Admissions policies for the state’s vocational high schools create disparities in access for students of color, low-income students, students with disabilities and English-language learners, a collection of community, union, and civil rights groups allege.

The Vocational Education Justice Coalition said existing admissions policies limit offers to students from protected classes in an analysis published earlier this month.

“We feel as though every student should be entitled to enroll and should have the same equal opportunity to enroll in a vocational school,” said Dan French, president of Citizens for Public Schools, one member of the coalition. “That means that whoever applies to get equal opportunity to be offered a seat.”

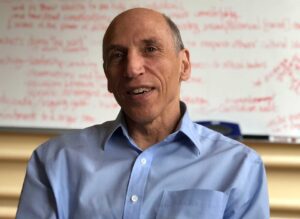

Dan French, president of Citizens for Public Schools and member of the Vocational Education Justice Coalition. COURTESY PHOTO

Currently, state guidelines require each school to submit an admissions policy. In most cases, those policies rank students based on factors like grades, attendance, discipline, recommendations and interviews. Members of the coalition say these factors are where the disparities arise.

According to the coalition, 23 of the 26 regional vocational schools in Massachusetts that had submitted data at the time of the analysis had one more category in which applicants of at least one category of protected class were offered seats at a rate of at least 10 percentage points lower than that of more privileged students. Seventeen of the schools had at least one category where applicants of a protected class were offered seats at a rate of at least 20 percentage points lower.

Regional vocational schools draw students from two or more municipalities. While the participating municipalities pay for each student attending, the schools are under the control of an independent governing board that draws members from each sending district. The governing boards determine the schools’ admissions policies. Critics say those policies have allowed the regional vocational schools to function more as college preparatory schools than as pathways to a trade.

The coalition is pushing for a blind lottery, through which all students who apply would be entered into a pool, regardless of any other factors. If more students apply than there are seats, they would be selected at random.

Steve Sharek, executive director of the Massachusetts Association of Vocational Administrators, said he worries a blind lottery would fail to sort out students who don’t have a real interest in vocational education.

“Do they have a true interest in vocational education or is it something tangential?” Sharek asked. “We want them truly to be someone who wants to be in vocational education because it is not for everyone.”

Recently, following agency reviews, the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education sent letters to four schools — Bay Path Regional Vocational Technical School, Montachusett Regional Vocational Technical School, Greater Lowell Technical High School, and Greater New Bedford Regional Vocational Technology High School — which they identified to follow up with regarding admissions processes.

Bay Path Regional Vocational Technical School PHOTO: Courtesy oF Bay Path Regional Vocational Technical School

According to the department, it plans to provide technical assistance to three of those schools to help close gaps. For the fourth, Greater New Bedford Regional, it plans to collect additional information and seek corrective action if needed.

One state dataset is at the center of the debate around how the admissions processes affect students from the protected groups. Each year DESE releases a state report with annual data around eligibility, applications and enrollment from students entering ninth grade in a vocational school’s municipalities.

The coalition pulled its numbers from that report with a focus on the statistics of how many students applied, received offers and accepted the offers to attend a vocational tech school.

Sharek points to the same data set but instead looked to numbers around how many students are eligible to apply compared to how many are enrolled — data points for which he said he opts for their lower margins of error and a more on-the-ground impact — and suggests that through those numbers, many schools seem to be doing alright when it comes to regional vocational schools nearing or meeting parity among the protected groups.

“Who’s in the pool? Who’s in the school?” Sharek asked of the data. “To me, those are the only things that matter. All the other stuff is balls and strikes; it’s all procedural stuff.”

But Dan French, who led the data analysis for the coalition, said, under the law, the procedure is the important part and looking at just the numbers around eligibility and final enrollment fails to capture a picture of an allegedly discriminatory admissions process.

“What federal law looks at is what is the process for selecting students, not whether they’re representative of sending districts,” French said.

A handful of paths toward lottery admissions

Two vocational schools in the state already have forms of lottery admissions, though neither are the fully blind lottery process the coalition is pushing for.

In Marlborough, following the 2021 legislation, Assabet Valley Regional Vocational Technical High School adopted a lottery-based policy that requires students first complete an application, interview and submit a letter of recommendation. Prospective students who complete the requirements are then submitted for the lottery, if student interest is greater than the number of seats available.

Also in 2021, Worcester Technical High School adopted a tiered lottery policy, which creates different applicant pools based on criteria around discipline and attendance.

French said he and the coalition view the altered lottery systems as a step in the right direction but worry that the requirements still introduce bias or present limitations for students looking to join the programs.

At the State House, legislation sponsored by Sen. John Cronin would require vocational schools and programs adopt a lottery system.

The original draft of the legislation called for a blind lottery but was changed as it moved through and out of the Education Committee. The legislation, as currently drafted, allows districts to consider attendance and discipline for entry to the lottery.

“When you stop rank-ordering applicants based on grades you stop disproportionately excluding them from our vocational schools. That’s the problem that we’re trying to fix,” said Cronin, who represents parts of Worcester and Middlesex counties.

Under the 2021 changes to state guidelines governing vocational school admissions, selective criteria may not exclude students by protected class unless the criteria are essential to participation in vocational — also called Chapter 74 — programs.

Cronin said he thinks the possible considerations around attendance and discipline in the legislation’s modified lotteries would present important information about the ability to participate in vocational programs, but other criteria currently included in the processes, like grades, recommendations and interviews do not.

The coalition has also met with staff from the office of Governor Maura Healey, asking her to direct the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education to change the rules around admission to create lottery policies statewide.

The Healey-Driscoll administration is committed to ensuring equitable access, said Karissa Hand, a spokesperson for the governor, and has been engaging with the coalition as well as officials, educators and stakeholders on the issue.

Efforts to expand vocational seats

Sharek points to efforts to increase seats at vocational schools as an alternative — in his mind, better — solution to the problem of who gets offers to attend vocational schools in the state.

“Right now, no matter how you do it, someone’s going to be on the outside looking in,” Sharek said. “I want every single student who wants vocational education to get it.”

Sharek and the Massachusetts Association of Vocational Administrators are pushing for a series of grants between $5 million and $25 million targeted toward regions with vocational tech waitlists.

The proposal takes the place of $3 billion in bond funding that was originally proposed in legislation. That larger sum was removed as that bill was combined into an education omnibus package.

While French said he and the coalition agree that the state needs more vocational education seats, only expanding seats doesn’t address the crux of the concerns the coalition has, which is that they view the selective admissions policies as discriminatory.

“Increasing seats in an inequitable system does not fix the inequities,” he said.

Cronin said he thinks the state needs to expand capacity, but the issue’s fix won’t come just by just adding more seats or more schools. He said he worries that just expanding capacity will attract more students who are bound for college and other forms of post-secondary education.

Instead, in a bill filed in March, he proposed an allocation of $100 million that would support the construction of annex vocational programs at comprehensive — non-vocational — high schools in the state’s Gateway cities.

In that proposal, the annex programs would expand the state’s vocational capacity with regionally-aligned programing targeted toward needs in the area — programs could focus on HVAC work in some regions, or carpentry, or plumbing in others, depending on what is most important to the region’s economic sector.

Admissions fight builds on lengthy history

According to the coalition, the issues started in 2003 when vocational school superintendents and communities lobbied the Board of Elementary & Secondary Education for a new statewide admissions policy in response to the advent of the MCAS graduation requirement.

Out of concern that their students would score low and cause the schools to be marked as underperforming, vocational tech high schools pushed for admissions policies that considered factors like attendance, disciplinary record and grades in an attempt to reach students who would rank higher academically.

A 2021 move by the state legislature to attempt to address concerns about disparities let schools set their own admissions policies, though most continued using a selective system like the one in place before. Coalition members say that change has had little impact on the landscape broadly.

Requirements around admissions are nothing new, said Wilfrid Savoie, a former superintendent at Blue Hills Regional Technical School in Canton and the self-published author of “The History of Vocational Education in Massachusetts: A Model for the Nation.”

Dating back to the inception of the system in the state, in the early 1900s, schools implemented admissions requirements for students, though the specifics of those requirements changed over the years. The throughline for the requirements was to attempt to show that a student can benefit from vocational education, he said.

Coalition members said they think the changes with MCAS in the early 2000s led to a shift away from serving students seeking to go into trades, what is generally considered the traditional course for students. Instead, they said it created a reputation for vocational tech schools to serve as another element on resumes for students looking to pursue science, technology, engineering and mathematics degrees at four-year institutions.

Finfer cited a story he had heard from Tom Fischer, executive director of the North Atlantic States Carpenters Training Fund — one member of the coalition — in which 10 students majoring in carpentry in vocational schools came to visit the statewide carpenter’s training center. When asked, all 10 said they were going to college the following year.

According to a report from DESE, a 2018 survey of Massachusetts graduates from career vocational technical education programs found that 50% of graduates went on to additional education. Just 33% entered work in a field related to their vocational studies.

Advocates said that a pathway from vocational education to work in a trade is an important pathway for vocational students to move toward the middle class without having to pay for a four-year degree.

Finfer cast admissions policies that can keep those students out of vocational schools as something that can impact middle schoolers for the rest of their lives.

“This admissions system is basically making lifetime decisions based on eighth graders’ records on grades and attendance and discipline,” he said.

Cronin pointed to a host of efforts the state has made goals — like building additional housing, constructing two bridges to Cape Cod, upgrading transportation infrastructure and decarbonizing an aging housing stock — all of which will require a strong building trades workforce.

“We can’t do that with a workforce that is smaller tomorrow than it is today,” Cronin said. “That’s the path that we’re on when our premier workforce development pathway, vocational schools, are sending more graduates to college than they are to our workforce.”