‘Ethiopia at the Crossroads’ at Peabody Essex Museum surveys 2,000 years of art

Banner Arts & Culture Sponsored by Cruz Companies

There’s only one country that can claim to be the birthplace of humanity. This country today is home to over 75 ethnicities, and is the only African nation to resist colonial rule. This country is Ethiopia.

Ethiopia is one of the world’s oldest nations and served as a crossroads of diverse cultures and religions in the ancient world. This long and rich history is now on display in Salem at the Peabody Essex Museum. The “Ethiopia at the Crossroads” exhibition, on display through July 7, is part of a traveling exhibition that originated at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore and will end at the Toledo Museum of Art.

Folding Processional Icon in the Shape of a Fan (detail). Ethiopian artist, late 15th century. Ink and paint on parchment, thread. PHOTO: THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM, BALTIMORE

The exhibition includes more than 200 objects spanning 2,000 years in five galleries. The objects range from processional crosses and ancient manuscripts to Haile Selassie’s royal cloak and contemporary collages. The Queen of Sheba is featured, along with art from Ethiopian Jews, Muslims and spiritualists.

Jesus, Mary and patron saints are prominently displayed with brown skin in religious iconography. These icons are Christian art created in an African nation whose monarch, King Ezana of Aksum, willingly adopted the religion in the fourth century, without force via colonialism and violence.

Not only can viewers see art from Ethiopia, they can also delight their senses in other ways. Scratch-and-sniff cards with scents of berbere spices, frankincense and manuscripts are available to inhale while viewing artifacts. Sounds of Ge‘ez, an ancient Ethiopic language, and music from an Orthodox church service can be heard throughout the galleries from educational videos covering these topics and more.

“Putting It Together,” from The World is 9 series by Aïda Muluneh, 2016-2019. Inkjet print. PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE ARTIST

The show is the first of its kind in America to put Ethiopia and its visual history in a global context. Pieces from Italy, Crete, Armenia and Coptic Egypt are shown in conversation with pieces from ancient and contemporary Ethiopia by artists like Julie Mehretu and Aïda Muluneh. Medieval and modern objects reference the themes of faith and revolution. What’s old is new.

Over Zoom last week, Christine Sciacca, the creator of the “Ethiopia” exhibition and curator at the Walters Art Museum, joked that she got her current position because she pitched the idea for “Ethiopia” in her interview eight years ago. COVID-19 lockdowns delayed the exhibition. Sciacca is proud to see her vision come to life, but it wasn’t without the help of the Ethiopian community in the D.C. area — the largest Ethiopian diasporic community outside Africa.

“I had my advisory committees,” she said. “They were community members, academics and college students. There were nurses, teachers and Orthodox priests who were sharing their lived experience with me.”

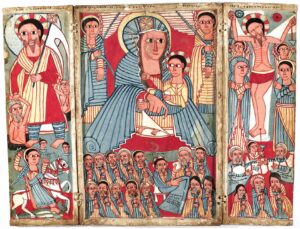

The Virgin and Child with Archangels, Scenes from the Life of Christ, and Saints. Ethiopian artist, early 17th century. Tempera on panel. PHOTO: THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM, BALTIMORE

Sciacca also used design input from community members. They wanted the exhibit to include the colors of the Ethiopian flag and lots of light, since Ethiopia represents light to them.

At Peabody Essex, curators Lydia Peabody and Karen Kramer also heeded the suggestions of community members. In the exhibition, they use colors of the flag as accents against light, cream-colored walls and shadows of church windows above the art. At times the gallery is too light, causing some of the medieval manuscripts to fade into the background.

One artist’s work that doesn’t get overlooked is interdisciplinary artist Helina Metaferia. Metaferia was born in D.C. to Ethiopian immigrant parents. On a phone call last week, Metaferia explained her personal connection to the exhibition. She interned at the Walters years ago and worked with the Ethiopian art collection. Sciacca came across Metaferia’s notes while compiling pieces from the Walters collection. The artist’s father, Dr. Getachew Metaferia, was on the academic advisory committee for the exhibit.

“We have a very unique history that is reflected in the artwork. Hopefully people get to walk away with a more nuanced understanding of Ethiopian culture,” she said. “I hope there are more [exhibitions] because I think that other artists deserve to have this opportunity, and curators deserve to have this response.”