On its first day last Friday, “Paper Stories, Layered Dreams: The Art of Ekua Holmes,” a new show at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), was already full of visitors.

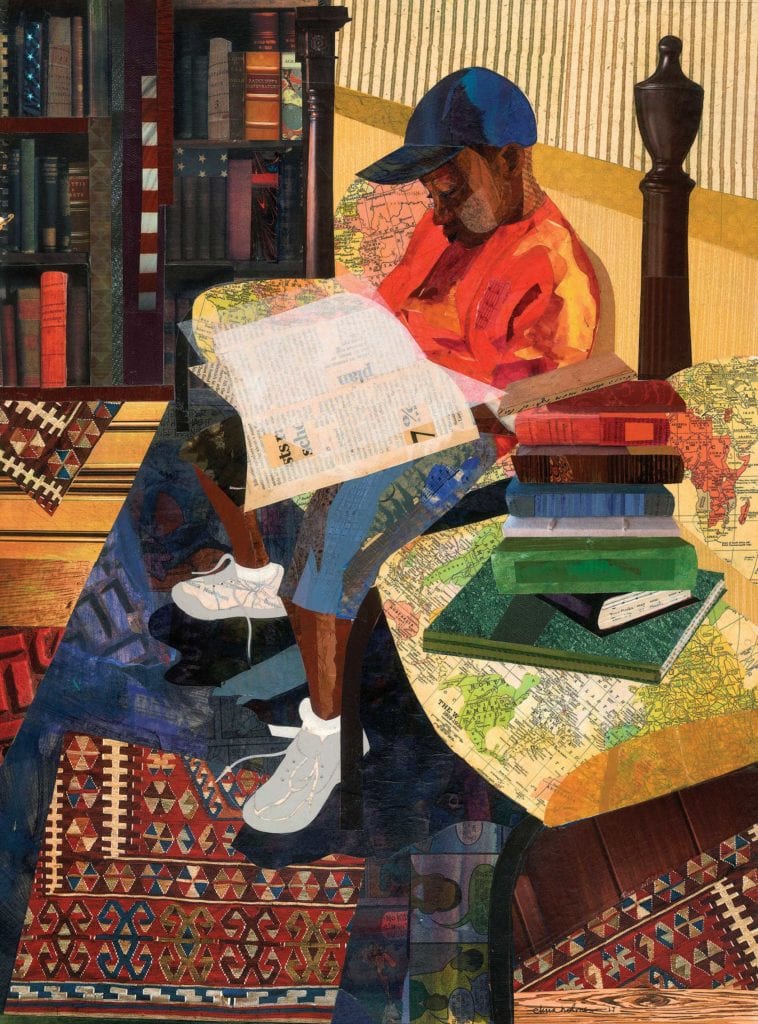

“Golden,” 2009; Collage of found and painted papers; Collection of the artist; © Ekua Holmes COURTESY OF MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON

Organized by Meghan Melvin, the MFA’a curator of design, the exhibition presents about 40 works created over the past decade by Ekua Holmes. On view through January 23, the show features free-standing artworks by Holmes, a lifelong Roxbury resident, as well as her award-winning children’s book illustrations.

Commissioner and vice chair of the Boston Art Commission and associate director of MassArt’s Center for Art and Community Partnerships, Holmes, 66, attended the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts, took studio classes at the MFA and in 1977 received a BFA in Photography from MassArt.

The first of two galleries features studio art produced between 2010-2014 and her first major illustration project, the children’s book “Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement” (2015), by Carole Boston Weatherford. The gallery also shows a five-minute video interview with Holmes.

Installation view of Paper Stories, Layered Dreams: The Art of Ekua Holmes featuring “Idyll of the South: Portrait of Aunt Mary,” 2012. Museum purchase with funds donated by the Board of Trustees in honor of Kevin T. Callaghan, Chair of the Board of Trustees, 2017 – 2020 PHOTO: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

On view in the adjacent gallery are her illustrations from other published books, accompanied by wall texts written by participants in the MFA’s teen curatorial program.

In her illustrations for children’s books, Holmes portrays and celebrates the daily life of Black families in urban and rural settings, rendering scenes in a tropical palette. Her studio art presents closeups of individuals in whom she evokes traces of the history of a family, a neighborhood and a people.

Holmes often employs the bold forms and colors of Expressionism and the flat, abstract shapes of African art. She fashions many images from collages, a technique she has practiced since childhood. Collage suits the layering of times past and the present that deepen her work. Composed from fragments of discarded paper, fabrics, newsprint and books, their translucent layers of color and texture mimic the shimmering layers of memory, refracting and reflecting patterns of light as well as images of events across time.

We know the people in her pictures, whom Holmes renders in their individuality while also evoking the community and era of which they are a part.

“Looking Back,” illustration to

Voice of Freedom, 2014, Collage

of found and painted papers and

fabric. Collection of the artist;

©Ekua Holm COURTESY MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON

In the first gallery, “Looking Back” (2014), from “Voice of Freedom,” portrays a mature woman in a minimalist, sculpted style. Her face exudes enduring strength and her long gaze spans decades.

Nearby are large portraits by Holmes of her grandfather and her aunt, whom as a child she visited every summer in their hometown of Hope, Arkansas. They are part of a series she entitled “Idyll of the South,” a nod to a renowned mural by Aaron Douglas (1899-1979), “Idyll of the Deep South.” Both portraits are framed by wooden shutters, conjuring homes and lives left behind in the Great Migration. Accompanied by a shrine-like installation assembled from keepsakes and evocative curios, each is both an intimate rendering of a figure in a personal family album and a tribute to a shared history of Black Americans.

“Idyll of the South: Root of Jesse” (2012) is a closeup of her grandfather’s weathered, soulful face, its skin fractured in pieces of newsprint as if to reflect headlines and events of years past.

Below the portrait, a bouquet of cotton bolls rests on a large, yellowed Bible open to Isaiah 11:1, “A shoot will come up from the stump of Jesse; from his roots a Branch will bear fruit.”

A small, delicate cameo of her aunt is shown alongside the grand “Portrait of Aunt Mary” (2012), which shows a handsome woman reclining on the grass in front of a barn. Below it, Holmes has placed a vintage sewing table that displays a toy train and envelopes, items evoking the journeys and separations of the Great Migration.