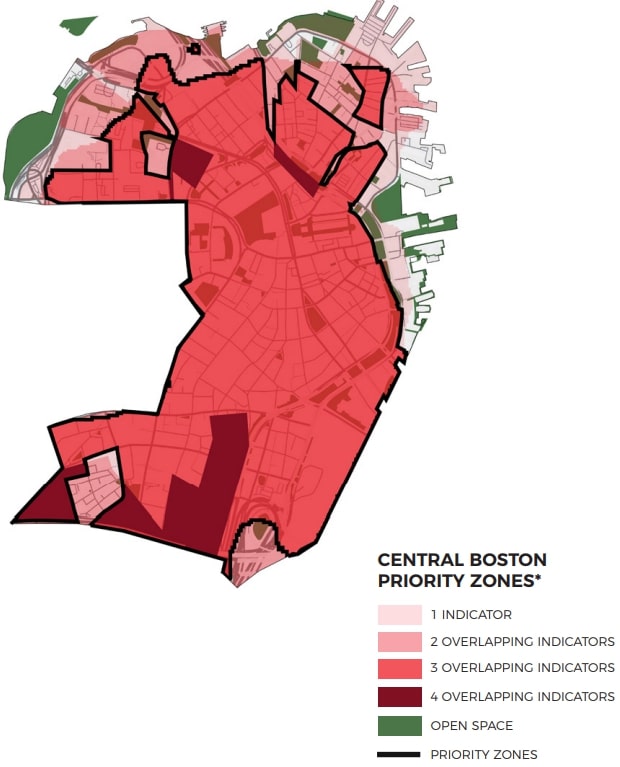

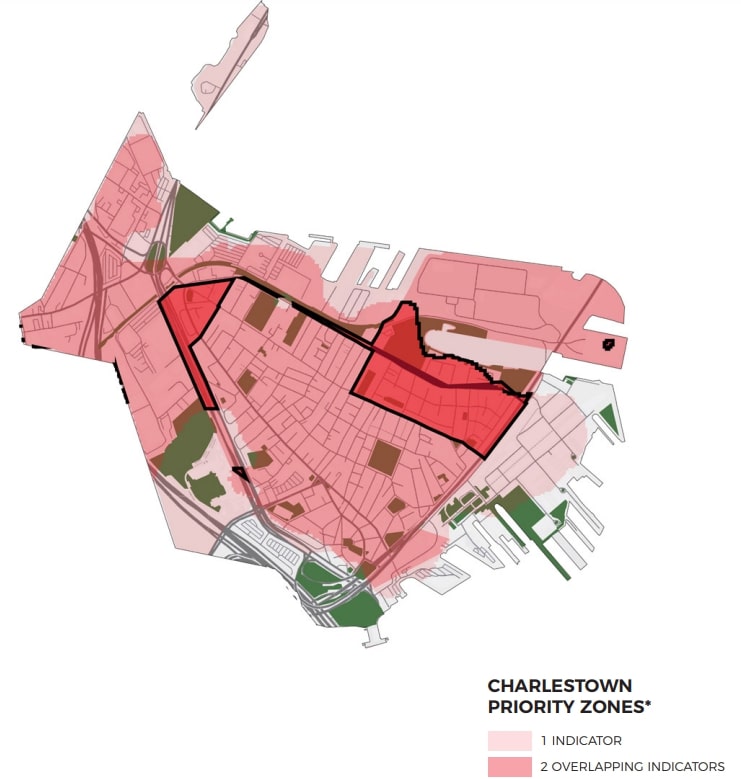

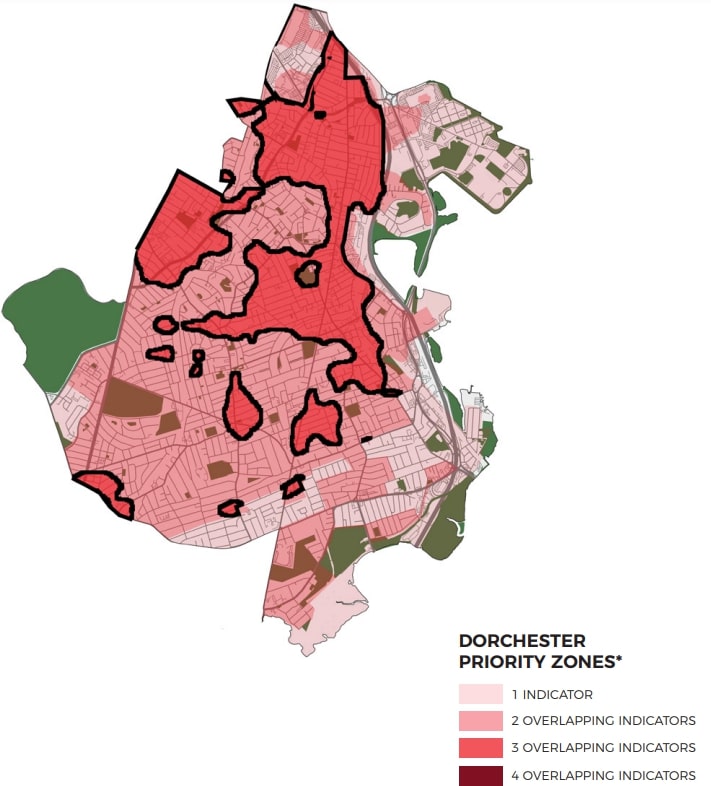

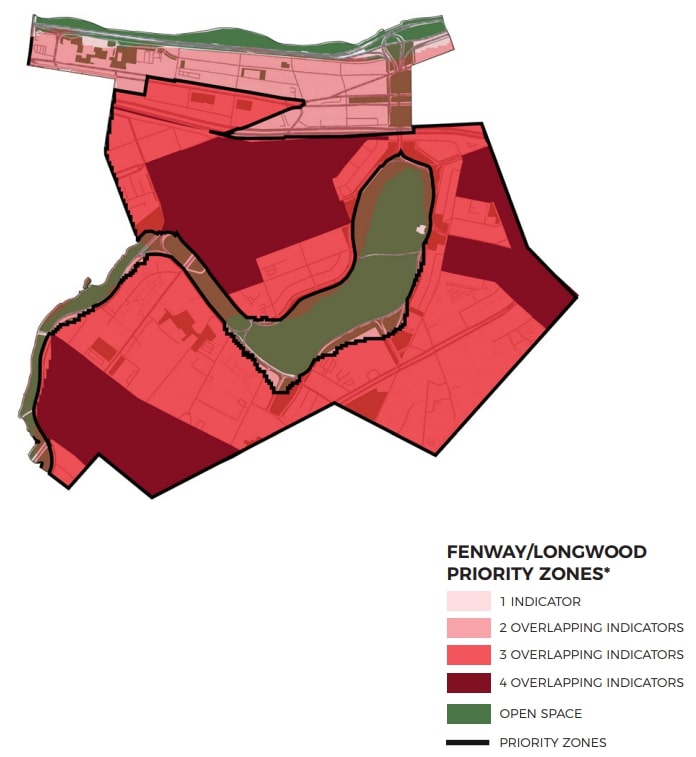

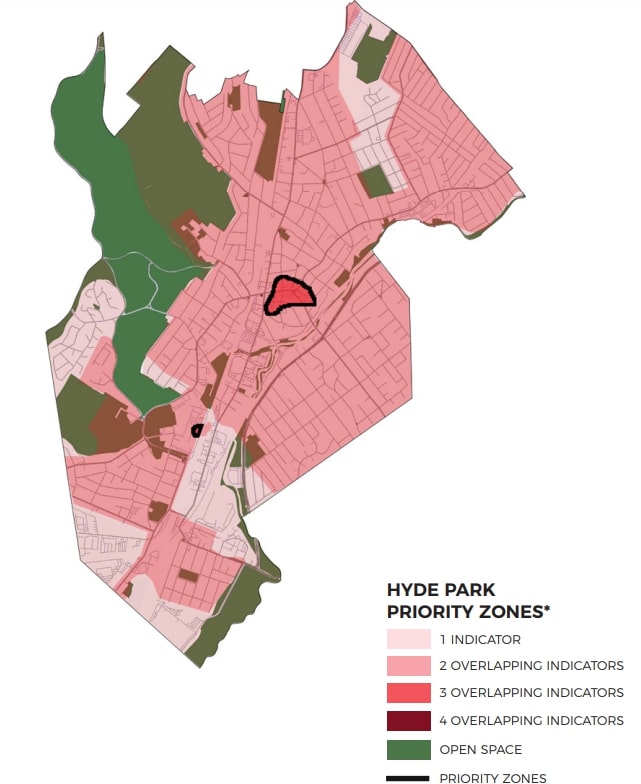

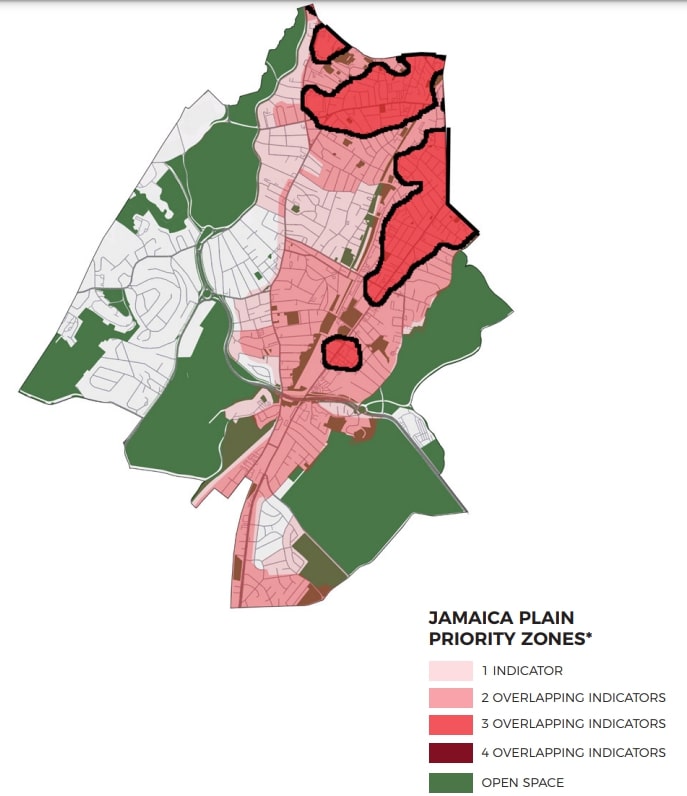

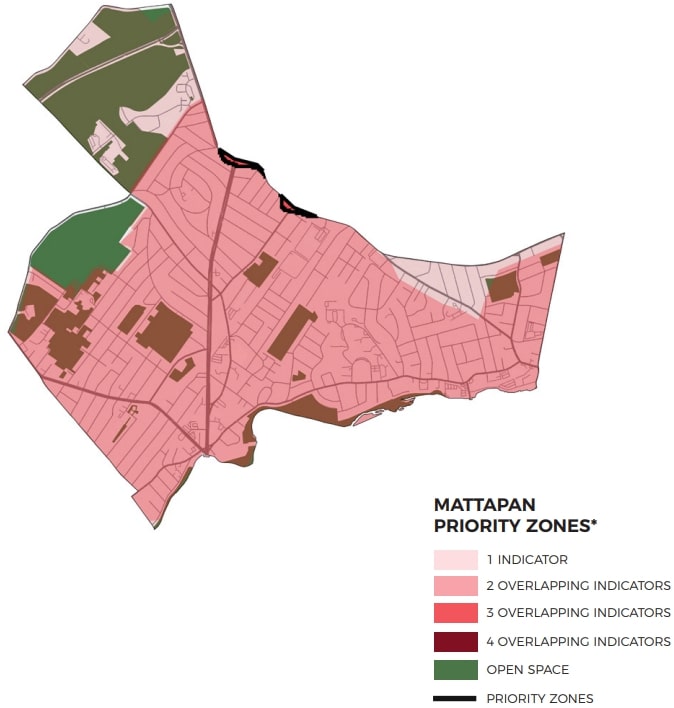

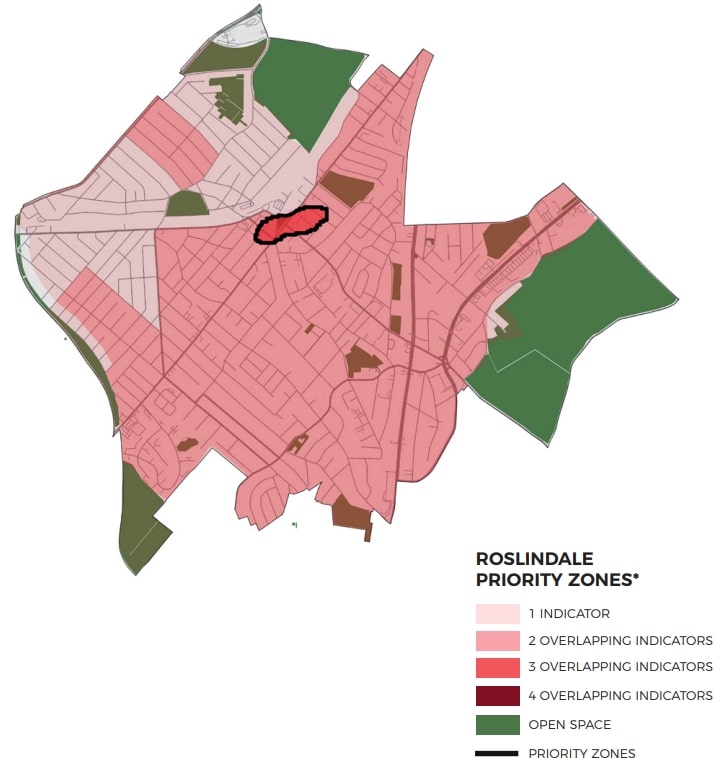

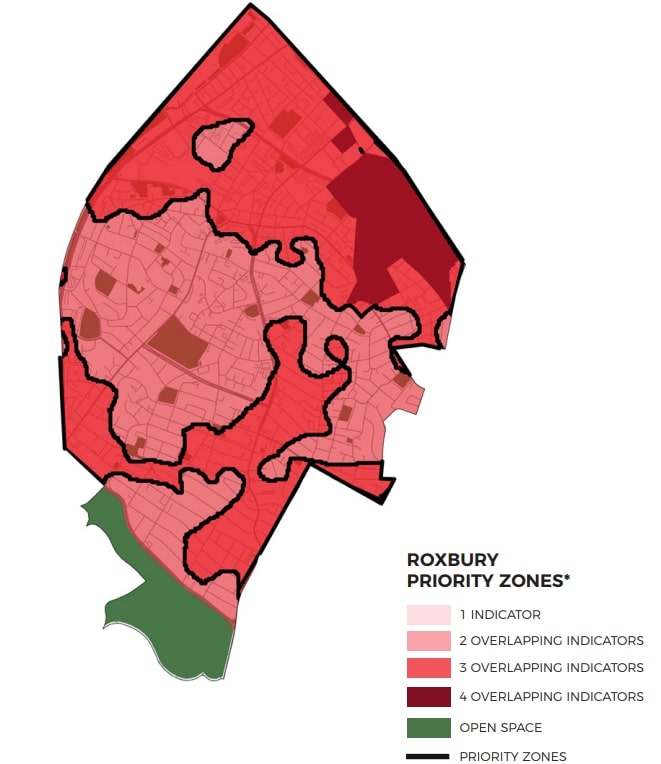

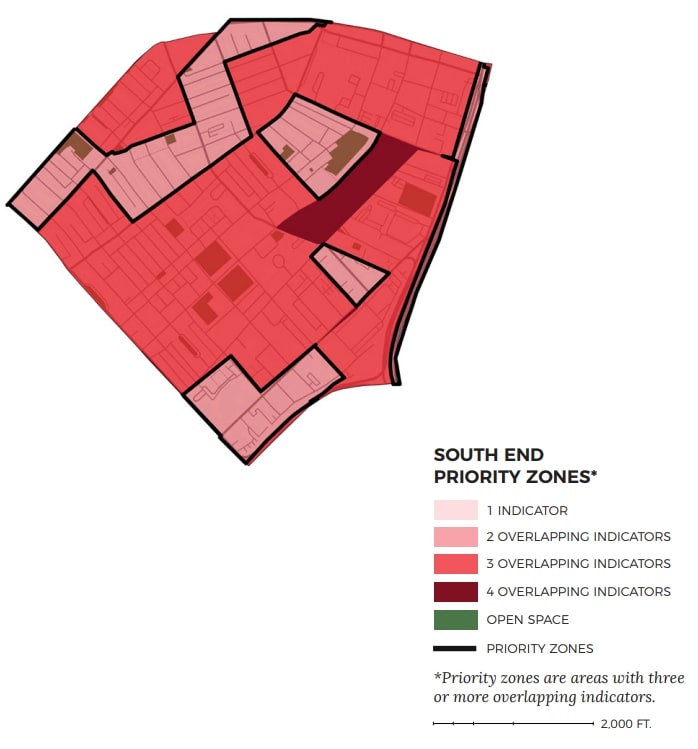

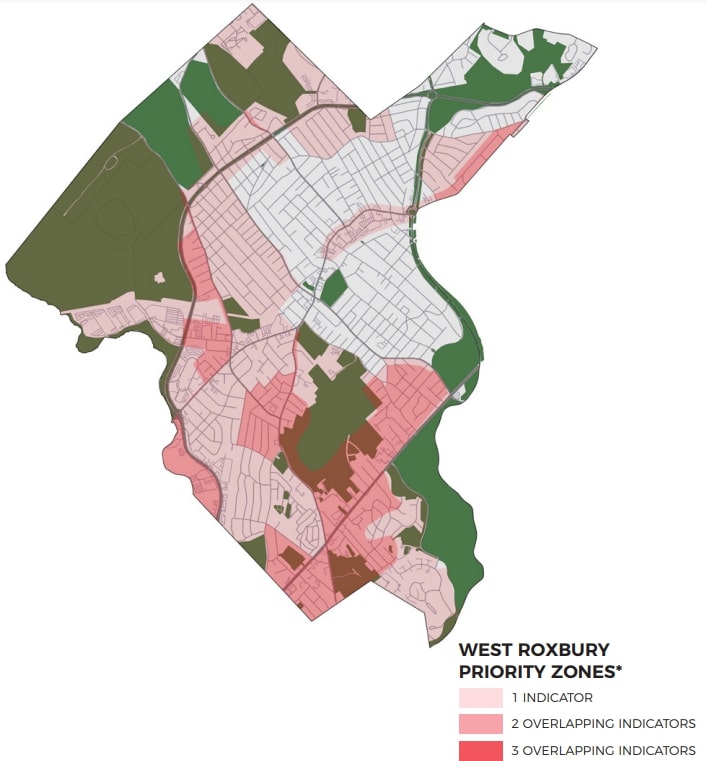

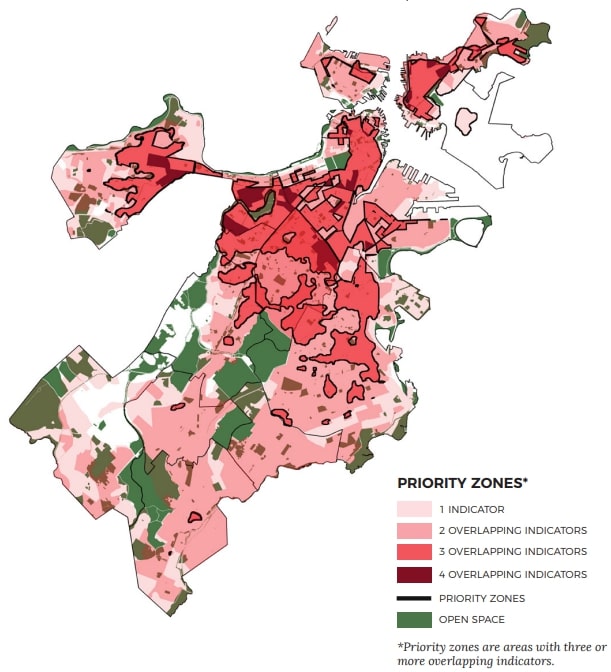

When it came to deciding where the trees are going, Mistor’s department examined the conditions of the city’s canopy and identified high priority areas for new planting. The department developed four indicators of a high priority zone: areas with canopy coverage under 10%, extended heat events in the area, environmental justice areas, and areas that had been historically marginalized through practices like redlining.

Which neighborhoods need trees the most?

These maps show areas that the city is targeting to plant additional trees. The darker the red color, the greater the need.

“If any particular area meets three of those four, we would identify it as a priority zone,” Mistor said. “Again, this is not a perfect system or something that is the only guide that we have but it does help focus us and understand where some of the most need is, again, it doesn't mean that there's an abundant place to plant trees in those areas.”

Mistor said residents can go to the Urban Forestry website to request a tree for their property or an area nearby.

Mistor also said there are plenty of ways for people to help the trees already in the ground.

“If people have their pets out there, make sure their pets aren't watering the trees, because it’s really not helpful to a tree,” Mistor said. “It is not giving it nutrients that it needs. Actually the nutrients can burn and damage the tree and especially with young trees that can cause a lot of damage.”

Mistor also emphasizes the importance of staying off of the dirt around it’s base to avoid compacting it and cutting off water and nutrients to the roots. He also said that if residents can they should try and help water a young tree still trying to get established.

“We want to make sure that these trees will be assets for the future,” Mistor said. “We can plant a tree and it doesn't provide a whole lot of benefits when we plant it. It takes 20 years to get to a size where it provides real benefits for the neighborhood. So we have to make sure that it's going to survive for that time and thrive during that time.”