Amid the tensions that brewed following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, Ava DuVernay read journalist Isabel Wilkerson’s book, “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents,” published that summer. The book, DuVernay admitted, had been sitting on her coffee table for a while before she decided to read it.

“When I finally picked it up, I was so grateful for it, because it gave me language to organize my thoughts,” she told the audience at an April 24 talk at the Harvard Kennedy School. After a second read of the book, which theorizes a throughline between racism in America, caste in India and hierarchy in Nazi Germany, the award-winning director began to see a story emerge from the pages.

So, she set out to tackle a mammoth task: to adapt Wilkerson’s 500-page, somewhat academic book into a feature film.

The thought of making a movie about caste based on Wilkerson’s book was “way too intimidating,” DuVernay said. Instead, she chose to write one “about a woman on an exploration, on a journey” and her quest for knowledge.

Released in January, the movie “Origin” follows Wilkerson, portrayed by actress Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor, as she aims to turn the kernel of an idea — that racism in America can be better understood by unpacking the caste system — into a larger oeuvre connecting all the dots.

DuVernay’s repertoire includes “Selma,” a fictionalized account of the 1965 march to Montgomery, Alabama, led by Martin Luther King Jr.; “When They See Us,” a miniseries about the Central Park Five; and “13th,” a documentary about the disproportionate mass incarceration of African Americans.

“People ask me, ‘Gosh, you write … such traumatic storylines,’ but I don’t see my work as being about trauma. I see all my work as being about triumph,” DuVernay told the audience. “And you can’t triumph if you don’t know what you’re overcoming.”

In her films and shows, she interrogates big systems, large swaths of history and policies.

“The core of it is, how did it affect people?” she said.

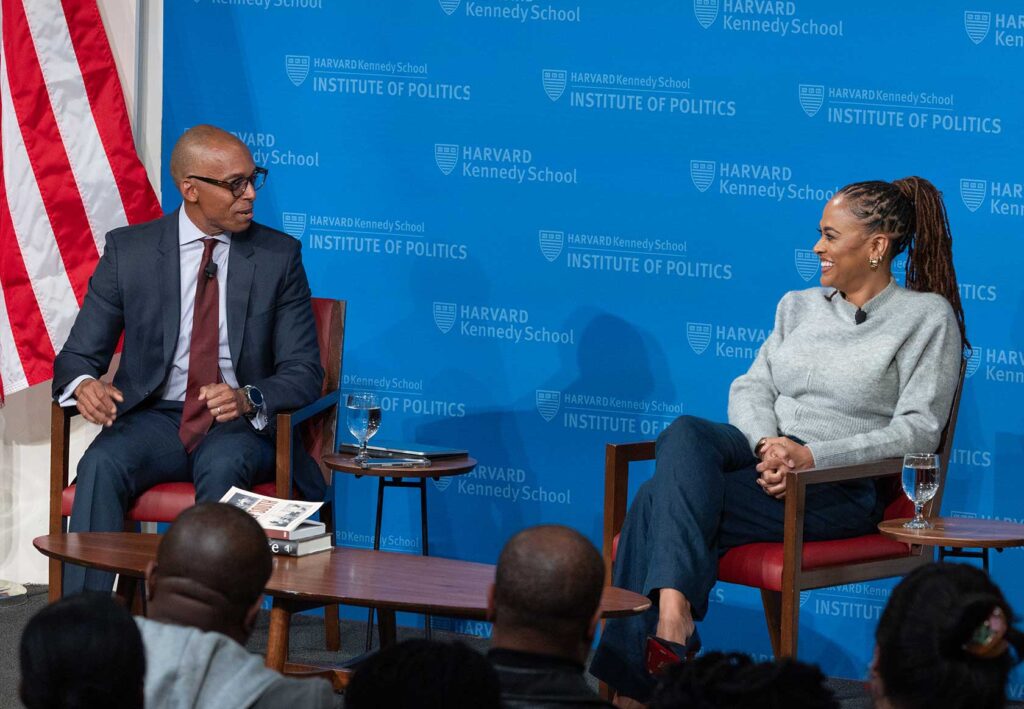

In conversation at the Kennedy School with Khalil Gibran Muhammad, Harvard Ford Foundation professor of history, race and public policy, DuVernay broke down how she drew from the more academic content of the book for inspiration while centering Wilkerson’s own personal journey.

DuVernay parallels Wilkerson’s search for answers about the past with the journalist’s own personal turmoil. Over the course of her research, Wilkerson’s husband, cousin and mother all passed away. DuVernay depicts this in the film.

“We get to love the people that she loved and lose them as she loses them, and what she’s finding and gaining during that time as well, with a trio of other love stories that she’s investigating and exploring,” she said. “And all of those collide.”

DuVernay said she was drawn to Wilkerson’s pursuit of the idea, which is front and center in the film, but the book is less about Wilkerson’s theory itself.

“Whether or not she got it right, or whether her ideas supersede others or whether it should replace others … is not what I am proposing,” DuVernay said of Wilkerson’s thesis.

Most important to the filmmaker is having an exchange of ideas with viewers, rather than talking at them.

DuVernay condensed two years’ worth of interviews with Wilkerson and 400 years of history across seven different time periods into a two-and-a-half-hour film shot in 37 days in three countries.

“Origin” features historical flashbacks of concentration camps and a book-burning in Nazi Germany, scenes from the Jim Crow South and the lives of Dalits in India who are considered the lowest on the rungs of social hierarchy there. In one notable scene, two Dalit men clean a sewer, one with his body submerged in human waste. This image, DuVernay told the audience, still plays out in modern-day India.

In another scene, a group of Nazi generals are seen discussing Jim Crow laws, essentially studying the laws to design their own system of hierarchy in Germany — a piece of little-known history Wilkerson delves into in her book. DuVernay pulled the dialogue in the scene directly from archival transcripts of the conversations.

She employed this interweaving of history and historical fiction throughout the film to create “blurred edges” that prompt viewers to ask themselves if they are watching a documentary or if the film is indeed fiction.

DuVernay also juxtaposes scenes from the Middle Passage with scenes of Wilkerson writing about that time period. “Origin,” the director said, gave her the opportunity to achieve that parallelism in a way that she “can’t do when the story is contained only to history.”

Unlike in “Selma,” the historical elements of “Origin” sit alongside the contemporary, DuVernay said, adding that the film “animates the history in a way that reminds us that it’s never far behind us and that that is a part of our present and our future.”

“Origin” is heavy, DuVernay acknowledged, yet equally “beautiful.”

“I think the film is a collection of love stories, really, and I’ve counted up to 18 love stories in the film,” she said. “And they come through small moments, and they come through story arcs that span from the first act to the last act.”