MOORESTOWN, N.J. – Just over the town line from the tree-shaded avenues of this upscale Philadelphia suburb, named not long ago as America’s most livable community, is an inconspicuous triangle of land hemmed in by the Route 73 exit ramp and Camden Avenue.

More than seven decades ago, a tavern once located on this grassy intersection witnessed what many believe was the nascent rumblings of the post-World War II civil rights revolution that brought down the formal structure of American apartheid and moved the nation closer to the redeeming promise of “all men are created equal.”

The 1950 incident at the juncture of the dry Quaker borough of Moorestown and the neighboring blue-collar town of Maple Shade involved a German veteran of the Kaiser’s army in World War I, a Colt .45 army pistol, and a thirsty young theology student by the name of Martin Luther King Jr., who just happened to stop by the nondescript bar on a Sunday outing with friends.

King, a prince of Atlanta’s Black middle class and already an ordained Baptist minister, was a 21-year-old student at the time at Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania. While the Morehouse College graduate and future Nobel laureate lived on the seminary campus, he also rented a room across the Delaware River in the Black community of Camden, New Jersey — a weekend getaway from his studies, a place to seek discreet entertainment outside the moat of the theological ivory tower where he was one of only 11 African American students.

On the morning of June 12, 1950, King and Walter R. McCall, a Crozer classmate, set out in King’s sedan with their dates, Pearl Smith, a Philadelphia police officer, and Doris Wilson, a social worker from the City of Brotherly Love, to take a Sunday spin along the tree-lined roads of South Jersey.

Stopping in at Mary’s Place, a narrow roadside café in Maple Shade, King and his companions, the only Black customers, took a table and waited for service that never came. According to various accounts, King went to the bar and asked for four glasses of beer. The owner, Ernest Nichols, a German immigrant known for serving the best drafts in town, refused, citing blue laws that cut off his taps on the Sabbath.

“No beer, mister. It’s Sunday,” said Nichols, according to a sworn affidavit. King then asked for four glasses of ginger ale.

“The best thing would be for you to leave,” said Nichols, growing irate. King and his friends stayed put — the Garden State’s first recorded sit-in.

According to a police report, the hot-tempered bar owner became verbally abusive when King’s party refused to leave. Nichols then pulled out a semi-automatic Army pistol he kept behind the bar, stepped outside and fired three or four shots in the air.

“I’d kill for less,” the barkeep shouted as he discharged the weapon.

Fearing for their lives, King and his friends fled the premises.

They went to the police, who showed up at the bar and confiscated Nichols’ pistol. The officers didn’t buy Nichols’ story that King was trying to entrap him into an illegal alcohol sale. They arrested and charged the bar owner with disorderly conduct and violation of New Jersey’s two-year-old civil rights law prohibiting refusal of service based on race.

The court case attracted attention in the Black press. Both the Philadelphia Tribune and the Baltimore Afro-American covered it, marking the first time King’s name would appear in the media in connection with civil rights. “Irate Café Owner Routs Tan Customers,” read the Baltimore paper’s headline.

The case was brought before a Burlington County grand jury but was dismissed when several witnesses refused to testify.

Though the court complaint went nowhere, the incident loomed large in King’s life. Years later, in remarks to reporters as well as in U.S. Senate testimony, the civil rights leader cited the confrontation as a formative step in his commitment to a more just society.

“They refused to serve us,” King told a Tribune reporter during a 1961 interview before delivering a speech on integration at the Philadelphia Academy of Music. “It was a painful experience because we decided to sit in.”

King graduated from Crozer in 1951 at the top of his class, despite earning a lowly C in public speaking, and went on to earn a Ph.D. from Boston University before taking up the pulpit in Montgomery, Alabama, that would lead to his fame as a leader of the bus boycott started by seamstress Rosa Parks.

The Walnut Street row house in Camden, N.J., where the young Martin Luther King Jr., rented a room. PHOTO: ERINT IMAGES

The gifted orator who held the nation spellbound with his “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington became a global leader for peace and justice when he came out against the Vietnam War in 1967 — a year to the day before his assassination in Memphis where he was rallying with striking sanitation workers.

Meanwhile, Mary’s Place changed hands as Nichols moved a few years after the incident from Maple Shade to Riverside, New Jersey, where he opened Ernie’s Tavern. The pub underwent several name changes, including the Jade Tavern, before ending as the Moorestown Pub before it was torn down in 2011 to make way for upgrades to the Route 73 cloverleaf.

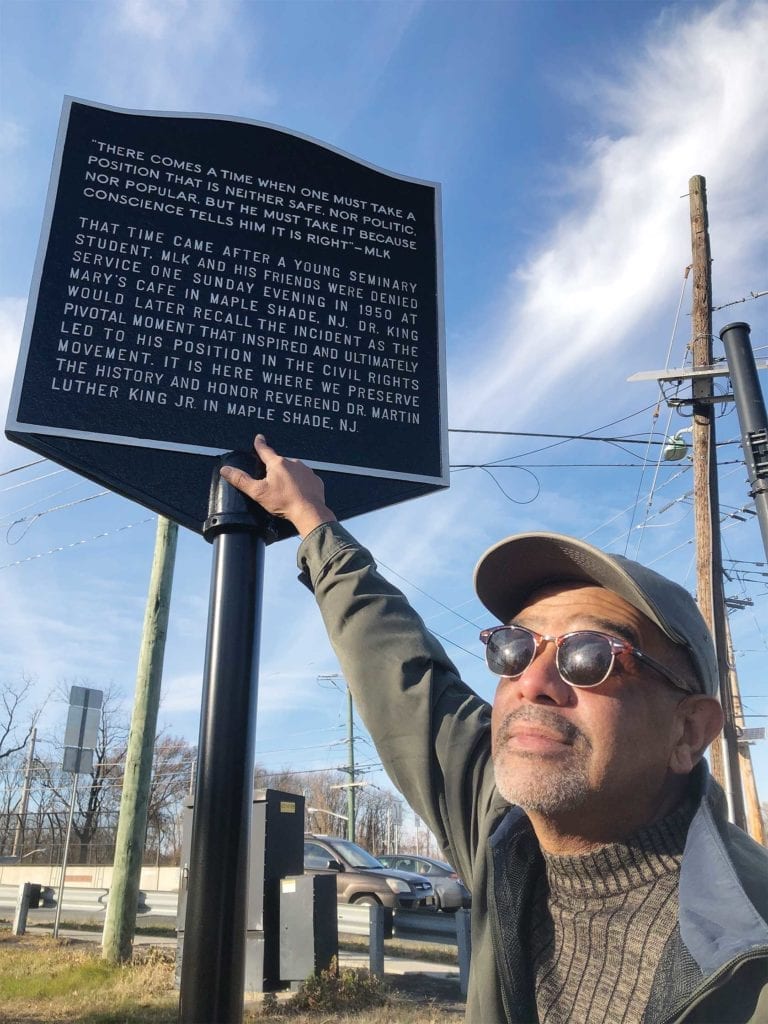

In Moorestown’s Black community, one of the oldest in South Jersey, there was some awareness of King’s confrontation with intolerance at the edge of town, but it wasn’t until recently that local officials, historians and activists gathered to commemorate the incident with the placing of a marker at the site.

“It was something that we knew about, but it was little more than rumors,” said Rodger Berry, 66, who grew up in Moorestown, the son of a pioneering RCA engineer. “Every now and then, when it was the Jade Tavern, the bartender used to talk about it and said there were bullet holes in the ceiling and on the wall.”

The pub, a popular meeting site for some and the closest place for residents of dry Moorestown to buy beer to go, never fully lost its slightly menacing aura to African Americans wary of patronizing a bar mostly frequented by a tough white working-class clientele.

It was not a place, said Berry, where he and his friends spent a lot of time.

Pat Duff, a realtor and civil rights activist in nearby Haddon Heights, uncovered the King connection to the site while doing research on Maple Shade and convinced town officials to erect a marker there, with the cost covered by the borough and private donors.

The marker, set amidst patchy grass and small trees struggling to thrive amid the exhaust fumes, is easy to miss.

The Camden rowhouse on Walnut Street, which King gave as his address to police, sits in the same neighborhood where Berry’s family lived before his father, one of the first Black engineers hired by RCA, moved to Moorestown to work at the defense contractor’s expansive new facility in the suburbs.

The Walnut Street home, forlorn and dilapidated, has been the target of desultory efforts by local activists and historians to refurbish as a monument to King.

At least the marker at the tavern site serves as reminder of what transpired there, said Berry.

“I slow down to look at it every time I drive by,” he said. “It’s history.”