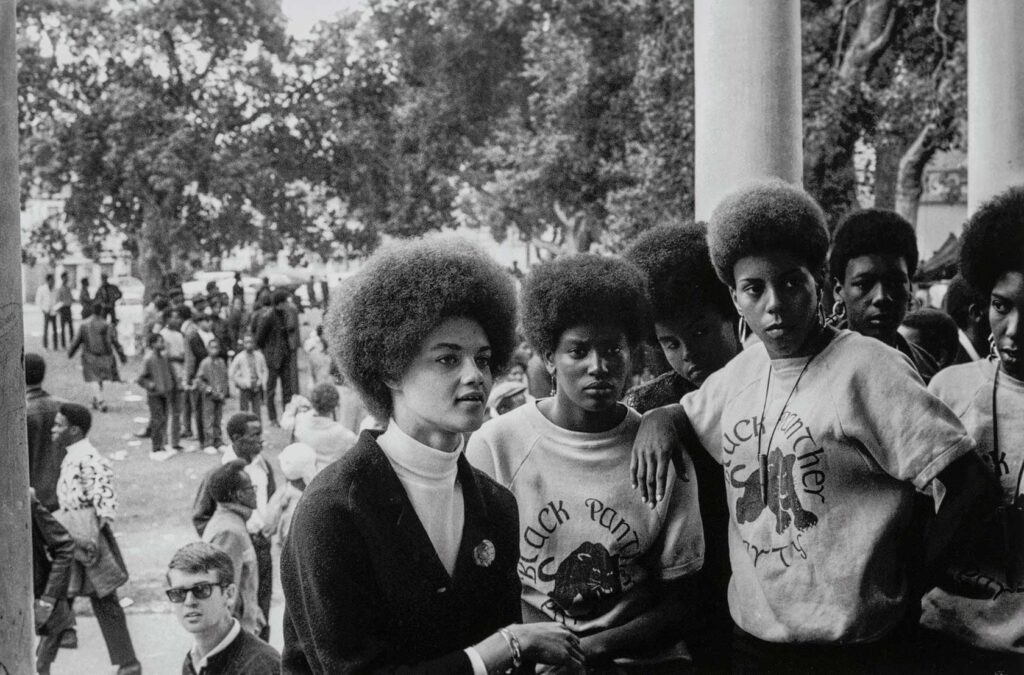

For nearly a decade in the 1960s and ’70s, photographer Stephen Shames captured the Black Panther Party, recording the critical community work and activism of the group. In “Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party,” at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston through June 24, these photographs highlight the female contingent of the party, which made up more than 65% of its members.

“Active in a number of different cities, including Boston, the female party members in Shames’ photographs are documented at work in community schools, free medical clinics, voter registration sites, community nutrition programs and elder care centers,” says MFA’s Lane Senior Curator of Photographs Karen Haas, who organized the exhibition.

Some images showcase the women of the Black Panther Party in relation to their male colleagues. In “George Jackson funeral at St. Augustine’s Church in Oakland, August 28th 1971,” Glen Wheeler and Claudia Grayson stand side by side in front of the church like soldiers standing guard over the proceedings. Behind them, funeral attendees talk in small groups.

Oakland, California: Adrienne Humphrey tests a woman for sickle cell anemia during Bobby Seale’s campaign for Mayor of Oakland., 1973. Stephen Shames (American, born in 1947)

Photograph, archival pigment print. Gift of Lizbeth and George Krupp. © 2023, Stephen Shames. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In other portraits, women work alone or in groups. In “Oakland, California: Adrienne Humphrey tests a woman for sickle cell anemia during Bobby Seale’s campaign for Mayor of Oakland,1973,” Humphrey prepares a test for a senior woman who has her arm extended. Humphrey is with a small group of other Panther members, mostly women.

The Black Panther Party launched Peoples’ Free Medical Clinics (PFMC) in 1968 to combat systemic racism in hospitals and private practices. These centers primarily provided services like first aid, blood pressure testing, and screenings for tuberculosis, diabetes and lead poisoning. In the early 1970s, these clinics began screening for sickle cell anemia, a condition primarily impacting those with African ancestry.

PFMCs were just one part of more than 60 community programs developed by the Panthers. These programs included free clothing, shoes and food drives, dental care, education and youth institutes, ambulance services and much more.

Shames is a white photojournalist and a Cambridge native, not the figure one would expect to be an official photographer of the Black Panther Party. While a student at University of California-Berkeley, Shames met party co-founder Bobby Seale at a march opposing the Vietnam War. Seale was moved by the intimacy of Shames’ portraits and brought him on to photograph the everyday inner workings of the party.

Palo Alto, California: Woman with a bag of food at the People’s Free Food Program, one of the Panther’s survival programs., 1972. Stephen Shames (American, born in 1947) Photograph, archival pigment print. Gift of Lizbeth and George Krupp. © 2023, Stephen Shames. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Though Shames’ story is interesting and his role is important, “Comrade Sisters” appropriately keeps the focus on the subjects of the photographs — the Black women whose significant contributions to the party often went unnoticed.

“I am particularly drawn to the dignity and power in Shames’ portraits of individual figures — some of them well-known, like Kathleen Cleaver, Ericka Huggins and Afeni Shakur (mother of the late rapper Tupac Shakur), but many whose names were not recorded at the time and remain anonymous,” says Haas. “There is a palpable sense of trust between the photographer and the subjects in his pictures.”

Shames captured all sides of the Panther experience, from the daily community work and empowering speeches to the emotional highs and lows of activist work. For as much challenge as there was, Shames also depicts the great joy. In “Oakland, California: Black Panther member Ericka Huggins laughs with comrades after the Black Community Survival Conference,” Huggins has her head tilted in raucous laughter. Her closed eyes and widespread smile radiate joy and promise.

“The ‘Comrade Sisters’ photographs continue to feel very relevant because, on the one hand, the coalition-building and many of the social initiatives begun by the BPP were so groundbreaking and critically important that they continue in many places,” says Haas. “The most unfortunate aspect is, of course, that there is so much work yet to be done as far as achieving equality.”