The city of Boston’s initiatives to increase income-restricted housing have provided affordable spots, especially important during a time where job loss can mean missing rent payments and subsequent eviction. But displacement still persists, and the city is working to keep struggling residents in their homes.

To examine how dire the situation is, anti-eviction advocates at City Life/Vida Urbana partnered with MIT to produce a study on eviction during the pandemic and found that, though eviction moratoriums were in place at the federal and local level, evictions still occurred the most in communities of color.

Even though only 40% of all rental housing, not just income-restricted housing, is located in Roxbury, Dorchester, Mattapan and Hyde Park, 64% of all eviction filings occurred in these neighborhoods during the height of the pandemic.

“Boston’s communities of color need and deserve stable housing in the pandemic. But 7 out of 10 eviction filings in the first year of COVID-19 were in parts of town where most renters are people of color, even though less than half of our city’s apartments are in these areas,” said Mike Leyba, City Life/Vida Urbana’s director of development in a statement.

Rising rents and joblessness have led to evictions, especially since those eviction moratoriums expired. Landlords across Massachusetts have filed over 10,000 no-fault and non-payment evictions since the end of the moratoriums. These kinds of evictions happen often because of a recent job loss or rent hike. Subsequent protests against eviction have erupted among tenants in East Boston, Jamaica Plain, and Hyde Park from January to April.

“That’s why we’re calling on our state Legislature to immediately intervene — they should pass the COVID-19 housing equity bill before more families of color are dangerously and needlessly evicted,” Leyba said.

The Act to Guarantee Housing Stability During the COVID-19 Emergency and Recovery, which Leyba is referring to, has been stalled in the Legislature since January.

The city has made attempts to meet demands for more affordable housing. Boston’s Department of Neighborhood Development has reported increases in income-restricted housing, typically referred to as “affordable housing,” over the last year. According to the DND’s most recent report, released April 6, 20% of all rental units in Boston are income-restricted.

The rental units are priced at intervals for families and individuals making a certain percentage of the area’s median income (AMI). The percentage of income-restricted housing is higher in some areas than others, such as Roxbury, where 55% of the total housing is income-restricted or “affordable.”

But what makes a rental unit affordable? The DND’s report, which covers the overall affordability of Boston, details what levels of income the BPDA uses to determine how much a unit will cost.

A single person making 50% of the AMI is estimated to make a maximum of $44,800 and to be able to afford a one-bedroom unit at a maximum $1,200 per month.

A family of four at 80% AMI makes a maximum of $95,200 and pays a maximum of $2,661 for a three-bedroom unit, according to the tables.

In these examples, the maximum “affordable” rent is slightly more than 30% of gross income. Whether this is affordable enough depends on each individual or family situation, including other expenses they may have, like debt or medical bills.

Roxbury has the highest percentage of affordable housing in the city, in rental and homeownership units. Chinatown has the second highest percentage affordable, at 49%. These numbers are mostly made up of rental units — home ownership units are scarce, and only a small percentage of them are designated affordable.

For instance, 38% of the units in Mattapan are homeownership units, and only 1% of those units are income-restricted.

Helping those seeking affordable homeownership is Symone Crawford, director of homeownership education at the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance.

“During the realtor conversation, you can hear that there are no homes out there,” Crawford told the Banner. “The need is much greater than what is available out there, the demand is much higher. Which is why MAHA has been trying our best for almost all of our existence to advocate for more affordable homeownership opportunities.”

Crawford works with first time homebuyers to get them prepared to purchase but finds the lack of income-restricted homes to be a problem, especially for people of color, who generally have lower incomes and less family wealth than whites.

“Whites have double the homeownership rate as opposed to Blacks,” Crawford said.

She adds that intrinsic bias can widen the gap as well.

“As we know, systematically, people have been disenfranchised and erased from entering into the homeownership market,” she said. And when an affordable home goes up for sale, she noted, there are thousands of applicants, weakening their chances.

On the rental side, the Boston DND reports 1,023 new units of affordable rental housing were created in 2020. The Boston Planning and Development Association has had success with programs like PLAN: Nubian Square in engaging the community and setting restrictions that require two-thirds of housing developed on city-owned land be income-restricted. Public parcels, including Parcel 8 in Roxbury, which was recently designated to a developer, will add new affordable units through the next five to 10 years as developers continue to make their bids for the land.

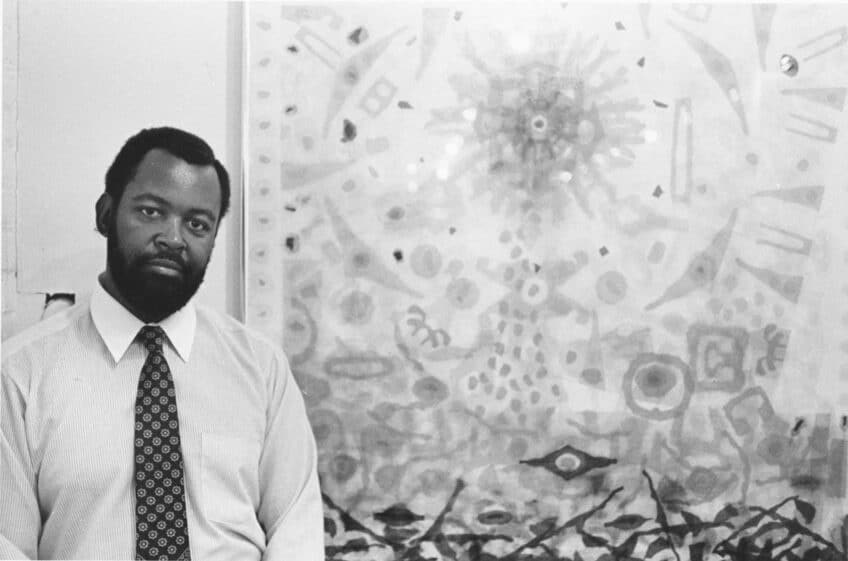

Armani White, an organizer with Reclaim Roxbury, is on the project review committee for a few upcoming developments that promise to secure more housing for Boston’s most affordable neighborhood through the PLAN: Nubian Square process.

“We’re proud to have standards that require developers to build a third [of units] low-income, a third middle-income, and a third market-rate,” White said.

“There’s an attempt to create more affordable housing, either through homeownership opportunities, through affordable housing rental opportunities, or through using public land for public good,” he continued. “There needs to be more than that.”

Some steps have been taken at the statewide level: an eviction-sealing act that would stop no-fault evictions from following people forever; a provision giving tenants the right of first refusal when their building goes up for sale, and a law that makes it easier for Boston to change its zoning code and increase development.

While Governor Baker signed the zoning code law, he vetoed a section that would require more affordability. He also vetoed the other two provisions that would directly benefit Boston’s affordable housing renters.

White says that though more affordable housing is being built, there are still many barriers to accessing it. Recently, an abutter brought a lawsuit against a proposed Jamaica Plain development dedicated to providing housing for people experiencing homelessness.

“There’s definitely steps being taken, but it’s not enough,” he said.