The country, and especially those of us with loved ones in Florida, anxiously watched hurricane Ian’s landfall. We watched in horror its winds like giant fists pounding homes to rubble, its storm surge sweeping into houses and drowning those trapped inside, and its power outages suffocating residents who need oxygen machines. Rightfully, President Biden is traveling to Puerto Rico and Florida to see the devastation from two storms, offer condolences for the dozens who died, and pledge support and relief.

In Massachusetts alone, from Dec. 1 of last year to March 1 of this year, a storm surge of novel COVID variants swept away the lives of 3,723 people. Unlike Ian, this was no natural disaster: We were warned, we knew what was coming, and we knew what to do. Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley sent a letter to Gov. Charlie Baker on Dec. 21, 2021 asking him to implement measures to protect the COVID-brutalized communities she represents. These measures, to protect frontline workers, Latino and Black communities, residents in crowded housing and those at risk of eviction, had been demanded by 36 community organizations in our state, as well as 130 medical and public health experts and 14 state legislators, including Rep. Liz Miranda. (I participated in writing this COVID-19 winter Action Plan.) At that point, Massachusetts had already registered ~20,000 COVID deaths. We knew who was dying: In the first year of the pandemic, Black and Latino Massachusetts residents had over threefold age-adjusted death rates compared to white residents. Gov. Baker ignored the request.

A hurricane made of wind and water is impossible to ignore when the power goes out and faucets run dry. A COVID storm surge that sweeps away a thousand-fold more lives, in hospital rooms out of public view, is easily ignored by those that know they remain on safe high ground. For Black and immigrant communities, the pandemic is an ongoing, traumatic ebb and surge of recurrent illness, disability, bereavement, widow- and orphanhood. In wealthy communities like Newton, Weston and Swampscott where our policymakers, public commentators, and the preferred medical experts of our elected officials reside, COVID has certainly inflicted deeply mourned losses; but largely, the experience of the pandemic there has consisted of inconveniences, concerns about the effects of school masking on child development, and opportunities for career advancement and financial gain.

The pandemic experience of frontline workers and Black and Latino communities is on a different planet from that of most policymakers, their advisors, and the medical and public health experts they select to advise them. This fact barely registers in the public discourse. Even less discussed is the finding of several studies, that when they learn about the far higher pandemic toll in Black and Latino communities, many white Americans become less supportive of COVID precautions.

“Reading about the persistent inequalities that produced COVID-19 racial disparities reduced fear of COVID-19, empathy for those vulnerable to COVID-19, and support for safety precautions,” the authors of one of these studies wrote. If this reduced fear of COVID-19 and reduced support for safety precautions is prevalent in the communities surrounding our policymakers and their chosen medical experts, what is the effect of these attitudes on the COVID policies at our city, state and federal levels?

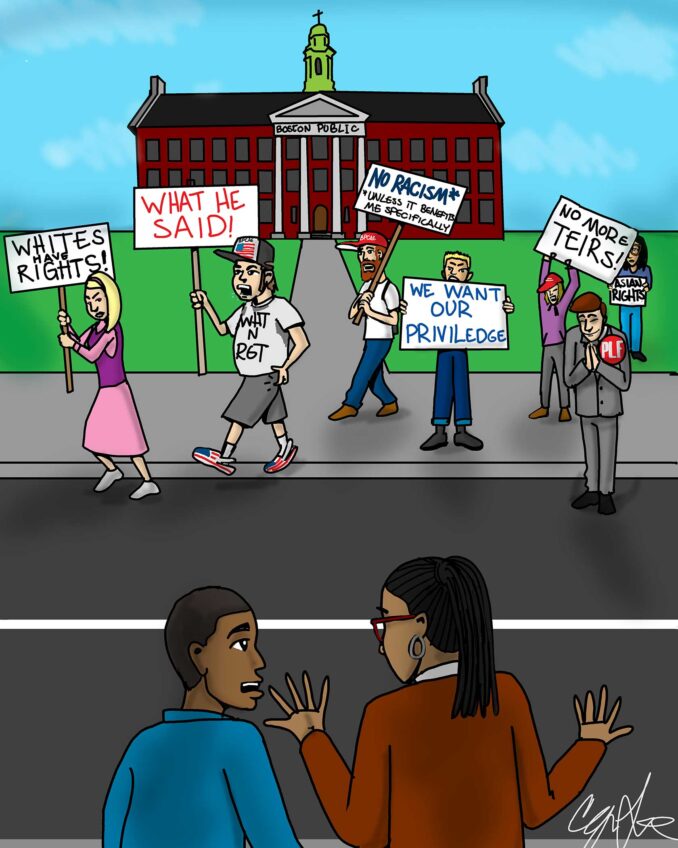

This is where representation matters. School masking is a stark example. In the spring of this year, wealthier Boston-area cities like Cambridge and Brookline dropped school mask mandates, while Boston and Chelsea continued them. A study co-led by Boston Public Health Commissioner Dr. Bisola Ojikutu showed that COVID infection rates in Boston and Chelsea schools were significantly lower than in the surrounding, higher-income cities where masks became optional. Dr. Ojikutu is out and about in Boston communities and is aware of the fact that many families of Boston Public School students prefer community-level protections. In this way, representation of Boston’s Black community at the top of the Public Health Commission protected thousands of Boston children and their families from COVID infection and eventually from illness, long COVID, and perhaps death.

Elected officials and policymakers inevitably bring their personal observations and the sum of the attitudes of those around them to their work. They typically choose advisors and experts who reflect their own preferences, spoken or implicit. Some experts who wish to be players shape their advice accordingly. Preferences of powerful institutions’ leaders, be they in business, finance, medicine or education, inevitably impact pandemic decisions. And in the general public sphere, white Americans’ voices and wishes are heard and attended to far more than those of other communities. These forces converge as massive barriers against protection of those in our communities who are at highest risk.

For the current impending COVID fall and winter surge, the CDC and the White House COVID advisory team, both led by Newton residents, have abandoned COVID protection of the highest-risk members of our communities, to the point of revoking universal mask requirements in hospitals and nursing homes. This is where representation matters. Congresswoman Pressley and Rep. Miranda know how COVID remains a deadly slow-motion hurricane in the communities they represent, and they will stand up for their constituents. Dr. Ojikutu’s policies are informed not just by her outstanding medical expertise and intellectual brilliance, but also her knowledge of the Boston communities she spends time in.

To save lives in the coming winter COVID storm surge, we will need representation. We also need awareness and advocacy. Faith-based and grassroots organizations have been doing heroic work to protect their communities from COVID and need support. How does the pandemic end? We don’t know. But the more of us who are alive and healthy, the more will be here to find out.

Julia Koehler is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital and associate professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School.