Parks Service compiling online database of 54th Regiment soldiers, officers

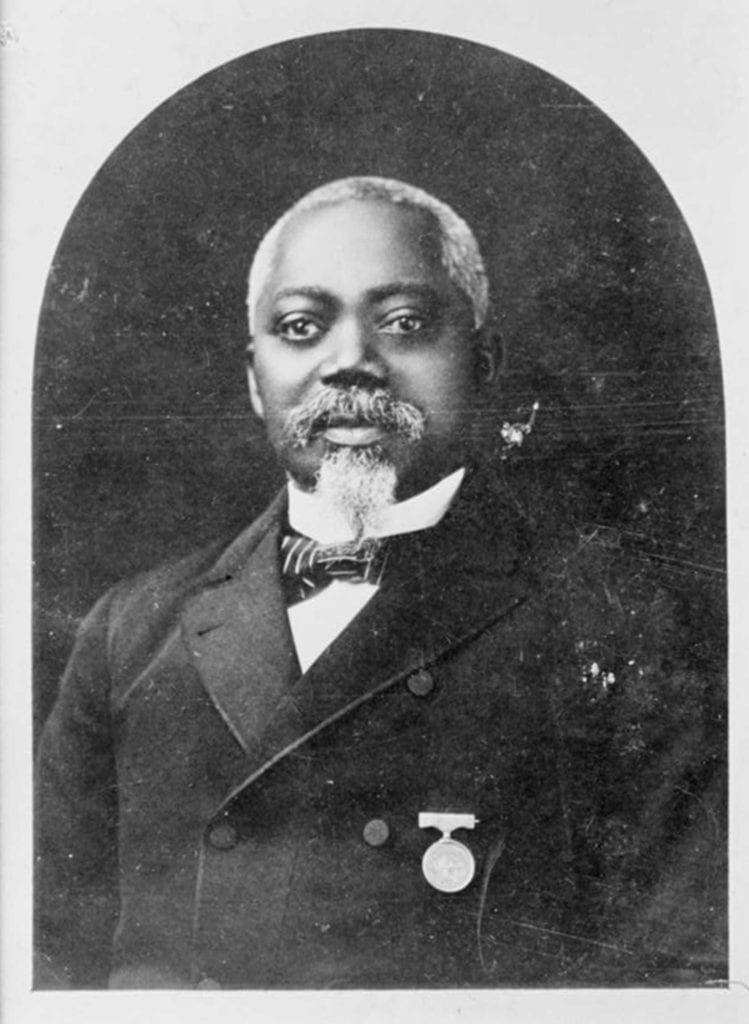

Civil War Sergeant William Carney’s path to freedom wasn’t entirely uncommon among Black Bostonians in the late 1800s: Born into slavery in Norfolk, Virginia in 1840. He learned to read in secret, in defiance of Virginia law. Freed or escaped (no one knows for sure), he and other family members settled in New Bedford before making their way to Boston.

Although Carney felt called to a life in the ministry, the outbreak of the Civil War and the call to arms by the all-Black Massachusetts 54th Regiment changed the course of his life.

“I had a strong inclination to prepare, myself for the ministry; but when the country called for all persons, I could best serve my God by serving my country and my oppressed brothers. The sequel is short — I enlisted for the war,” wrote Carney, as printed in The Liberator, the weekly abolitionist newspaper printed by Roxbury resident William Lloyd Garrison.

Carney played a pivotal role in the regiment’s siege on Fort Wagner, retrieving the American flag after its bearer was shot down and planting the flag on the fort’s parapet, all the while pressing his own wounds to stanch the bleeding. When the regiment was forced to retreat, he carried the flag back to Union lines, never letting it touch the ground. For his valor, he became one of the first African Americans given a Congressional Medal of Honor.

This bas relief monument to the Massachusetts 54th Regiment is currently undergoing renovations. PHOTO: COURTESY FRIENDS OF THE PUBLIC GARDEN

Carney’s story is among the many being collected by the Boston African American National Historic Site, a local arm of the National Park Service, as part of its “Faces of the 54th” soldier and officer database.

The effort has collected the names and details of over 1,500 men who served with the volunteer 54th Massachusetts Regiment between 1863 and 1865, when the Civil War ended. Data listed include the men’s age, enlistment and mustered-out dates, place of enlistment, profession at enlistment, rank and company.

Sherry Guillen, a park guide with National Parks of Boston, said she and other rangers began working on the database over the summer, combining entries from existing online rosters of enlistment to compile a list for the 54th Regiment.

The project was inspired by a community member who asked what the National Park Service is doing to tell the stories of the men who served in the all-Black regiment.

“I thought it would be great to expand those stories,” Guillen said.

Besides the database entries, the project features a few deeper stories of the men behind the data.

So far, website visitors can see the stories of Carney; Isaac S. Hawkins, who was captured by Confederate troops; and Captain Luis Emilio, a Spaniard who after the war wrote the first history of the 54th Regiment, published in 1891.

Guillen hopes to add more stories to the website as they emerge.

Historian Kevin Levin, who has authored several books on the Civil War, said the proliferation of online databases has helped make the history of the conflict more accessible. Several decades ago, many Americans viewed the Civil War through a different lens.

“The popular story of the war was really a narrative of reconciliation,” he said. “The brave white men on both sides of the war who fought valiantly.”

When the film “Glory” came out in 1989, it challenged commonly held beliefs that Blacks played no role in the conflict.

“People were confused as to whether it was fact or fiction,” he said.

The National Park Service database illustrates how much more visible Black soldiers have become and how much more accessible their stories are. Black and white abolitionists in Boston began recruiting soldiers in 1863, after President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation cleared the way for Blacks to fight in the U.S. Army.

The men who enlisted in the 54th worked as farmers, laborers, barbers, servants and seamen. Recruiters from Massachusetts enlisted them in towns such as Bristol, Vermont, Catskill, New York, Taunton and Medfield in Massachusetts, and New York City.

Levin says such details help paint a fuller picture of the men who fought for the freedom of their brothers and sisters in the slave-holding states.

“Their backgrounds tell you a lot about the profile of this regiment,” he said.

For many people whose families have passed down stories of ancestors who fought in the Civil War, the database could add critical details to their family lore.

“I can imagine that for some people, seeing an ancestor’s name in a database maintained by the National Park Service is a validation,” he said. “It’s a feeling that you belong.”