Deyaha Moussa was a Muslim kidnapped in West Africa, purchased in Saint-Domingue by T.H. Perkins of the eponymous School for the Blind, and who witnessed the Haitian Revolution combust. Perkins’ brother trafficked Moussa to Boston in 1793. He died in 1831 and now rests anonymously in Mattapan under a giant Celtic cross.

For months, I’ve contemplated Moussa’s journey to Mattapan and the role the Perkins family played in transplanting him there. Thomas Handasyd Perkins may be remembered as a Boston philanthropist, but he was a scoundrel. Perkins’ wealth largely originated from slave trading and opium smuggling. His legacy required whitewashing, and readers of the 1927 History and Genealogy of the Cabot Family get a heaping dose of reputation laundering; this book is where we find Moussa’s story.

The dubious account of Perkins purchasing Deyaha begins under a subheading titled “Moussa the Faithful Slave.” The genealogy notes, “T. H. Perkins happening to pass by” a Saint-Domingue slave market, “observed [Moussa dying], remonstrated with the slave-dealer on his inhumanity … and sent the unfortunate African to the hospital.” While it’s easy to believe that a person who recently suffered the middle passage required recuperation, the “Perkins as a humanitarian who happened by a slave market” spin is laughable; Perkins engaged in slave trading for another eight years.

Whatever the true story of that first encounter in Haiti, we see evidence that the Perkins family thought quite fondly of Deyaha. In this same account, the author recounts an 1831 obituary that both fleshes out his African life and notes Moussa’s “warm attachment to all of the members of the household, and of the esteem in which he was held … for his honesty, independence of character and warmth of heart. “His remains,” says the same notice, “were yesterday deposited in the family vault under St. Paul’s Church, by the side of those of his late master, who was fondly attached to him.” It is said that the name of Moussa, a corruption of Monsieur, was given him by his fellow slaves, in acknowledgment of his dignified deportment and superiority of character … he had been captured by slave-dealers, while tending sheep with his father in the interior of Africa, he was a month on his march to the coast.”

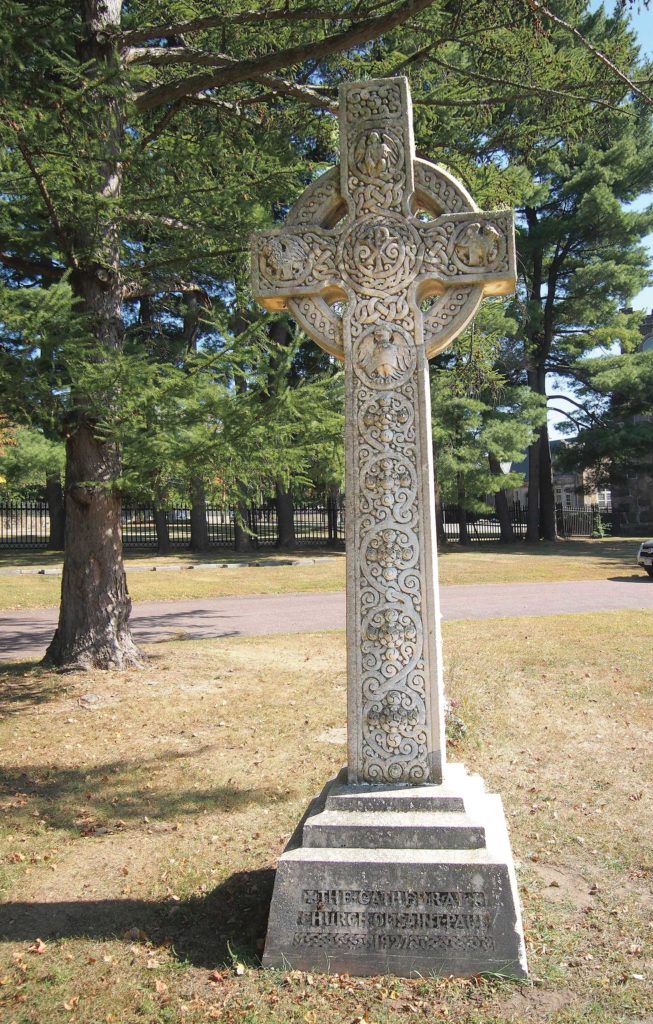

The church in question is the Cathedral Church of St. Paul, an Episcopal church on Tremont Street across from Boston Common. The bodies entombed at St. Paul’s were reinterred in 1914 at Mount Hope Cemetery in Mattapan. The cathedral’s website hosts a spreadsheet culled from original records that confirms Moussa’s re-burial. Although the deceased were afforded their own graves, there are no headstones. Instead, one towering stone Celtic cross marks the lot.

While the list confirms the unusual detail of the family interring the former slave with master James Perkins, it does not shed light on why the family treated his entombment so affectionately. Returning to the genealogy, we learn that when Haiti exploded into full revolt on the night of a dinner engagement, it was Moussa’s actions that “probably saved the lives of the whole party.”

The Haitian Revolution was a successful slave insurrection that birthed the first free Black republic and the first sovereign Caribbean nation. One 1791 evening, James Perkins and his wife Sarah called on their wealthy neighbor the Marquis de Rouvray for dinner; Moussa was alongside. Years earlier, de Rouvray commanded the Chasseurs-Voluntaries, a Black Haitian military unit that fought in the American Revolution at the Siege of Savannah.

During dinner, an eruption of violence swept Cape Francois as the French sugar colony’s Black residents launched their struggle toward self-rule. Plantations were burning and masters were being executed. Word began to pass amongst the enslaved people of de Rouvray’s plantation, and it was Moussa who provided James Perkins with timely intelligence that allowed the white diners to plot a heart-pounding escape to Fort Dauphin.

Two years later, when a siege of Cape Francois became unbearable, brother Samuel Perkins explained, “[w]e had the greatest confidence in our blacks, to whose leader — a faithful slave whom we had long owned (Moussa) — we gave the charge to keep the doors shut and to open them to no one but ourselves … This man had informed us the night before that he had been promised his liberty if he would join the rebels.” It sounds as though Moussa had options, but the Perkins family escaped the house and boarded a Baltimore-bound boat. Minutes later, Perkins witnessed the ransacking of his former home by the Haitian troops.

When did Moussa’s enslavement end?

Modern readers should bristle at any “faithful slave” narrative. I concede that we can’t know what Moussa felt about either the insurrection-turned-revolution in Saint-Domingue or his immigration to Boston. And even if we leave open the possibility that Deyaha felt happy with the arrangement and understood himself as free here, there is no believable option where the Perkins family would’ve admitted that they trafficked Moussa into Massachusetts as a slave and kept him enslaved. Perkins family tradition says that Moussa “refused to be left” in Haiti and he swam out to Samuel Perkins as he boarded the ship, but it’s impossible to know if that’s true.

Deyaha arrived in Boston at a time when slavery was unconstitutional in this state, but no law existed affirming slavery as illegal in the Commonwealth until the 13th Amendment passed. Moussa was born in Africa and lived in a French slave colony; it’s unknown if he spoke English. Subsequently, it’s unlikely Moussa had access to the courts or the language skills to self-liberate; his survival hinged on the mercy of James Perkins’ family. How, then, would Deyaha Moussa’s status differ materially from enslavement? Perhaps the Perkins family papers at the Boston Athenaeum could shed further light on his life.

Something we do know about Moussa’s experience is that the Perkins family obfuscated Deyaha’s narrative. Let’s re-examine the claim that Moussa’s name was “a corruption of Monsieur, was given him by his fellow slaves, in acknowledgment of his dignified deportment and superiority of character.” Since first reading that line, I’ve harbored a festering skepticism.

A Google search validated that skepticism; it revealed that Moussa is an English approximation of the Arabic name for Moses. And browsing Facebook, we find people today with the surname Deyaha in Mauritania, a West African nation where Arabic has been spoken since the 11th century. This realization strengthens Moussa’s ties to Africa and suggests Islamic faith, but I wanted to prove a connection to Islam beyond this circumstantial evidence. After months of searching, I found Deyaha Moussa’s obituary.

The obituary bears the same dishonest language attested to by the Cabot genealogy, but it features a valuable quote announcing that Moussa was “a sincere Mahommedan,” an archaic way of saying that Moussa was a follower of the prophet Muhammad, a Muslim.

Legacies

The legacies of the Perkins brothers shaped today’s Boston — each man played a role in founding the Perkins School for the Blind, and institutions including the Museum of Fine Arts and McLean Hospital were propelled to life with Perkins money. However, these institutions were also shaped by Deyaha Moussa; if he had chosen not to play the role of “faithful slave” and instead had joined his revolutionary Haitian brethren, he could have altered the fate of the Perkins brothers and their gifts. In particular, the Pearl Street mansion in which Moussa lived with James Perkins was bequeathed to and became the former home of the Boston Athenaeum. Notably, Deyaha Moussa doesn’t have a library wing named after him; he is, instead, a Muslim man buried in an anonymous grave adorned with a Celtic cross.

Wayne Tucker is the author of the Eleven Names Project, a blog that uncovers the hidden history of slavery in Massachusetts.