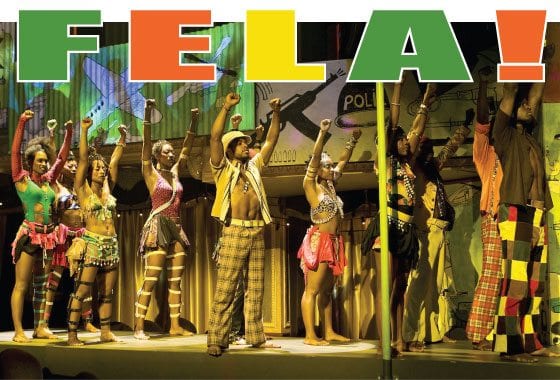

Stirring spirit, pulse and pelvis, the musical “Fela!” brings the grit and intoxicating verve of Fela Anikulapo-Kuti and his music to Broadway.

As jubilant dancers gyrate to a propulsive Afrobeat score, the production transforms the Eugene O’Neill Theatre into Kuti’s legendary Shrine nightclub in Lagos, the capital of Nigeria. Here, he waged his populist, Pan-African campaign of personal and political liberation and forged the pulsating, hypnotic grooves and smoldering horn solos of Afrobeat.

Amid the stately theater’s chandeliers are disco balls and strings of white lights. Its walls are a collage of images that evoke Kuti’s world, including political posters, tribal masks, and portraits showing a pantheon of liberators, from Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and Eldridge Cleaver to his mother, Funmilayo, a vigorous crusader for women’s rights.

Directed and choreographed by Bill T. Jones, the production restages and expands the original off-Broadway version, a brief, sold-out run in 2008 that received this year’s Lucille Lortel Award for Best Musical.

“Fela!” evokes the complex, contradictory character of its subject, a charismatic, pot-smoking libertine who revered his mother and suffered for his defiant opposition to Nigeria’s repressive military regime.

Set in his private compound, the Kalakuta Republic, which included a commune and recording studio, the production recreates Kuti’s extravagant, decadent and dangerous world.

Jones and Jim Lewis wrote the book for “Fela!” which begins in 1977, after government soldiers torched the compound, beat Kuti and his followers, raped his wives, and threw his 82-year old mother from a second-story window, causing injuries that led to her death.

The siege failed to break Kuti. Expelled from his country, Kuti briefly stayed in Ghana but returned the following year, formed his own political party, and twice ran for president. When Kuti died of AIDS complications in 1997 at age 58, one million people attended his funeral. His musical legacy has endured, spawning countless bands, and family members still operate the Shrine.

Members of Kuti’s prominent Nigerian family have shared his sense of mission if not his life style. A cousin, Nobel Prize recipient Wole Soyinka, was imprisoned for challenging Nigeria’s corrupt post-colonial government. As health minister, Kuti’s brother Olikoye Ransome-Kuti (1927-2003) revolutionized health care in Nigeria and bravely used Fela’s death to expose his country’s AIDS crisis.

Kuti’s parents offered him the same elite education that they gave his siblings. But while in London for graduate school, Fela discovered jazz and RandB and studied music instead of medicine. Back in Nigeria, he forged Afrobeat, melding diverse influences to create a post-colonial vein of music with authentic African roots. He replaced his middle name “Ransome” with the Yoruba “Anikulapo,” meaning “he who carries death in his pouch.”

As directed by Jones, every element in “Fela!” transmits the charisma and power of Kuti and his music.

“Fela Kuti is a sacred monster, and no progressive, democratic-leaning society should be without one—this provocateur, this enfant terrible,” Jones told The New York Times.

Mortality has shaded much of Jones’ choreography since 1988, when his partner in dance and life, Arnie T. Zane, died from an AIDS-related illness. Jones has continued to lead the dance company that the two founded in 1982. In 1994, he received a MacArthur “Genius” Grant and in 2007, his choreography for “Spring Awakening” won Tony and Obie Awards. “Fela!” is his Broadway directing debut.

The production combines intoxicating dancing and music with wizardly stagecraft. Marina Draghici’s set and costumes interplay seamlessly with Peter Nigrini’s video design, the wrap-around sound by Robert Kaplowitz, and lighting by Robert Wierzel that can highlight a dancer’s haughty arched brow or add a neon charge to a panorama of dancers as they leap into the aisles.

Conveying the casual hipness of a house band while churning out burning solos and pulse-thumping percussion, the show’s ten musicians perform on stage behind the ensemble. Most are members of Antibalas, a Brooklyn-based Afrobeat collective whose leader and trombonist, Aaron Johnson, is music director of the production. He and the group’s trumpeter, Jordan McLean, mined old Fela tracks to arrange the show’s music.

The show’s brilliant 19-member ensemble features ten stunning female dancers, attired by Draghici in funky, Afrobeat style. Their richly patterned batiks and cowry shells are complemented by bold body paint and fantastical braided coiffures designed by Cookie Jordan. The dancers stand in for Fela’s 27 wives, women he called his “queens.” While moving with phenomenal heat, power and athleticism in tiny skirts that expose their swiveling hips, they remain cool, self-contained goddesses.

But the axis around which the show turns is the commanding figure of Kuti himself, alternatively performed by Sahr Ngaujah or Kevin Mambo. Ngaujah received an Obie Award for originating the part in the Off-Broadway production. By all accounts, he fully conjures Kuti’s insolent and electrifying presence. On the night of this review, Mambo performed the demanding role flawlessly, if with a hint of vulnerability.

As Kuti, each actor is almost continually on stage throughout the two-and-a-half hour show, singing, dancing, narrating, and in between, taking drags from a joint or playing a saxophone solo to punctuate his taunting political commentary. Supertitles translate Kuti’s lyrics, which he delivered in the patois of his country’s urban poor.

Unfolding like sets at his club, the show portrays episodes in Kuti’s life and inventively stages selections from his vast musical repertoire, which includes 70 albums.

The production begins with a compact history of Afrobeat and Kuti’s musical education, “B.I.D. (Breaking It Down).” The brilliant medley samples his diverse influences, including Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Frank Sinatra, James Brown and Chano Pozo as well as a traditional Yoruba chant, a hit by Highlife king E.T. Mensah, and an Anglican hymn by his grandfather, J.J. Ransome-Kuti, a revered minister and master musician. As his grandfather’s photograph appears, Kuti says, “I loved the source but hated the music.”

In another episode, Kuti’s education continues in America, where Sandra Isidore, seductively played by Saycon Sengbloh, introduces him to the Black Power movement in a sizzling duet.

Other scenes stage the siege on Kuti’s compound and his wedding. As he summons each queen by name, she struts into the circle surrounding him in her signature style—one is sassy, another aloof, still others imperious or doting.

In the show’s one Broadway-style mega spectacle, Kuti visits his mother in the afterlife. Dressed in a white caftan and crown-like gele head wrap, Lillias White is a regal and warm Funmilayo and she sings her part with soul-stirring grandeur.

After this slow-motion tableau, the show resumes its crackling Afrobeat pulse, rekindling Kuti’s call to a revolution rooted in heart, mind and swiveling hips.