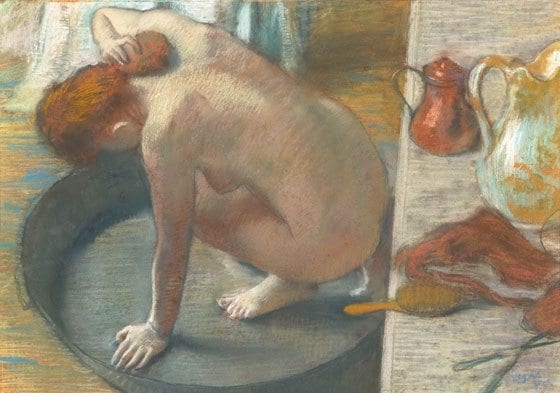

“The Tub,” 1886, Edgar Degas (French, 1834 -1917) Pastel Paris, Musée d’Orsay, bequest of Comte Isaac de Camondo, 1911, © Photo Musée d’Orsay/Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Noted French artist Edgar Degas’ exhibit at the MFA displays his talent for capturing the human form

When the great French painter Edgar Degas was starting out, he sought advice from a revered master, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. The elder artist told him, “Draw lines, young man, draw lines.”

Abundant evidence that Degas took his advice is assembled in the ravishing exhibition “Degas and the Nude” on view through Feb. 5 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). Organized by the MFA and the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, the exhibition is the first to focus on the artist’s career-long exploration of the human figure.

The MFA is the only U.S. venue of the exhibition, which presents 160 works — 140 by Degas and 20 by artists who were his influences, contemporaries and successors. Drawn from more than 50 lenders throughout the world, many works are on view in this country for the first time. The exhibition was jointly curated by the MFA’s George T.M. Shackelford and Xavier Rey of the Musée D’Orsay, where it will be presented from March 12-July 1, 2012.

The first galleries begin in the mid-1850s, when Degas, in his 20s, was copying old masters in Paris and Florence and aspiring to a career as a history painter. Alongside his ambitious oils of Spartan athletes and a scene of war in the Middle Ages are works by artists he admired, including Francisco Goya. Two prints from Goya’s satirical depictions of human monstrosity, “Disasters of War” (1810-1814), show naked bodies dangling from tree limbs and strewn on the ground.

A Degas oil painting, “Interior” (ca. 1868-1869), offers an early glimpse of his ability to use chiaroscuro effects of light and darkness to heighten a human drama. Here, lamplight falls on the glistening taffeta of a woman’s dress as, standing in shadow, a man looks on. Although it is the only work on view with fully clothed subjects, the painting bristles with erotic tension.

Nearby are the preparatory nudes Degas sketched for these oils. In a language of lines, Degas conveys human vulnerability. Some of these early gestures — arms raised in self-defense or opposition—recur in his later works.

Already, we can see Degas focus on the fundamentals that will animate his career: the use of line, light and shadow — and later, color — to render the truth of the human body.

These elements are at play in the absorbing series of monotypes — single, black-and-white prints —he did of brothel scenes in late 1870s. In one, “The Serious Client” (1876-77), a Charlie Chaplain-like male is welcomed by a trio of fleshy ladies, their faces and bodies subtly expressing amusement, appraisal and invitation.

Lit by lamps, candles and fireplaces, the candid, intimate scenes vary from cartoons to nocturnal glimpses of women alone, together or with clients. Compelling in their gritty realism, the images convey respect and even sympathy for their world-weary subjects.

Some of his most affecting monotypes are rough-hewn, earthy images, In “La Toilette” (ca. 1880-85), a bulky woman squats as she performs her morning ablations. Others are endowed with a lyrical delicacy. “Girl Putting on Her Stockings” (ca. 1877) shows a slender figure softly framed by the drapes and folds of her bedding.

As he explored the nude figure, Degas made inventive use of media that lend a tactile immediacy to his images. He crafted the monotype prints by wiping layers of ink off the etchings he drew on metal plates, using his fingers, a rag or the butt of his paintbrush. Later, he hand-colored his monotype prints with pastel chalk. It was as if he wanted to touch his subjects rather than mediate the process with a brush. Inevitably, in his quest for immediacy, he turned to sculpture, and began modeling his nude figures in wax.

The same unsparing, attentive eye Degas brought to his scenes of prostitutes going about their daily lives he turned to rendering women in their bourgeois homes as they bathed and washed themselves.

He renders their natural shapes and movements with bold, dynamic lines as — often with awkwardness — they climb in and out of tubs. His light and shade effects endow their curves with three dimensions, as if he were molding each woman’s body in his mind. Even the large and ungainly figures that make their way into his pastels and monotypes have dignity, loveliness and vulnerability.

One after another, his mid-and-late career monotypes, pastels, charcoal drawings and sculptures render ordinary women as they perform their most intimate daily routines. Degas does not idealize their bodies. Instead, he renders each woman with physical accuracy and warm immediacy — often with what look like rapidly executed strokes of chalk.

In “La Toilette” (1884-86), a richly colored pastel over monotype, morning sunlight caresses the woman’s back as she bends toward the sink, heightening the lines of her body, the round washbowl and the long verticals of drapes.

A friend of Degas, the American painter Mary Cassatt, takes a different approach to the same scene in her exquisite print, “Woman Bathing” (1890-91). Cassatt’s version is more akin to the Japanese printmaking tradition admired by progressive artists of the day, including Degas, for its compositional elegance and linearity. Her deliberately flat, almost depthless composition focuses on the colors, lines and patterns of the scene, which interlock like tiles. We delight in its cool serenity. In contrast, the more textured and less formal image by Degas pulls us in with its sensuous immediacy.

As the exhibition moves into such mid-and-late career works by Degas, it gathers astonishing momentum. Displayed in great abundance and variety, they render the human figure with intimacy and a nearly abstract sense of form. With charged lines, electrifying colors and warm naturalism, the works surge with energy.

In his later years, as his eyesight weakened, Degas increasingly added sculptures to his repertoire of nude renderings. A wall-length vitrine shows seven bronzes of dancers in a variety of poses. Flanking this display are two drawings of raw power, the charcoal “Three Nude Dancers” (ca. 1895-1900) and “Dancers, Nude Study” (ca. 1899) a charcoal with pastel tints.

Another vitrine shows a quartet of sculptures in which a nude executes four variations of a difficult pose, her torso twisted and her body balanced on one leg. In the nearby pastel “After the Bath” (1895-1900), the subject assumes the same contorted pose, the curves of her arm and torso bathed in light.

Here is a mature artist, ceaselessly striving to capture the reality of the female figure in motion.

Among the eloquent works by Degas in his later years are nudes by artists he influenced, including painter Paul Gauguin and sculptor Auguste Rodin as well as younger artists such as Pablo Picasso, Pierre Bonnard and Henri Matisse.

In his last decade as an artist, Degas was still captivated by the challenge of rendering the live human figure. Instead of the idealized classical figures he studied in his youth, Degas created monumental images of ordinary women, imbuing each with the immediacy of a study and the complex allure of art. His images still radiate fresh physical and emotional truth today.