A new political reality

Despite patriotic exhortations to the contrary, there never seems to have been unbridled enthusiasm for universal plebiscite in America. The Founding Fathers denied the vote to women and to slaves. In fact, very few whites were welcome at the polls on Election Day — just men with substantial property holdings.

Those in power began to realize that it was necessary to expand the franchise in order to live up to the nation’s democratic principles. In 1870, the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted the right to vote to blacks and to former slaves, and in 1920, women got the right to vote.

However, a constitutional amendment was not enough to ensure those rights to African Americans. The imposition of the poll tax and rigorous, nonsensical registration requirements kept blacks away from the polls. When these strategies did not work, there was little reluctance to resort to violence.

Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965 to assure that the states of the Confederacy did not employ disenfranchising practices that seemed to be legitimate but were merely stratagems to discourage black voters. It was apparent in the recent presidential election that voter ID laws in some states were designed for that purpose.

It is no wonder, then, that the race or ethnicity of voters is of great importance in politics. And while the women’s right to vote cannot be circumvented, gender is still an issue in the selection of candidates for high office.

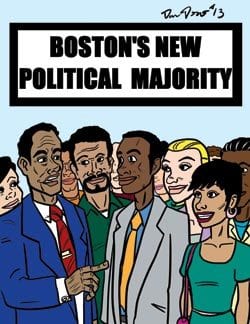

In Boston, the majority population is no longer white. Blacks, Hispanics, Asians and other non-whites constitute 53 percent of the population of 617,594. According to the 1910 Census, there were 13,569 black residents, only 2 percent of the city’s population. In the intervening years before the demographics first shifted, blacks could not participate in Boston politics as a power bloc that had to be recognized.

The significance of this population shift is not generally understood. It does not mean that so-called minorities will now vote only for one another. That certainly was not the case with the recent election of Sen. Elizabeth Warren. It is also clear that they will show up on Election Day if there is no black candidate.

However, the demographic change does mean that black, Hispanic or Asian citizens will be more willing to step forward as political candidates because the bigotry of some voters will now be insufficient to assure their defeat. Already 11 such citizens have expressed an interest in becoming mayor after Tom Menino leaves office.

Perhaps the most important aspect of this demographic shift is that no political candidate can hope to win an election in Boston if his or her campaign supports any form of racial discrimination. This political reality will help create a spirit of racial congeniality that should embrace the whole city.

It took many generations for Boston’s black community to become large enough to be politically significant. In the decades ahead, citizens will undoubtedly coalesce more around shared political values rather than tribal solidarity. Boston will then become a truly cosmopolitan city.

Boston’s demographic shift is indeed its most significant political event. Old ethnic neighborhoods will be altered. The city’s real test is how well its citizens adjust to the changes and remain “Boston Strong.”