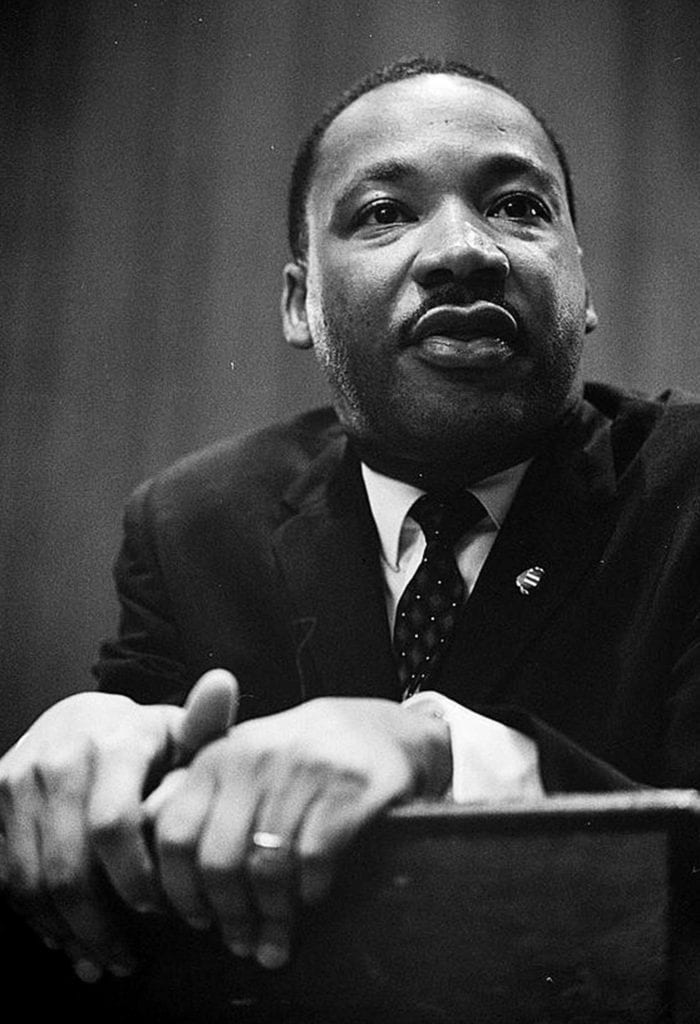

The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., the son and grandson of Baptist ministers, was born not just to preach, but to preach to the world.

His father, Rev. Martin Luther King Sr., was a sharecropper’s son who worked his way through Morehouse College. King Sr. became pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia in 1931, where his father-in-law, Rev. A.D. Williams had served as the pastor before him.

1929 –1953

The King family shared a home at 501 Auburn Avenue in Atlanta with the Williams household. King Jr. was born in that house on January 15, 1929.

His mother, Alberta Williams King, was a former public elementary school teacher and an accomplished musician who was forced by Atlanta Board of Education rules to give up her teaching post after she married King Sr.

Young Martin Luther King Jr. grew up with an older sister, Christine, and a younger brother, Alfred Daniel, who was called “A.D.” Martin was known as “M.L.” among family members.

At the age of six, King entered Atlanta’s segregated public school system at the David T. Howard Elementary School. He left the public schools for several years to join his sister at the Atlanta University Laboratory School, a private experimental school run by the university.

He spent two years at the Lab School before skipping the ninth grade to enter Atlanta’s oldest Black public secondary school, the Booker T. Washington High School.

By all reports a bright and inquisitive student who reflected his family’s interest in learning, King Jr. also possessed a rambunctious spirit. He liked to dress well and dance — indulgences that never held back his academic progress, for he flew through his studies at Booker T. Washington and was accepted at Morehouse College at the age of 15.

According to King Jr.’s sister, Christine King Farris, the summer before he entered Morehouse College would prove extremely influential in his development. He traveled north in 1944 to Simsbury, Connecticut to work on a Connecticut tobacco farm. Away from the oppressive conditions of Jim Crow laws violently enforced in the South, King Jr. was struck by the relative freedom Blacks enjoyed in the North.

At Morehouse College, King Jr. came under the influence of Dr. Benjamin E. Mays, the Morehouse president who was a mentor to several generations of students. Dr. Mays’ devotion to social justice helped dispel any hesitation King Jr. may have had about a career in the ministry.

Corretta Scott King and Martin Luther King, Jr. at Boston University. The university houses King’s archives.

He became an ordained Baptist minister before the end of his senior year at Morehouse, from which he graduated in 1948, at the age of 19, with a B.A. degree in sociology.

King entered Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, in September 1948. There, inspired by a speech by the pacifist A.J. Muste and the writings of Rheinhold Niebuhr, he began to study the life and teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, whose advocacy of nonviolent demonstrations to achieve social change helped shaped the course of the future Nobel laureate’s life.

One of only six Black students at Crozer, King received a bachelor of divinity degree in 1951, graduating with top scholastic honors. He was also president of his senior class, most outstanding students and the recipient of a graduate fellowship award.

King decided to use the Crozer Fellowship award to pursue doctoral studies at Boston University. While studying in Boston, he was introduced to Coretta Scott, a voice student at the New England Conservatory of Music who sang in the Twelfth Baptist Church choir where King was a guest preacher. They were married in 1953 in her Alabama hometown, in a ceremony officiated by his father.

During their 15 years of marriage, the Kings had four children: Yolanda Denise, Martin Luther III, Dexter Scott and Bernice Albertine.

1954 – 1957

With just his dissertation to finish for his Boston University Ph.D., King went south to become the 20th minister of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. King’s new assignment put him squarely in the arena of civil rights advances for Blacks bolstered by the May 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision outlawing racial segregation in the public schools.

His first year as full-time pastor of the Dexter Church was a momentous one: it saw the birth of his first child Yolanda, the awarding of his Ph.D. in systematic theology from Boston University, and the opening of the Montgomery bus boycott, which thrust King, 26, into the limelight of the southern civil rights struggle.

King, photographed with the late John Lewis (left) during the March on Washington. PHOTO: NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION

The boycott was prompted by the actions of Mrs. Rosa Parks, a Black seamstress, who, on December 1, 1955, refused to give up her seat to a white man and move further back on a city bus.

Rosa Parks’ subsequent arrest prompted a boycott by the Montgomery Improvement Association and King, who was elected its president, as well as other community leaders.

National and international attention focused on Montgomery during the boycott so inflamed those opposed to integration, that King and his family were the targets of numerous death threats.

On January 26, 1955, King was arrested and spent a night in jail for driving 30 mph in a 25 mph zone. He was released the next morning on his own recognizance. Three days later, while King was out of town addressing a mass meeting, a bomb was thrown on the porch of his home. His wife and child escaped with only minor injuries.

Dr. King drew on his deeply held belief in nonviolence to calm the angry vengeance-seeking crowds that gathered at his home after the bombing.

In February 1956, King was indicted along with other boycott organizers on charges of unlawfully conspiring to obstruct the “just” operation of business. The charges came after the filing of a federal district court suit to have Montgomery’s segregation of public transportation declared unconstitutional.

In June, a U.S. District Court agreed with the plaintiff – a decision upheld in November by the Supreme Court. In December 1956, little more than a year after Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat, the Montgomery buses were integrated for the first time.

Riding the momentum of the bus boycott victory, King helped to organize the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in January 1957. He was elected its first president, prompting Time magazine to run a cover story on King.

The same month King was elected SCLC president, an unexploded bomb was removed from the front porch of his home.

Events in 1957 accelerated the attack on legal barriers to segregation. King, in numerous public appearances, hammered away at Jim Crow, quickening the pace of reform all across the South. His May 17, 1957 “Give Us the Ballot” speech — the culmination of the Prayer Pilgrimage March on Washington — was a hallmark call for the extension of voting rights to all citizens.

The speech, delivered on the third anniversary of the Supreme Court’s desegregation decision, helped rally support for the passage of legislation protecting the voting rights of previously disenfranchised citizens eligible to cast their ballot.

King’s growing status as an international leader in the crusade for equality was credited for helping to achieve other civil rights victories. International scrutiny, drawn by the charismatic Georgia-born preacher, increasingly turned its gaze on injustice in America.

In September 1957, President Dwight David Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard to escort nine Black students into previously all-white Central High School in Little Rock. That same year, Congress passed the first civil rights act since the Reconstruction era, creating the U.S. Civil Rights Commission along with the Civil Rights Division within the U.S. Justice Department.

1958 – 1961

The year 1957 saw the publication of King’s first book. “Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story.” The book was published the same month King was arrested for loitering near the Montgomery Recorder’s Court. He was released on $100 bond and later convicted. His fine was paid against his will by the Montgomery Police Commissioner.

Despite King’s message of nonviolence, he continued to be the target of violent attacks. While attending a September 1957 book-signing ceremony in Harlem, he was stabbed by Izola Curry, a Black woman later said to be mentally disturbed.

Pursuing his interest in Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of social change, King and his wife left the United States in February 1957 for a month-long visit to India, where they were the guests of India Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

In King, the spiritual heir to Henry David Thoreau and his American brand to civil disobedience, the world was beginning to recognize a man who could combine the nonviolent traditions of East and West to create a force for change that would see most of the legal barriers to integration broken down within his lifetime.

After King’s return to Alabama, he spent only eight more months at the helm of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. In late November 1957, he resigned his position to become co-pastor, with his father, of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta.

The new decade of the 1960s introduced a new spirit to activism, but also saw law enforcement authorities, guided by anti-King forces, trying to curb King’s influence through a series of legal salvos against the civil rights leader.

The opening shot came with trumped-up perjury charges connected to his 1956 and 1958 state income tax returns. Three months after the charges were filed against him, an all-white Montgomery jury acquitted King of the accusations against him.

Turning aside false charges, however, did not stop King from inviting arrest for deliberate violations of law in the name of justice. On October 19, 1960 he was arrested along with 51 others at an Atlanta sit-in held to protest segregation of public facilities. All of those arrested were released except King, who was held for violating probation given in an earlier traffic case. King was transferred to Reidsville State prison, from which he was released five days later on a $2,000 appeal bond.

King’s widely publicized skirmishes with the law served to fuel numerous sit-ins, marches, prayer vigils and demonstrations against racial oppression, many of which he led.

King barely had time to attend the birth of his third child, Dexter Scott, in January 1961, before a major wave of Freedom Riders began spreading across the South. Organized by the Congress of Racial Equality, the Freedom Riders planned rolling demonstrations against segregation of transportation facilities from Virginia to Mississippi.

Bomb-tossing racists in Alabama disrupted the Riders’ May 1961 journey, prompting CORE to scuttle the bus-borne pilgrimage of hope. But a new group of student riders set out from Nashville for Montgomery, where they took refuge from a hostile mob inside a church. King and other leaders spent an all-night vigil with the group, which was freed in the morning by 400 federal marshals sent by U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

The Montgomery confrontation led to a summer-long resumption of the Freedom Rides, with hundreds going to prison over their role in public demonstrations. The Rides eventually resulted in the Interstate Commerce Commission providing guarantees that regulations against unlawful segregation would be carried out. 1962-1964

In late 1961, King began his participation in demonstrations against segregation in public facilities in Birmingham, Alabama. Arrested during an April 1963 sit-in, King wrote the historic “Latter” from a Birmingham Jail, a moving defense of his reasons for deliberately breaking the law in the name of justice.

On Aug. 28, 1963, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” in Washington, D.C.

King sat in prison while at home his wife was looking over their fourth child, Bernice Albertina, born one week before the opening of the Birmingham demonstrations.

Among the numerous mobilizations against segregation organized by King in Birmingham, his May 1963 “Children’s Crusade” was considered the most effective. Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor horrified the world when he ordered police to use attack dogs and fire hoses on thousands of young children organized by King to march against injustice.

By the end of the month, the U.S. Supreme Court had struck down Birmingham’s segregation ordinances as unconstitutional. In the months following Birmingham, demonstrations in other cities and towns in the South led to similar victories for the forces of integration. The hard-fought victories of the spring and summer of 1963 led up to the greatest mass civil rights demonstration ever held — the August 1963 March on Washington, which culminated in King’s famous “I Have A Dream” speech delivered on August 28, 1963 from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

More than a quarter of a million people, of every race and color, nationality and creed, participated in the gathering, a milestone in the struggle for equal rights.

That high-water mark was marred, however, less than three weeks later by the bombing murder of four Black children at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. Striving to spread his message of nonviolence and love in a climate of escalating hatred, King published two books within a single year – “Strength to Love,” appearing in June 1963, and “Why We Can’t Wait,” released in June 1964.

But his advocacy of peaceful change through meaningful reform went unheeded by many, as the summer of 1964 saw riots explode in the urban centers of New York, Chicago, Newark and Philadelphia.

Legislative gains for Blacks passed during this period included the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, measures that for increasingly militant members of the Black community offered too little too late.

In September 1964, King again traveled abroad as an unofficial ambassador of world peace. He was received by Willy Brandt, the West German head of state, and met with Pope Paul VI at the Vatican. The highlight of his odyssey, though, was his acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize at ceremonies held in Oslo, Norway. He received the award graciously, with a speech declaring his “abiding faith in America and audacious faith in the future of mankind.”

1965 – 1968

But the America to which King returned was not entirely prepared to demonstrate the faith he possessed. Demonstrations in 1965, though largely successful in bringing pressure against the legacy of Jim Crow, were often marred by violence.

The highlight of King-led civil rights actions that year was the Freedom March from Selma to Montgomery, in which 3,000 people setting out for the Alabama capital were joined by 250,000 others along the way, King addressed the marchers, protected by federal troops, on the steps of the Capital at the end of their journey.

Protests against racial injustice were not limited to the South in that era. King traveled north on several occasions to lend support to integration movements in cities where de facto segregation existed. He came to Boston both in 1964 and 1965 to help lead protests against racial imbalances in the city’s public schools.

During the April 1965 visit, he led a march from the Carter Playground on Columbus Avenue to the Boston Common. He also addressed a joint session of the state Legislature, which had been resisting passage of the Racial Imbalance Law to make de facto segregation illegal.

The House of Representatives chamber was packed for the King address, in which he bowed to the memory of John F. Kennedy before launching into the heart of his text — an attack on the practice of segregation. Without mentioning Boston or Massachusetts specifically, it was clear his references to segregation were directed at the state of the Boston school system.

Other cities outside of the South visited by King as he sought to expand the scope of civil rights activism included Chicago, where he opened up a campaign in 1966 to end segregated housing in the city.

That same year also saw King taking his first public stances against the Vietnam War. He denounced the war at a May 1966 rally held in Washington, D.C. His statements there immediately generated a firestorm of controversy, dividing those who applauded his views and those who believed his foreign policy position would compromise gains for Blacks in the domestic arena.

A memorial to King and his “I have a dream” speech was in 2003 etched in the granite steps of the Lincoln Memorial where he delivered the address. ADOBE STOCK

Despite accusations of communist sympathies and anti-American attitudes, King continued to speak out against the war, drawing the wrath of powerful enemies such as FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.

The hostilities abroad that King denounced were echoed in 1966 by hostilities at home. The murder of civil rights activist James Meredith cut short his “March Against Fear” from Memphis to Mississippi. King and others completed the 220-mile journey while calling for peace, but an escalating cycle of violence was gripping the nation.

In August 1966, King was stoned by a group of whites in Chicago who were angered by his demands for integration in the city. King opened the year 1967 on a noted of urgency, publishing “Where Do We Go From Here?” amidst calls for armed rebellion by Black militants.

To the cries of “Burn, baby, burn!” King counseled a program of economic inclusion to blunt violent reactions among the downtrodden. “Earn, baby, earn!” said King to audiences. But violence was gaining ascendancy. The summer of 1967 saw riots in Black communities around the country. The disturbances were likened to open rebellion in cities such as Detroit, where scores were killed as tanks rolled the streets and thousands were left homeless by fires scorching the inner city.

King launched the SCLC Poor People’s Campaign in November 1967 to address the needs of the impoverished, whose urge to riot, said King, was “the language of the unheard.”

Pressing his policy of economic reform, King voiced his support in 1968 for striking sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee. He led 6,000 marchers through the city’s downtown area on March 28, 1968 in support of the workers.

The march turned ugly, however, leaving one teenager dead and many others injured. The Memphis demonstration saw King deliver his last speech, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” at the Memphis Masonic Temple.

Eerily prophetic of his impending death, King told his audience one day before his assassination, “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will, and He has allowed me to go up the mountain, and I’ve looked over and I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the promised land.”

“So I am happy tonight. I am not worried about anything. I am not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

The next day, on April 4,1968, as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down by a sniper. He was 39.