In Boston, the mayor has ultimate authority for the management and administration of public education. A substantial portion of the mayor’s time and about 40% of the city budget are spent on education issues. Now, several city councilors have put forth the plan shift to an elected school committee to run the school system, which would weaken the power of

the mayor.

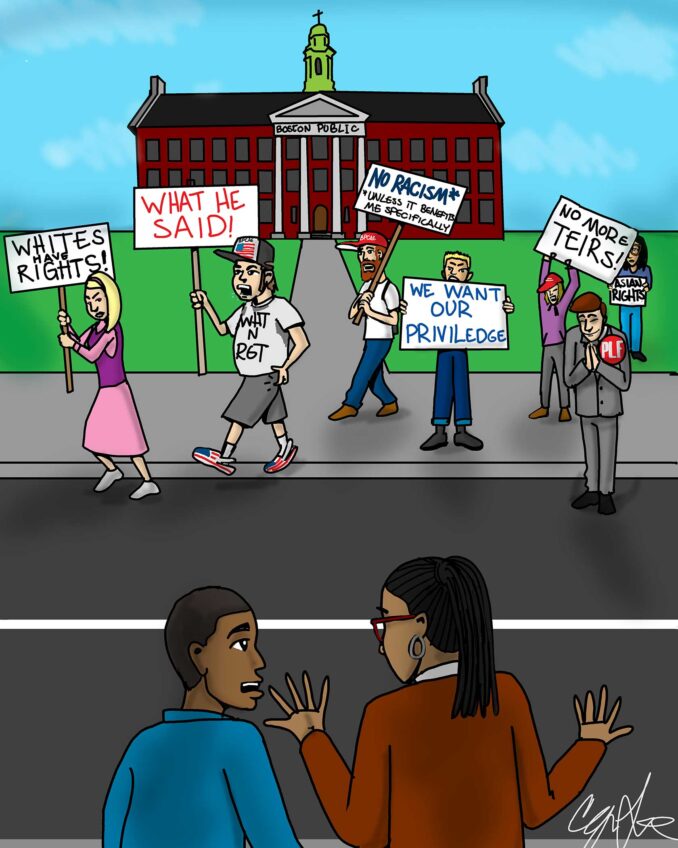

Such a change would be politically disastrous. No one old enough to have been in Boston during the school discrimination of the 1970s would be likely to support the return of the elected school committee. Back then, the school committee functioned as a bigoted bloc to prevent the mayor from complying with the laws that opposed racial discrimination in education.

Election to the school committee created an opportunity for the politically ambitious to obtain visibility in preparation for a future run for a more significant post. Louise Day Hicks demonstrated how well the system works. As an unnoteworthy lawyer who callously espoused the cause of racial discrimination in public schools, she was able to win the congressional seat vacated by the retirement of John W. McCormack, the former speaker of the U.S. House.

White racists on the school committee ignored the relevance of the Massachusetts law established in 1855 to outlaw racial discrimination in public schools, and assertively violated the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. While the Black population was not large enough then to combat the school committee politically, Blacks turned to the courts.

The case of Morgan v. Hennigan was filed in 1972, and Federal District Court Judge W. Arthur Garrity issued an outstandingly well-researched opinion in 1974. His ruling found that many Black elementary schools were overcrowded and that Black schools violated health and safety standards and needed repairs to meet city standards. Black schools’ $240 per-pupil spending was $100 less than that for white schools, and there were deficiencies with teachers’ experience and student tracking.

When the recalcitrant school committee refused to take steps to remedy the violations pointed out by Judge Garrity, he was forced to establish a school busing system to assure that the public schools were racially desegregated. It was considered that the violations imposed on Black students would be eliminated if a substantial number of white students were also in the same schools.

For good reason, Black community activists thereafter directed their efforts to the mayor and the state board of education. In 1985, Laval S. Wilson was appointed as Boston’s first Black school superintendent, and in 2007, Dr. Carol R. Johnson became the second. This was accomplished under pressure, without the cooperation of an elected school committee.

The experience of the 1970s establishes that school committees do not necessarily create greater democratic input for educational ideas. An initial instinct is to question the wisdom of providing a platform for restrictive and alien education ideas, such as those gaining ground in Florida and Texas. Boston has administrative and managerial problems that are best resolved at the executive level.

The primary democratic clout of Boston’s Black community is to organize to be an effective element in the election of the mayor. At that time, mayoral candidates will have to account for their plans for education.

City councilors should not propose such a major change without informing the electorate of the pros and cons of restoring the school committee structure that has already, through its own misconduct, lost its reputation.