(AP Photos)

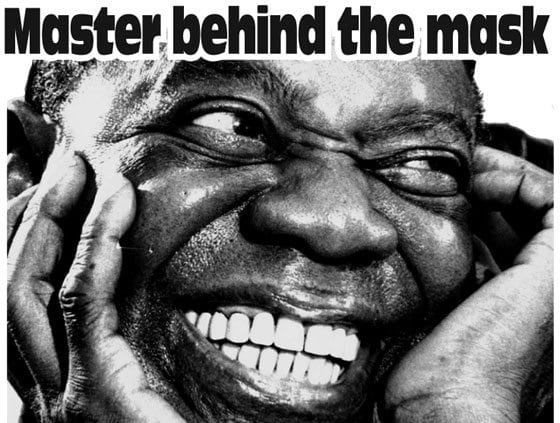

New Armstrong bio looks underneath the grin of a great musician

Louis Armstrong did more to popularize homegrown American music than any performer before or since. With the biography “Pops,” “Wall Street Journal” drama critic Terry Teachout is the first trained musician (he writes opera and played jazz bass) to write a fully sourced biography of Armstrong.

The author admittedly drew not only from a wealth of recently available scholarship about “Satchmo,” but private letters and previously unpublished photographs, notes and manuscripts, and 650 of the entertainer’s reel-to-reel tapes featuring jokes, radio interviews, recorded gigs, classical music, ruminations and casual conversations. Teachout skillfully integrates the private Pops with previous research to develop his portrait.

Armstrong saw himself as a figure that grew up simultaneously with America’s impressionist music, giving his date of birth as July 4, 1900 (he likely did not know it was August 4, 1901). He took to music early in his native New Orleans, playing in the band of a colored waif’s home, and sneaking looks inside the seedy dives of the notorious Storyville district.

Young Louis was close to his mother and sister, though he was aware his mother not only cavorted with an endless string of “uncles,” but may have turned the occasional trick. He spoke very little of his father who abandoned the household when he was very young, and throughout his life had no sympathy for irresponsible black males — a sore spot repeated in his personal journals. By 15 years old, he adopted his young cousin Clarence, who became developmentally disabled after a bad fall.

When he was a steamboat band member, the teenaged Armstrong’s singular tone caused fellow musicians to take notice. At 21, he was called to join Joe “King” Oliver’s band in Chicago. There he became the most talked about cornet (and eventually, trumpet) player in the genre that was taking Prohibition America by storm. His piano playing band mate and wife Lil Hardin encouraged him to think bigger than father figure Oliver and strike out on his own.

Pops’ combination of virtuosity and showmanship made him a rising star, if a controversial one. He learned lessons of simplicity and melody from Oliver — such that he became a fan of bandleader Guy Lombardo, whom most contemporary players and critics deemed pedestrian at best. Armstrong was the first cornet and trumpet player able to convey great emotion in the upper register of his instruments. His scat singing, delivered in an instantly recognizable gravel tone, boosted his appeal live and on wax. Fellow musicians, Bing Crosby included, felt Armstrong “never really had a very good band.” Producer-critic John Hammond, who helped launch the careers of Billie Holliday, Benny Goodman and Bob Dylan, saw Pops as a stellar player burdened by second-rate bands.

Teachout disagrees. The author argues that the large bands in which Luis Russell was Pops’ musical director were talented, but Armstrong entrusted arrangements to men incapable of developing a signature style suited to his unique gifts. By contrast, the bands of Goodman, Count Basie, and Duke Ellington had a “sound.”

Enigmatic souls make compelling biographical subjects. The enduring paradox about Armstrong was what the author calls his “virtuoso clown” existence, the joyful stage presence many critics had difficulty reconciling with “fertile improviser” status. Teachout measures the exaggerated facial gestures, hipster ad-libs and minstrel lyrics in the context of the era, buffeted with his subject’s deeper thoughts. Among Armstrong’s own writings are musings on women, business, the virtues of marijuana and accountability in the black community.

When his still largely unknown band was playing one-nighters in the predominantly white Midwest, Armstrong developed what younger trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis would later call “clown antics.” For his part, Armstrong also felt obligated to impress those audiences with “demonstrations of his superhuman powers,” such as his ability to play 250 high notes in succession. He worked his band mates hard, 300 nights a year like their early 1930’s contemporaries, the equally criticized Harlem Globetrotters (who began as a Chicago team called the Savoy Ballroom Big Five). Pops’ famed Hot Five recorded as “Louis Armstrong and his Savoy Ballroom Five.”

Armstrong was a bit of an oddity. Even as a young star, Pops handed out money and gifts to lines of admirers outside his hotel rooms. He refused to play in his hometown New Orleans for years because it forbade integrated bands. He disliked fellow members of Fletcher Henderson’s Orchestra because of their “lack of musical curiosity” and pompous ways. In 1931, when Memphis police arrested the band in a bus terminal after a white manager’s wife argued about the band’s tour bus rental agreement, he dedicated the song “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead, You Rascal You” to the police department during an intercity radio broadcast.

In 1932 their London engagement was met with criticism indicative of the period. One journalist wrote, “His actual presence gave me a shock” and found “something of the barbaric in his violent stage mannerisms.” The “Daily Express” cited “savage growling is as far removed from English as we speak or sing it” and called the act “as modern as James Joyce.” Another writer described Armstrong as “the ugliest man I have ever seen on stage.”

Some British patrons walked out on the band. Swedish composer Gösta Nystroem was repelled by the “his clean-shaven hippopotamus physiognomy” — all supporting Teachout’s belief pre-World War II Europe was no romantic haven for Jazz Age black musicians. Back home, “Time” referred to Armstrong in 1932 as a “Black Rascal,” saying “no black man works harder.” The article mentioned his marijuana habit, something never referenced in mainstream print again until a 1967 article in which Armstrong (dishonestly) denied usage. Even American songwriter Hoagy Carmichael (“Stardust,” “Georgia On My Mind”) spoke of the “big lips of his” and “cannibalistic sounds.”

Pops stood up to mobster managers, including a minion of Al Capone, but thrived as a crossover artist only after signing with Chicagoan Joe Glaser. Like former wife Lil Hardin, Glaser pushed Armstrong to new heights. In leaving personnel and touring matters to his wife and then Glaser, Armstrong struck an ideal balance between large living and business sense. The formula worked. By the early 1930s, he had recorded with country star Jimmie Rodgers, and his works had been covered by former mentor Joe Oliver, Earl “Fatha” Hines, Jelly Roll Morton, Ethel Waters, the Mills Brothers and Chick Webb. His influence was already audible in the styles of vocalists Bing Crosby and Louis Prima. The author maintains if he had only recorded “Stardust” and “St. Louis Blues,” he would be remembered as the greatest jazz soloist in history.

The author takes us inside the studio to see Armstrong’s recording approach, which generally differed from the freewheeling attitude of his live gigs. He trusted manager Glaser to choose his accompanists and repertoire, some critics believed to a fault. Glaser placed emphasis on populist appeal and catchy tunes.

Armstrong’s sense of humor was reflective of what South Side Chicago, then America, and finally, the world saw on stage. Of marijuana laws, he wrote, “At first you was a mis-do-meanor … But as the years rolled by you lost your misdo and got meaner and meaner … jailhousely speaking.” Pops’ most public pronouncement on race relations came in 1957, when he denounced President Eisenhower as having “no guts” for not ensuring the safe enrollment of the Little Rock Nine into Central High School. He called Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus, who surrounded the segregated school with state National Guardsmen, an “uneducated plowboy” (a term far sanitized from what Armstrong actually told a young reporter who captured Armstrong’s unbridled political ire). So entrenched a cultural figure was he by then, when Ford Motors tried to kick him off its upcoming Edsel (variety) Show, CBS executives backed him. The U.S. State Department continued to send The Louis Armstrong All-Stars on international goodwill tours.

During the peak of Motown and Beatles’ popularity in the U.S., Armstrong recorded the single “Hello Dolly” as a favor to an associate and before the show opened on Broadway. The song was a runaway hit that moved the Beatles down the pop charts a notch, was shipped to the touring All-Stars’ act to memorize for immediate incorporation in their retinue, and became a staple of Pops’ many television appearances for the last seven years of his career. Most important, a new generation of fans identified him with the 1964 single. Teachout reveals the physical limitations a road weary Armstrong faced in his sunset years.

Armstrong lifted hearts with his horn. After labeling him an Uncle Tom for years, Dizzy Gillespie admitted he had misjudged his “absolute refusal to let anything” even “anger of racism” steal his joy or his smile. Pops liked to recount a story of a white Texan who confronted the band when they played in Lubbock, jabbing the trumpeter’s chest with a forefinger declaring, “I don’t like n—‘s.” The sidemen were set to jump the offender, but Armstrong stopped them and asked the man why he didn’t like colored folk. The man couldn’t answer, was moved to tears by his own bias and he and his family became Armstrong’s lifelong friends.

Bijan C. Bayne is a frequent contributor to The Bay State Banner.

——————————

Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, by Terry Teachout, Houghton Mifflin, 496 pp., $30 hardback